Discover more from Never Met a Science

One great thing about finalizing a book is that you immediately encounter a ton of relevant material you wish you’d read years ago. In related news, my book is finished! And can be pre-ordered on Barnesandnoble.com and other websites. The book expands on much of what I write about on this blog, particularly the interaction between the rapid changes occasioned by tech and the social institutions that operate on a much longer time scale.

tl;dr: For many unrelated reasons, the United States is demographically top-heavy during the most important media technology revolution in the history of humanity…and that’s bad.

The book is chock-full of novel quantitative descriptive data, survey experiments and institutional analysis, but one thing that’s missing, that I only now came to appreciate, is the distinctly American flavor of the cultural tension produced by these trends.

American culture is famously dynamic, optimistic, youth-oriented. It is here that the Protestant work ethic combined with boundless frontier to produce the confident, inventive, frank go-getter who so fascinated European observers from de Tocqueville to Nabokov.

Talking in these terms is out of fashion; the idea of a national “culture” as a coherent or useful analytical construct feels essentialist, unserious.

My inspiration for this line of inquiry is Margaret Mead’s 1942 book And Keep Your Powder Dry, which I picked up on a whim at a massive library sale in State College. Mead is a legendary anthropologist and one of the 20th century’s most adventurous lovers. Like most old-school anthropologists, her most famous work involves the study of The Other in the form of isolated or distinctive “tribes” or indigenous communities. Recently, anthropology has embraced the study of the anthropologist’s own culture, but this was highly unusual in the 1940s.

Mead’s thesis is that the “success creed” is the “moral keystone” to the American character: “The insistence upon a relationship between what we do and what we get is one of our most distinguishing characteristics. On it is based our specific brand of democracy.”

How can we know if there’s any truth here? In anthropological terms, of course, Mead can be correct (or incorrect) that she has identified a defining American myth, that these are indeed the stories we tell ourselves. But how might we know if anyone believes them, if they have any effect in the world?

To justify Mead’s approach—indeed, to justify any social scientific project—I believe in the necessity of prediction. So the uncanny accuracy with which she predicts Trumpism seventy-four years in advance should give us pause before we dismiss her broad-strokes cultural analysis outright. My jaw dropped when I read this passage:

It is this cynicism which could well form the basis for American fascism, a fascism bowing down before any character strong enough and amoral enough to get away with it, to get his....There are very few Americans who can identify with Hitler in his cold destructiveness, but they can identify with his success in getting away with it, in the way in which he has made monkeys of his opponents. The belief that all of life is a racket and the strongest racketeer gets the loot is the bastard brother of the belief that life is real and life is earnest...it stands as a terrible warning of what may come from any concerted attack on our success creed...

Mead's project in this book is odd. As an anthropologist, her task is to describe the functioning of cultural systems to illuminate something about the human condition, but the introduction to the book explains a special urgency: the US had just entered WWII, and she explicitly intends this book as her contribution to the war effort.

At the time, there seems to have been some fatalism about the warmaking efficiency of fascism, that the unity created by brutal elimination of difference rendered the Nazis unbeatable by nations allowing human freedom. Mead argues that copying fascist methods here would not just be morally wrong; the American character simply would not take to German-style fascism, we're too individualistic. Instead, our best strategy is to fight and win the war in a way that harnesses our cultural strengths. Hence the unusual decision to turn her anthropological gaze inwards.

Two other pieces of historical / intellectual context:

Mead’s thinking is implicitly Freudian, like many intellectuals of her era. Reading social science from the 1940s to 1960s, I’ve been struck by how everyone takes basic Freudian logic for granted, and how alien that feels today. Mead’s focus on the relationship between parents and children (and primarily between fathers and sons) provides a useful angle on generational conflict, even if she takes it too far at times.

Relatedly, Mead thinks that the aftermath of WWI and then the Great Depression were a terrible one-two punch to the American psyche. We "won" WWI, she thinks, but we lacked follow-through, retreating into isolationism and leaving a festering discontent that enabled Nazism. The Depression hit closer to home, ruining an entire generation by denying them access to the dynamism and progress that defines American self-worth. None of this is shocking to the modern reader, but Mead's description of the ubiquity and intensity of the psychic turmoil of the Depression is noteworthy.

"A whole generation of fathers have faced their growing children with bowed heads because they had somehow failed; a whole generation of children have grown up under the shadow of that failure, believing in many cases that someone--the Federal Government, or somebody--should do something about it."

The nexus of class, economic progress and generational identity can be difficult to disentangle. One premise of my book is that the Baby Boomers are an unprecedentedly large, powerful, wealthy and long-lived generation. This is contrary to “the American Dream” that children can grow up to live better lives than their parents. But it also conflicts with the idea of class as a static characteristic inherited from one’s parents.

There is some conceptual slippage here. Most thinking about class comes from Europe, and the frame has generally been a poor fit for the American cultural mythos. (Regardless of whether the immortal science of dialectical materialism is in fact externally valid when generalized from the 19th-century European context, this cultural mismatch explains some of why it never really took off here.) Instead, Mead describes the American class system as fundamentally dynamic; it breaks down when "we still demand of every child a measure of success which is actually less and less possible for him to attain."

A number of conditions made this dynamism possible. First was “the existence of a frontier and expanding economy” so that the pie really was growing. More subtle, though, has been the increased rigidity and legibility of success. Where once men could achieve success in a wide array of incommensurate fields, by 1940 “the symbols of success were so definite and so clear--measured in houses and motor-cars and fur coats and expensive college educations--that it is impossible to shift them with a shifting economic system.”

These markers of success have only grown in importance (you thought Columbia was expensive in 1940??), leaving fewer opportunities for new generations to forge their own definitions of success. We live in the long Boomer Present, a period of prosperity but also of stagnation both cultural and economic.

The internet has created a new frontier, open spaces where new social structures can be created without the knowledge or permission of the old. This is, per Mead’s framework, how America is meant to work: progress prevents decadence, new technologies allow for mobility at both the individual and societal level. The coder and the influencer are updates of classic American archetypes, people with the skills to meaningfully change their environment, to build something new, without the need to work their way through some guild or other hidebound institution.

You might think that this digital frontier is either intrinsically incapable of becoming more than a pale shadow of “meatspace,” or you might think that the actually-existing internet is already hopelessly enclosed by powerful corporations; I think both. But the Millennial/Gen Z desire for something new, a sphere of activity not currently dominated by the same cohort of Boomers who have been in control for decades, is both powerful and largely unrequited.

Boomer cultural power has prevented these new forms from achieving legitimacy. Anti-Boomer resentment as manifested in the “OK, Boomer” meme is derived from precisely these two dimensions: the inability of Boomers to understand the internet, and the condescension of Boomers who think that younger generations have it easy.

Daniel Markovits’ recent book The Meritocracy Trap explains the crushing pressure produced by the decline of economic growth and the increasing importance of a rigid system for legitimating success. “Meritocracy” was originally a British critique of the modern British class system, but the arthritic joints of our cultural institutions have allowed the critique to catch up to us. Mead is again prescient in her diagnosis of our contemporary malaise, what happens when the “success creed” cannot be upheld:

"If we demand a man must succeed to be regarded as good, how difficult do we dare to make that success without running the risk of breaking the hearts and minds of the many who fail?"

Returning to technological progress—the whole world has become much more American, in this sense, but technological dynamism remains central to our culture. Technological innovations inevitably produces intergenerational conflicts that must be resolved differently than they are in more static cultures:

“In America, with the rapid rate of change, most parents know that the child will not do what the parent did, but something different...He must applaud in his son something which he did not do himself, something which he has no way of judging.”

If a culture elevates the best competitive athlete (a longstanding tradition in the Americas, as Graeber and Wengrow document in their recent book), there is no shame in the children eclipsing the parents as they age; this is as natural as the seasons.

The freedom of children to find their way in the new world, however, serves as a reminder to the parents that this new world is not for them. This is not the natural replacement of waning old bodies with the vigor of youth, but rather “the dishonorable gulf which results from the parents getting out of date.” Americans don’t simply get old; they become irrelevant, exiles in their own society simply by staying in place. The chain emails and inane Facebook memes that have come to represent Boomer technological incompetence have always been with us; Mead notes that “the children are fast outstripping the parents, and handling daylight savings time with no mistakes at all while the parents are still missing trains.”

The incommensurability of youthful achievements with the feats of previous generations equally causes a sense of dislocation for new generations. We are denied the satisfaction of maturity that comes with beating older generations at their own game because we are not playing the same game. As a Freudian, Mead describes this in Oedipal terms (the son must kill the father to take his place in the social order), but the language of corporate advancement is more familiar today. Consider the senior people in your profession. How do you measure up against them when they were your age? In most cases (academia very much included), the comparison doesn’t even make sense; their world is so unlike ours that the we may never be able to beat them.

This produces a pathology that I find especially common among Millennials and Gen Z: identification with generation itself, making birth cohort and the specific technology/pop culture of one’s youth into a central facet of identity. The shared experiences of youth remain fixed even as the world progresses. Same as it ever was!

“Only those who have made a point of pride out of the very pace of our lives, out of the very fact that those born in 1920 start off wiser than those born in 1910, can find pride in such a circumstance.”

As a final validation of the predictive effectiveness of Mead’s approach, consider what is literally the most important thing in the world: misinformation.

Constant change is a source of anxiety. Parents—even successful parents—who want their children to succeed cannot simply initiate them into the American way of life, cannot replicate their own childhoods. They must instead always ask “how can I bring my child up to be successful in an unknown 1962?” There is no ultimate authority; we must go instead to “prophets and seers, which means incidentally a good many calls on quacks and charlatans, without the test of time to sift out one from the other.”

Most new ideas are bad; most innovation ends in failure. A genuinely conservative epistemology, based on respect for traditions refined over generations, is incompatible with American culture. Perhaps this is why true conservatism has no constituency in the US. We get plenty of reactionary nostalgia, especially in this Böomerdämmerung, but the impulse to RETVRN to a tradition constructed by Madison Avenue in the 1950s is transparently pathetic.

But that’s where we are, now. I call this unprecedented concentrated of demographic, social, cultural, economic and political power within a single generation nearing the end of its lifespan Boomer Ballast.

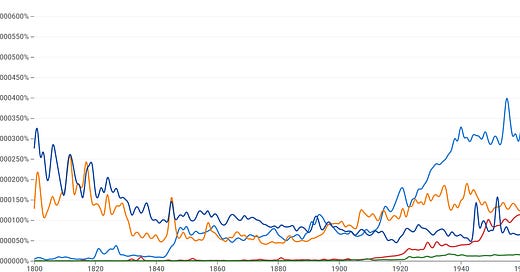

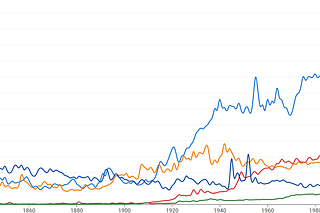

Auguste Comte famously connected the rate of generational replacement to the tempo of social progress; to lengthen the lifespan of the individual would mean slowing up the tempo of progress, “because the restrictive, conservative, ‘go-slow’ influence of the older generation would operate for a longer time.”

Mead’s argument explains why Boomer Ballast is especially wrenching in the United States. Nowhere else in the world reacts so poorly to an explosion of restrictive, go-slow influence.

And the converse is also true: our culture has little use for the old. We have long simply wished that they would go away. Today’s Boomers are alienated but very much alive. They’re too old to partake in the American tradition of progress. The blessing of longevity and wealth that this progress created includes the seed of a curse as ironic as any devised by Hades.

The Boomers will be alive for decades. Modern communication technology provide them a crystal-clear vision of the world they built being usurped by younger generations. Cynical media and political entrepreneurs will continue to terrify and extort them. The American success creed is not designed for a generation holding their grip on power into their 80s. Forward progress is impossible; they can only hope to slow their own decline.

Mead provides a prescient summary of Boomer politics: “In public life, this is a group that feels insecure and exposed. Any change may be directed against them....[this] viewpoint [is] more congenial to those who have retired than those who still feel that they are on the move.”

My goal with the book is analogous to Mead’s: we face a serious challenge in learning to cope with the shock of the internet and social media, and our response must take careful account of what we have to work with.

For most of the 21st century, Boomer Ballast has produced a false sense of continuity with the past. The contingent and ephemeral culture and social forms of the decades after WWII have persisted for an unnaturally long time (recall the ubiquity of a recent documentary about a documentary about a the recording of a Beatles album), and given demographic trends, they are likely to persist until the early 2030s.

And that’s when things are going to get weird. There will be no father to kill, no conflict, only a mess of confusion. Everything my generation was raised taking for granted will be up for grabs. Mead’s final piece of advice, then, is to avoid the American of weakness to want to build the world new, to tear everything down and start from scratch. The success creed is failing but remains widespread; we can neither retain it as is nor pretend it doesn’t exist. We need to figure out how to use the internet to build post-Boomer America.