Data is the New Oil...And We're the Dinosaurs

Explosive growth can only come from cheating, from discovering some way to break the rules. Most of the time this involves actual explosions.

Because the most important rule is the First Law of Thermodynamics, the conservation of energy.

The jump to modern humans was made possible by fire, by externalizing the energy required to break down food to the energy stored up in wood and rapidly consumed by fire. Further growth was made possible by tapping into energy from animals (oxen for ploughing, horses for riding), wind (for sailing ships) and water (for mills), but this growth was not explosive. There’s only so much wind, so many rivers — and traditional horse power scales linearly in the number of horses involved.

Wood is only so dense. But thankfully (?) for us, wood and other organic material had been accumulating and being buried under intense pressure for billions of years.

Fossil fuels enabled explosive growth by allowing us to cheat the First Law of Thermodynamics. Burning fossil fuels means stealing energy from the past.

Coal was an essential catalyst for the Industrial Revolution. Humans probably would’ve continued to make technological progress by accumulating knowledge and refining our social institutions, but without coal, it would’ve been an Industrial SteadyProgression.

The Transportation Revolution is somewhat less remarked upon but no less important for the daily lives of Americans. The total distance travelled in a given person’s life in 1850 was sharply constrained by energy; it was extremely difficult to sustain speeds over 10 miles per hour. Coal could power ships and trains, but almost no one travelled on these very frequently.

Oil, a much denser and cleaner1 fuel, enabled the explosive growth of the Transportation Revolution. The total number of miles travelled by car, bus and airplane is astonishing by historical standards. And it was only possible once we figured out how to steal energy from the past.

Today’s explosive growth, what we might end up calling the “AI Revolution,” was also made possible by cheating. But this time, it wasn’t energy but knowledge that we figured out how to exploit. Knowledge that had been accumulating in media objects over generations of human communication. Fossil Knowledge.

Data is the new oil, and we’re the dinosaurs. (And yes — this leads to an argument for why we should ban TikTok, let me cook.)

Modern AI, driven by neural networks, has made explosive progress simply by combining more data with more compute. The “scaling question” has thus far been answered in the affirmative: we continue to see improved performance by throwing these two ingredients into the bonfire. Moore’s Law had allowed for continued exponential growth in the former, but it has come at a significant cost. Microchip hardware advances have become more and more expensive, requiring more and more specialization. This specialized capital cannot easily be repurposed. There’s no guarantee that this will keep going, but let’s assume it will. The data is the more questionable input.

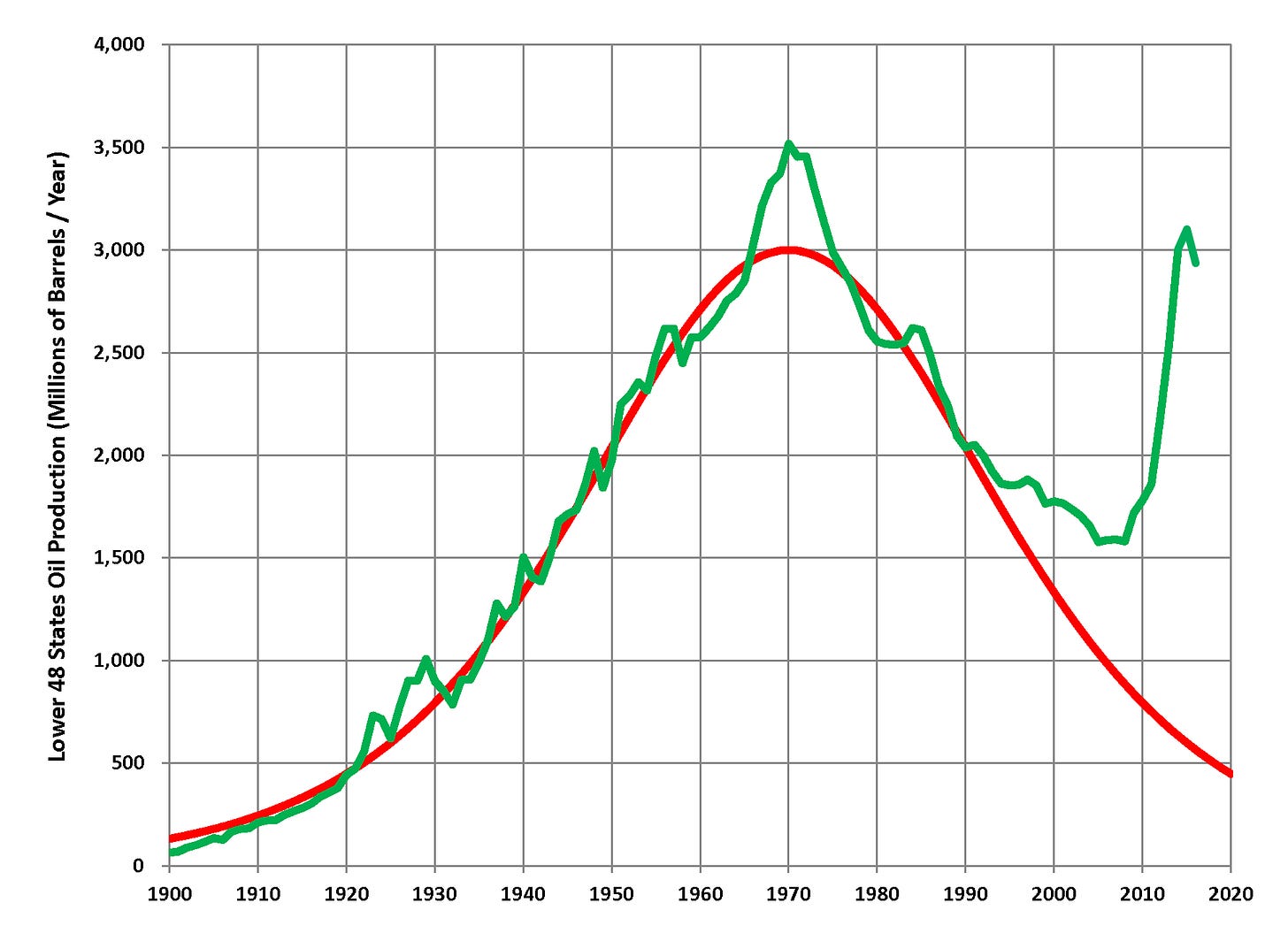

For this fossil fuel analogy to work, it’s important to learn the lessons of Peak Oil. In the 2000s, I remember a lot of anti-capitalist/environmentalist types pushing this message: given a fixed amount of oil in the ground, it must mathematically be the case that one day we will reach Peak Oil production, after which point oil production will of course decrease. The idea was that fossil-fuel driven growth couldn’t last forever and that we needed to start looking for alternatives.

On the other hand, libertarian-economist types argued that supply is more elastic than we tend to think: falling oil production would incentivize people and capital to figure out new ways to drill or process oil.

It was looking good for the Peak Oil camp in the 2000s…and which point this happened. (Red is Hubert’s 1956 prediction, green is actual US oil production).

So how is the data problem for AI different than the Peak Oil argument?

The latter springs from the arrogance of anthropocentrism. The Earth is simply much bigger and older than we can comprehend. A hundred years simply isn’t enough time for us to exhaust the energy stored in our planet by billions of years of biological life. This isn’t to say that everything will always be fine and the miracle of the market will save us from thinking about ecological problems — but that just like in the case of the “population bomb” of the 1960s, we need to avoid normative arguments that are based on falsifiable technological premises.

Fossil Knowledge, on the other hand, has only been accumulating for a few millennia. The overwhelming majority of words ever printed on dead trees were printed in the past century.

Digitizing this fossil knowledge — that is, making it machine-readable — was the first step in the AI revolution. The next step was transforming human action so that we spend more of our time creating already-machine-readable text. Like I’m doing right now: pouring my brain directly into this and all future machine. I’m communicating with my readers, hopefully making them smarter — but this organic communication of intelligence now produces just as much inorganic silicon knowledge.

At the same time, poor humans have been enlisted by rich humans to explicitly transfer their knowledge to the machine, without even the pretense of communication. The necessity of these legions of humans — clickworkers, ghostworkers, whatever you want to call them — for the refinement of contemporary “AI” systems is well-documented. But it bears repeating.

The phrase “machine learning” should help us remember that the job of more and more people is “machine teaching.” And just like for human learning, we need to pay the machine teachers better.

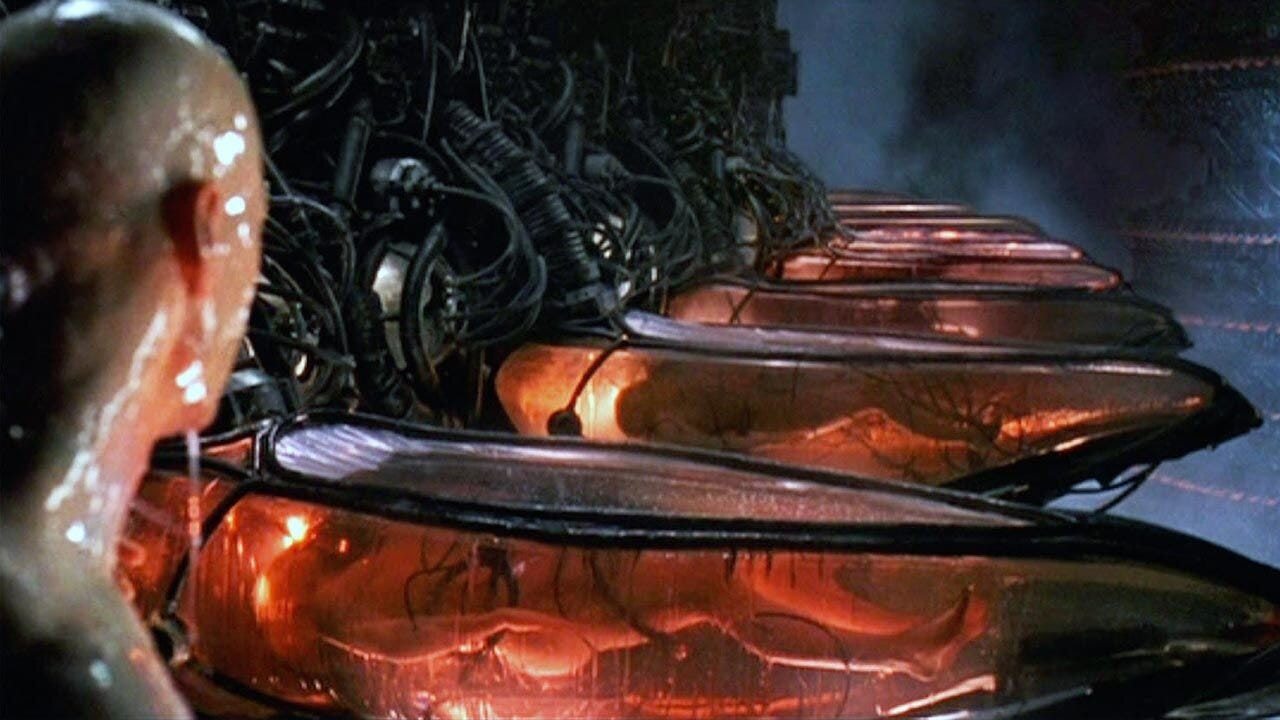

But we’re headed in the other direction. Machines harvesting “human intelligence” to power themselves in a changing world. Indulge me — but TikTok is The Matrix.

I watched The Matrix approximately 100 times when I was a teenage. And the funniest line, to me, was always Morpheus explaining why the machines bothered with The Matrix at all:

Combined with a form of fusion, the machines have found all the energy they would ever need.

Thermodynamically, this is stupid. The machines probably should’ve spent more time perfecting that fusion thing and dumped all the human D-cells down the drain.

But this is because The Matrix is a metaphor. The film is famously based on Baudrillard’s media theory, which posits that our immersive media environment transforms reality into a virtual reality. But you can’t make a blockbuster that’s overly faithful to French postmodern philosophy.2

In order for us Matrix-dwellers to make sense of The Matrix, The Matrix has to involve individualized human conflict and development, a love story, kung fu. And, of course, gun. Lots of gun. To make the machine antagonists’ goals legible, they have to be translated into something we understand: power, in the form of energy.

(It’s possible that some element of my interpretation is contradicted by a film that is not The Matrix (1999). I do not care about this, please do not mention these films.)

But energy is a metaphor. The reason the machines need those humans around is for training data.

So instead of paying machine teachers, the “apparatus” of social media is designed to condition us to teach the machines for free. The gyration of the whirlpool of digital content induces us to both create and label machine-readable knowledge. Someone posts a TikTok, everyone else provides feedback in the form of views, likes, comments. The producers, as I argued Tuesday, are literally addicted to posting. And the consumers get cheap entertainment for free. This is actually The Matrix.

Three arguments why this might make us want to ban TikTok. I don’t agree with all of these, at least not to the same degree, but politics makes strange blogfellows:

TikTok is the same as other social media platforms in this respect. We need to ban or at least heavily tax any platform which is harvesting this “behavioral surplus” (per Zuboff’s Surveillance Capitalism) in order to re-invest it in their models.

TikTok (or TikTok-ism, short-form videos recommended primarily by algorithm) is even better at this than any other platform, and is thus an unacceptable intensification. We should decide on an acceptable limit of how much free machine teaching people can do without explicitly opting into it.

AI is the new technology of war. Behavioral data is the new oil. TikTok is a Chinese company; we are training their war machines. Meanwhile, China bans our social media platforms, bans its citizens from training our war machines. They’re drinking our milkshake. They’re drinking it up.

Check back in tomorrow for the exciting conclusion of Ban TikTok Week!

In terms of immediate particulate production.

Brief aside: in undergrad, when I was first exposed to postmodern theory, I couldn't make heads or tails of it. I concluded that it was best categorized as poetry, another kind of textual communication that doesn't make sense to me. This (mistaken) belief was reinforced by the fact that the main text I was consulting was Baudrillard’s Cool Memories II — which is, literally, poetry.