Boomer Ballast

and the inevitability of intergenerational conflict

Over the past 250 years, the United States has enjoyed an unusual degree of political continuity. And over the past seventy-five years, since the end of World War II, that continuity has anchored itself in a single generation, a source of immense demographic gravity: the Baby Boomers.

The collective experience of Americans alive today is one of stability. We have lived relatively calmly amidst the rise and fall of empires, bloody civil wars, explosive economic growth, and accelerated technological progress. And we have grown convinced of our own inevitability, especially of the specific norms and institutions that the Boomers created.

The 2016 presidential election was a shock to this system, but the system rapidly re-asserted itself. The spectacle of the two oldest presidential candidates in history playing out on revolutionary new communication technology illustrates a central tension in the United States today.

It feels like the time has come for the twilight of the Boomers. The American Dream is no longer true in the way it was for more than a hundred years: the average Millennial will earn less money than their parents. Generational legitimacy through progress has faltered. Young people are making their own worlds with smartphones and the internet, less and less connected to the old world. Postwar political politesse is evaporating. The reputations of once-revered institutions—everything from the university to the Supreme Court—are crumbling. Even the pantheon of the American Civil Religion is beginning to crack. It feels like the cusp of a revolution, a new world waiting to be born.

And yet. Boomers still control both major political parties, the center of electoral power, all of the major institutions (except tech companies), the mass media, the majority of wealth, and huge amounts of land. Far from going away, the power of the Boomers will increase over the next five years, as more of them retire and spend more time and energy participating in electoral politics and consuming culture and media. At the earliest, Boomer power will peak sometime in the late 2020s.

I call this phenomenon “Boomer Ballast.” I explore it in much more detail in my forthcoming book — and here’s a preview.

Ballast

Unless you have recently travelled via sailboat or hot air balloon, the word “ballast” may be unfamiliar. These vessels both float, and ballast refers to the excess weight they carry to prevent them from being too easily driven off course or capsized by the air or water currents that drive them forward. This is a balancing act; too much ballast and they sink like a stone, but too little and they cannot be controlled.

Most single-person vehicles today have little need of ballast. A car, for example, usually sits solidly on the ground; it moves forward by an internal motor, rather than needing to harness the uncertain elements for propulsion. Power steering gives the driver precise control over the direction the car goes, and our eyes can easily and immediately track the effect of turning the steering wheel.

Unfortunately, running a large, complex institution like a nation state is more like sailing a boat than driving a car. The cliché of referring to the “ship of state” is not a coincidence; in fact, the etymology of English word govern is derived from the Latin word term gubinare, which was used to refer to both the action of steering a ship and governing a polity.

Unlike a precise motorist, the steersman can only hope to keep the ship pointed in the right direction, adjusting to ever-changing conditions and unknown currents. When a new situation arises, the state can respond by implementing new policies, but it is almost impossible to know the effect of those policies in much detail.

It would be silly to say that “ballast” is intrinsically helpful or harmful. Ballast keeps the ship stable and makes it slower, less responsive; stability and speed are two sides of the same coin. Traditional societies where nothing ever changes, where innovation is crushed underneath the weight of the past, eventually either implode or face destruction by more dynamic societies; too much ballast is a problem. Radical societies where nothing is taken for granted and the rules change overnight tend to fragment into smaller pockets of stability or descend into chaos; too little ballast is a problem.

Most debates about politics are over what kinds of policies the government should adopt. Which direction should we steer the ship of state? The wonky, technocratic mood that attends these policy debates can sometimes give the impression that governing is simply a navigational problem, one that can be solved with better engineering. Given that policymakers really do need to make decisions, this style of analysis serves a valuable purpose.

The problem is that the ship of state is not at all fixed. Nations, societies, are made up of individual people, each of whom is unique but all of whom follow the same arc from infancy to old age. The ship of state is the Ship of Theseus (the Greek myth in which every individual plank is gradually replaced), and the task of government is to steer this protean vessel, always adjusting to both the changing environment and the shifting composition of the ship itself.

Boomer Ballast

Steering is immeasurably more difficult if the steersman is unaware how the ship is changing, or even that it is changing at all. Thus the aim of this project: to establish that the Baby Boomer generation is today more powerful than any previous generation at this point in their life cycle, and to trace out the implications of this Boomer Ballast for the next decade of American politics and culture.

The first half of the argument entails describing the various historical trends that have combined to produce Boomer Ballast. Most important is demography, the actual distribution of human beings in a society. I will use two distinct demographic lenses. The first is the age pyramid, the raw distribution of the ages of people in the United States. We are older than ever before, and getting older. The second demographic lens is cohort or generation, the way that people born in the same range of years have similar experiences, preferences and beliefs.

In a given time period, the distinct effects of age and cohort are impossible to tease apart. I will argue that the Baby Boomers are important for understanding the recent past and near future, sometimes because of their experiences and proclivities as Boomers, sometimes as people late in the life cycle. It would be more satisfying if I could analytically separate these two types of causes and estimate the relative magnitudes of their effects; unfortunately, this is statistically impossible with the data that exist.

Regardless, the combined effect of these two causes is Boomer Ballast, the unprecedented concentration of raw demography, wealth, cultural relevance, and accumulated historical experience in a single generation at the top of the age distribution. Our “ship of state” thus has more ballast than ever before, rendering us unusually stable and thus slow to adapt.

The effects of Boomer Ballast are not uniform. How they play out in each sector of society depends on the institutional setup of that sector, and in particular, the rigidity or flexibility of those institutions. Generally, the more rigid institutions will see longer periods of Boomer dominance and a struggle for younger generations to make headway. This is the case in electoral politics in the United States, where each of the two major parties are still controlled by Boomers and no youth-oriented third party is viable. The sectors with more flexible institutions, like media and culture, will still see older institutions run by Boomers, but new information technology will allow younger generations to begin building their own institutions that can grow in prominence as the legacy companies fade into irrelevance. I examine this process with respect to cable news and upstart youth media centered on YouTube.

The second half of my argument takes these descriptive facts and explores what might be done with them. The key question facing American politics in the 2020s is whether the growing demographic, cultural and economic power of younger generations can be effectively mobilized to apply pressure to the political system and have their preferences represented. The mechanism by which this could happen is what I call cohort consciousness: a sense of shared identity and purpose among Millennials and Gen Z. I then present novel survey experimental evidence that indeed younger generations seem to have a sense of shared identity, and they are willing to take political actions to advance a common agenda.

Again, the central obstacle to seeing this agenda represented in national political discussions is the iron grip of the two-party system. When younger generations succeed in shaping one of these two parties, however, we should expect to see the central political cleavage shift to the zero-sum competition over federal budget priorities. Younger generations report the most important issues facing their generation as student loan debt, housing prices, and climate change; Boomers are worried about Medicare, pensions and Social Security. A looming budget crunch caused by demographic shifts threatens the funding structure of these Boomer issues, and when it arrives, the decision to either bail them out or address student loan debt and climate change will be a pivotal political issue.

Why we need “Boomer Ballast”

A central novelty that will be with us throughout the 2020s and into the 2030s, is the elderly American, the Baby Boomer. There are tens of millions of them—alive, alienated, and active.

They are alive because of the progress they helped bring about. Life expectancies have been extending for centuries, including life expectancy conditional on reaching old age. The fruits of this progress coincide with the aging Baby Boom. The age distribution of the United States is top-heavy and getting heavier: in terms of either absolute numbers or percentage of the adult population, the peak concentration of retirees will occur sometime in the late 2020s. This fact is difficult to fit into any of the dominant models of politics or economics. Communists and capitalists alike think in terms of economic structures, not age demographics. The ideologues who dominate the discourse have ignored the issue. But our age transformation is inevitable. The nation has simply never had to think about this many people over the age of eighty before. Today, they represent a growing proportion of the population—and an even faster-growing proportion of voters.

They are alienated by design. In other times or other cultures, elders receive a degree of deference or respect for their role in ensuring familial cohesion and for the wisdom of their accumulated experience. But old people are bad for progress, and progress is the dominant model of liberal capitalism. Declining mental and physical plasticity throughout the life cycle makes the elderly less useful as workers. The cold logic of the market that equates value with productivity does not valorize the elderly.

Older people are also less likely to change their minds. When the world changes, they’re left behind. On topics from gay marriage to marijuana legalization, the Baby Boomers have been routed. The very existence of the elderly serves as proof of progress’s limits: no matter how quickly the views of younger generations change, older generations stubbornly keep median public opinion in place. Indeed, the dominant perspective of many young activists is that they wish Boomers would just go away.

But the Baby Boomers will not go away. Far from it. They are the most active elderly generation in history, and they dominate the economic, cultural, and political spheres like never before. They reaped the benefits of decades of broad-based economic growth, and now they own a shocking amount of the nation’s wealth and housing stock. This gives them a baseline of stability, free time and disposable income with which to influence the other spheres.

The media institutions from the broadcast era of communication technology, the middle eighty years of the past century, are increasingly attuned to the preferences of this powerful consumer bloc. Cable news has experienced a renaissance even though almost nobody under forty watches it. In an atomized era, when physical sociality has collapsed, identities are increasingly formed through overlapping media consumption habits (compounded by Covid-19). The fact that Millennials and Gen Z can create their own media---by, for and about other young people---implies a degree of intergenerational polarization that was impossible under the limited media choices of the broadcast era.

This polarization might be constrained to media-informed intergenerational sniping (“Millennials are killing the diamond engagement ring industry!”; “OK, Boomer”) if the economic pie had continued to grow at the rate it did when Boomers were entering the work force. But declining economic fortunes mean that conflict between the young and the old for financial resources is inevitable. In fact, it has already begun, as Millennials push for student loan debt forgiveness and green energy policies while Boomers nearing or past retirement insist on bailing out Social Security and pensions. This conflict will only accelerate as younger generations question the Boomers’ place at the top of our social and political order.

These are not questions that can be easily asked, the long-standing “third rail” of politics. To question the Boomers is to raise the specter of Death Panels, the conspiracy theory from the early 2010s that President Obama’s Affordable Care Act would ration healthcare among the elderly. The political asymmetry that produced this issue is not a coincidence. Conservative broadcast media is targeted directly at the elderly. While it is unavoidable and in fact desirable that all sectors of society have their interests reflected in media, this relationship has often turned predatory. The primary strategy is to terrorize, to reinforce fears of national decline, especially potent in the contemporary climate.

But it was not until the internet and social media permeated society that elderly politics became the force that it is today. The internet and social media have democratized the capacity to create media. This term democratize has a few meanings. It is generally used to mean “make accessible to everyone,” which is true in this case. But media has been transformed—overnight, in generational terms—from an aristocracy to a democracy, with all the messiness that comes with it.

The democratic mass internet has not had time to create healthy institutions or norms. The aging, powerful Baby Boomers are far from technologically savvy. The supercharged capitalism of online media has rapidly discovered their information-verification weaknesses, exploiting them for attention and cash, and degrading the overall quality of the major internet platforms. Facebook has become unusable for many purposes, and public behavior on the platform is dominated by cruel, inane, and hyperpartisan content designed to prey on the elderly. Most pernicious, perhaps, has been the feedback loop between social networks and the cable news channels that still dominate Boomers’ attention; the former have revealed a tolerance and even demand for more and more extreme political content.

The political media ecosystem favored by Boomers is especially important for the democratic process because of the serious gap in voter turnout between the young and old. The situation among the political donors who play an outsized role in selecting candidates and influencing their platforms is even more extreme. The AARP’s publication remains the nation’s highest circulation magazine; the political focus of this media giant is to prevent even the faintest mention of reforming Social Security. This means that younger generations are inevitably left holding the bag.

Nowhere is the contemporary gerontocracy more obvious than in the elected officials in Washington. In 2014, we broke the record for the oldest Congress in American history. We broke that new record in 2016. And then again in 2018. And yet again in 2020, when the majority of the incumbents who lost election were replaced by someone older than they were. In 2016, at age 70, Donald Trump became the oldest president ever elected. In 2020, at 78, Joe Biden shattered his record.

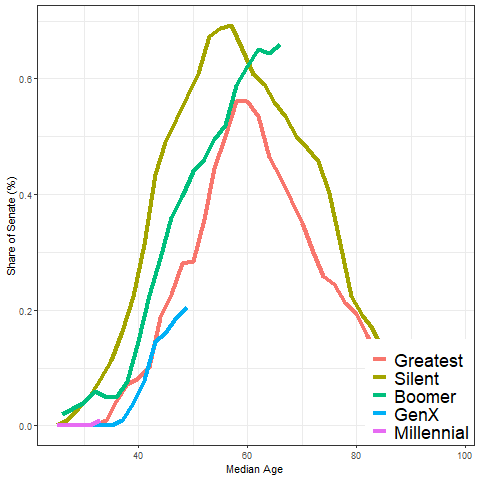

The percentage of Boomers in the Senate is currently *rising*, at a later age than for any previous generation. Gen X and Millennials will never catch up.

Gerontocracies have some merit; people who have had more time to accumulate wisdom and social capital are good candidates for directing a nation based on experience. Although increased life expectancy has changed this dynamic somewhat, one basic idea behind giving Supreme Court Justices lifetime appoints is that the legal system is an area in which we prioritize the accumulated knowledge of the elderly over the dynamism of the young. But our electoral system amplifies the power of Boomer Ballast by rewarding seniority among sitting Members of Congress and high incumbency rates. This system makes the most sense in societies that are generally stable, where the past is likely to be similar to the future, so that the experience of old people can be directly applied to the present.

The United States is at its most gerontocratic while the world is in upheaval, amid the most important revolution in the history of communication technology. Donald Trump blazed an unprecedented path as a politician because---I am mostly serious about this---he was the only Boomer who understood how to use social media.

Ironies and contradictions abound in any discussion of the generational politics of the 2020s.

The Boomers enter retirement at the height of their political and economic power, just in time to see the younger generations disparage their accomplishments.

Our culture fetishizes youth, but new communication technology has given a last burst of relevance to the elderly— at a cost. The digital world is overloading their analog psychic defenses with a neverending parade of political crises recommended by trusted friends and family.

For decades, the dream job to which more children aspired than any other was “astronaut.” Today, according to a recent survey of 8- to 12-year-olds, it is “Vlogger/YouTuber.”

But while the children will never remember the past, Boomer Ballast is reflected in the scope of the political imagination. Remember that before the marketers decided on the term “Millennials,” they called us “Echo Boomers”: we are literally living in the past, fighting over which imagined future to pursue.

The Millennial exceptions prove the rule. The exceptional Millennial politician is undisputedly Congresswoman Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez, a woman of color who can inhabit online spaces with a fluency that cannot be faked. As the identities that have long been central to the construction of the white American subject—geography, extended family, religion, bowling-club member—fade away, subtly demarcated internet habits become the relevant symbol of group identification.

Internet culture enhances the phenomenon of generational identification. The labels imposed by demographers and embraced by marketers have been increasingly internalized by the people they describe. These shared labels make generational politics possible, powered by this sense of membership in a group, what I will call “cohort consciousness.”

This post draws heavily on portions of the introductory chapter of my forthcoming book, Generation Gap: Why the Baby Boomers (Still!) Dominate American Politics and Culture, out May 2022 with Columbia University Press.