Discover more from Never Met a Science

[Drake] is necessarily international. An international thinking does not exist, only the universal thinking, coming from one source. However, if it is to remain close to the origin, it requires a fateful dwelling in a unique home [Heimat] and the unique people [Volk], so that it is not the folkish purpose of thinking and the mere 'expression' of people-: the respective only fateful home of the down-to-earthness is the [Taylor Swift], which alone can enable growth into the universal.

Martin Heidegger, Black Notebooks. Citation from the translation by Yuk Hui in his The Question Concerning Technology in China: An Essay in Cosmotechnics. Drake and Taylor Swift parentheticals my own.

It’s December 2012 and I’ve just finished the first semester of a year teaching English in Santiago, Chile—the loneliest of my life, the inevitable comedown from the social high of undergrad amplified by moving 5,000 miles away, to the most conservative country in Latin America—and I’m visiting my college buddy in his Williamsburg loft.

He’s living the dream. “Staff” “job” at VICE—barely above minimum wage but perks like pizza and beer, ridiculous promos from record labels, and the attention of the fine young woman of North Brooklyn. The loft isn’t a traditional loft, in that it’s actually just the landlord built like a treehouse in the high-cieling’d living room of an apartment, where he lived. The door was a towel and you couldn’t stand up in it.

So we did what any 22 year-old “hipster bros” reunited after a trip to the semiantipodes would do. We got regular-zooted on weed/adderall/Corona caguama and blasted the new Taylor Swift music video, for Trouble. And, for his “job,” blogged about it.

“It is definitely the most important song she has ever released”—we wrote, though I wouldn’t have believed it were it not still on the VICE website. The immediacy of the semiotic experience of Taylor Swift dressing up like a hipster! What a move, in the vibe space. The little EDMy warble that accompanies her autotuned voice in the chorus represents an irreparable break with her past, the way artists in art museum captions “break” with their calcified aesthetic inheritance and strike boldly into the unknown.

“As a bridge-burner, ‘Trouble’ is pretty obvious, especially on an aesthetic level. The thing is essentially an electronic pop song, armed with a tastefully cavernous dubstep drop and all. And with its video, she's offered a slightly more subtle subversion of her image, all the more jarring if you're paying close attention.”

It’s difficult to recreate the hipster Weltanschauung—even for me, in my own memory, let alone in writing for people who never experienced it firsthand—without slipping into parody or pathos. So I’ll play it straight. A lot of it had to do with intellectualizing media, and especially music.1 We were paying close attention.

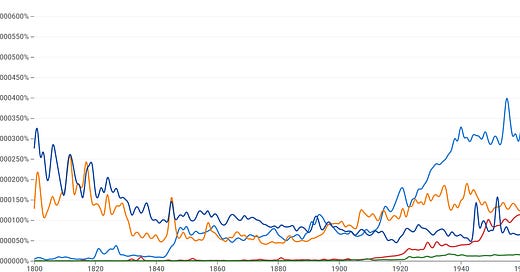

Google searches for “hipster.” Peak period from the fall of Lehman Brothers to the fall of 2016.

We wrote that “Swift’s core group of fans (weirdo poptimist music writers not withstanding) is now probably around the age of 16.” We were kidding ourselves. We were and are in Swift’s core group of fans…born in 1989, the same year as her, and the rest of the Peak Millennials. Poptimism was just our excuse to intellectualize media — crucially, in this case, music that we could talk to girls about.

Poptimism was successful at delegitimizing rockism, but it’s an intellectual fantasy to assign cultural criticism much causal efficacy — especially as the power of music curators, journalists and tastemakers was about to hit a tailspin. Pop music was always going to be fine and rock music was always not going to be fine, but for reasons related to material conditions.

Today, the critical status of poptimism is on the wane. As we survey the wreckage of the media cultural landscape, it seems there was something lost when musicians, critics and audiences started caring less about music being good than being accessible.

Ironically, the biggest beneficiary of poptimism may have been rap music. The critical standing of existing *local* rap music was beyond repute, if not accepted by the masses. The poptimist double move militated for the creation of pop-rap. For the uprooting of the sound from these local rap scenes to something more universally palatable.

That is, the dialectical response to a critical re-evaluation of Taylor Swift was to make Drake possible.

Some pop-rap is really just pop; consider the obligatory 2010s guest verse by Ludacris or Snoop on a Justin Bieber or Katy Perry track. (Or consider…Pit Bull). These songs don’t really have themes, let alone meanings—rather, they presage contemporary Spotify auto-generated vibes to function to.

Drake never participated in this lending of the simulacrum of street cred because he never even pretended to have any to begin with. His origins as a child actor are sometimes mocked but at this point usually ignored—but we cannot consider them incidental. Drake was programmed for mass consumption, for consumption not by people but by the masses. His music was born devoid of the thick network of personal, geographic and sonic relations that defined local rap scenes to date.2

Drake’s “cred” comes from a different source: himself. He foregrounds the personal, confession rather than braggadocio. What makes this relatable, authentic is the fact that, as he tells us repeatedly, Drake sucks. He is petty, unreliable, obsessed with women but not with any particular woman.

I know a lot of girls be thinking, this song is about them. But don’t get it confused. This one for you.

He has one redeeming quality, though: he has a lot of money because he is good at his job and he works really hard. The main theme of Classical Drake is how much time he spends working, how much he has sacrificed, how many personal relationships he has neglected in pursuit of the grind.

He was thus the perfect soundtrack for uprooted Millennial strivers anywhere. Rap Caviar in the airpods in the Uber, all black with the white sneakers and the Away suitcase, whether it’s 9am in Dallas or 5am in Toronto or 6pm in New York or, heaven forbid, 8am in Charlotte.

So two years after Trouble, when Drew and I went to a party at the apartment of a Rap Genius co-founders in one of the soulless new Williamsburg waterfront condos, Drake was everywhere, the soundtrack to our lives. The Rap Genius guy apparently had two of these apartments, connected by a balcony; we stayed in the one without any furniture but with several handles of liquor, playing Drake’s Worst Behavior on repeat and screaming the lyrics until someone kicked us out. Like Drake, we sucked.

Drake lacked the possibility of rootedness; Toronto is one of the world’s great non-places, certainly without a local rap scene to return to and draw from. To supplement the strategy of Millennial self-hating self-aggrandizement, he went international: first to the Carribbean immigrants and then to British grime scenes.3 This is not “street cred” but “passport cred,” Music for Airspace. I guess it really is just me, myself and all my millions.

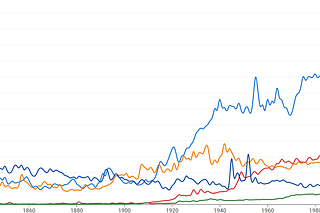

The collapsing of the Millennial dialectic (Taylor Swift in red, Drake in blue).

According to Google Trends, Drake and Taylor Swift were the most popular Millennial musicians of the 2008-2018 period, with a back-and-forth battle with each new album release. After the fallow Covid period for both, Taylor Swift has emerged as the most famous person on the planet — while Drake’s last gasp of relevance came from leaking a dick pic on Twitter.

In a self-seriously highbrow article about pop music, we’re going to need to talk about capitalism. Given the set-up, I might argue that one of them is the perfect vessel for capitalism (bad) but that the other has some redeeming authentic or idk revolutionary characteristic that means while yes they participate in a capitalist economy, they (and their fans) are good.

But no. Drake and Taylor Swift are both perfect vessels for capital, which is in fact the unstoppable source of all your problems. But vulgar anti-capitalist broadsides are a dime a dozen on this website; we need to be more precise.

The genius of capital is not that it always automatically makes things worse in the ways that you already know about — but that it is infinitely malleable, that it changes, that human efforts to create pockets of existence outside of capital are rapidly forced to grapple with everything that already exists.

Drake is globalist, neoliberal capitalism. Drake is the brief lacuna after the end of history. Drake is authentically empty, the apotheosis of the internationalist modernity that Heidegger so vividly fights back against.4

His songs are effective through unrelatability, through the mockery of the very possibility of relatability. The ideal Drakean subject knows that they themselves lack subjectivity and wants to be reassured that everyone else does, too. Through Drake we recognize ourselves in The Other because we’re both just mirrors, me’s (and you’s) en abyme.

That’s why every song sounded like Drake featurin’ Drake.

Drake is neoliberal; Taylor Swift is what comes next.

Taylor Swift is post-liberal.

Taylor Swift is post-historical.

Taylor Swift is post-authentic.

The task of the critic is to figure out more specific terms for Taylor Swift rather than these placeholders, meaty concepts that carve up the present rather than merely noting that we're no longer in the past. Flusser’s concepts of the “technical image” and the apparatus-operator complex are the best I’ve got for now. But contemporary music — and music criticism — may prove generative.

Hyperpop acts like 100 Gecs defy the concept of genre as locally and historically embedded. Ska, nu-metal, screamo and techno each evolved in a specific time and place, in response to social and technological change and in conversation with music that came before. In hyperpop, these genres become merely sounds, ripped from their context. This is the death of scenes recently described by Mireille Silcoff.

The Eras Tour is a hyperpop hyperobject.

Taylor Swift’s genius is to create subjective histories, to re-inscribe herself within the life cycle of each of her listeners. Even as our objective histories and grand narratives of civilizational progress become absurd, we still each of us have a life cycle.

A historical Era transcends the individual, situating them within much larger forces. The post-historical Era is personal periodization without progress, a list of TikTok trends in which we participated.

Swiftian relatability begins where Drake left off, accepting the premise that listeners do not possess stable and well-developed selves and giving them narratives with which to construct those selves. Her fans find her so intensely relatable because they are relating to themselves, selves which have been constructed from Taylor Swift songs.

Famously, Taylor Swift’s songs are distinguished from other pop superstars’ in that she actually writes them. They are intensely personal, based on her lived experiences. But the obvious paradox is that she’s been a superstar for fifteen years; she does not have experiences that anyone else can relate to. So what she’s really describing in her songs are the lived experiences of everyone else, filtered through media she herself consumes — and directly from her audience.

I’m not so naive as to let my whole take hang on whether Taylor Swift “really believes” her songs. Foucauldian discourse analysis tells us that the identity of the speaker of sentences is less important than the structure which makes those sentences possible. And Taylor Swift’s key insight is to be hyper-focused on her audience. The fandom she has been cultivating has never been unidirectional (One-Directional?) — she’s not just doing fan service, she’s figuring out what they’re missing. What moves to make in the semiotic vibe-space.

This is why it has taken fifteen years for Taylor Swift to really hit: she and her audience have been mutually constructing their own subjective history, their own Eras.

Nazism, Italian Fascism, the right wing of the Kyoto School—and today, Duginism in Russia—these are the bad faith attempts to overcome modernity by retreating into the magical pre-modern of their respective ethnostate while simultaneously using modern technology to kill or subjugate everybody else.

And say what you will about Taylor Swift, that is not her intention.

But it’s also not even an option. The aspiring American post-liberal metaphysical fascist is hamstrung by the lack of a coherent ethnic national identity to which to appeal. Our ethos is progress, pure and simple, as Margaret Mead diagnoses. So the heart of our metaphysical crisis is the contradiction of post-historical progress. Flusser writes that

Nowadays ‘to progress’ does not mean to demand the future, but to avoid the past...our progress is a method to avoid being devoured by the past that chases us

All of which is to say….

Drake fell off. We needed that. But where, where does that leave us at?

In this way, at least, I think my past self would be proud of me: I figured out a way to intellectualize media professionally.

To be fair, Kayne did all of this first.

One problem with this approach is that no one really liked it.

To be clear…just because Heidegger’s critique is “vivid” doesn’t mean that it’s good. The challenge for thinkers aspiring to overcome modernity is to avoid the bad faith retreat into what Flusser describes as Romanticism and Yuk Hui as “metaphysical fascism.” Zizek provides detailed context for Heidegger’s antisemitism and how it is mistaken even within the terms of his own philosophy. Basically, I’m really not making anything out of the fact that Drake is half-Jewish, but it seemed even worse not to mention it at all.

Subscribe to Never Met a Science

Political Communication, Social Science Methodology, and how the internet intersects each

This is an interesting take. I buy some of it. Drake is an unrooted, expensive "floating tree" in a posh hotel where you don't know what city you're in because "luxury" is the hotel's ethos. Taylor Swift is more of a sprawling big oak tree in the center of one of those luxury hotels that is in every city, but they keep the "theme" of Americana/that city intact in their design. Sure they uprooted the tree (or maybe their whole thing is they built the hotel around the tree and couldn't knock it down per ordinance!), but it the feeling of the city can still be felt with in the structure.

Technological advances, I think, make us want to have a future based off the past. Nostalgia acts provide us a place to put our baggage while we roam and look at new acts inspired by these artists, like 100 gecs (who I enjoy in addition to Drake and Taylor), but we always return to the hotel lobby when we feel frightened by the lack of groundedness of so many acts.

We had the show (2000s/early 2010s), we had the after-party (late 2010s/never-ending), and now we're in a hotel lobby that is so grand and luxurious. Everyone knows at 4am you have to leave the lobby and take it to your room, and do what you like. I'm going to sleep. (obviously, noted the person who I borrowed these lyrics from in the last bit is awful)