SIGMA Moves

During the pandemic, I was seduced by a charming British management consultant. A debonair James Bond-type who went from driving a Rolls Royce around his countryside estate to orchestrating the Chilean economic experiment under Allende to teaching Brian Eno about the principles of complex systems in a stone cottage in Wales. Stafford Beer lived a remarkable life,

What the abandonment of the pinnacle of capitalist achievement for the most realistic effort to build cybernetic socialism does to a mfer.

The recent 50th anniversary of the 1973 Coup in Chile has sparked a resurgence of interest in Beer, who is most famous for running Project Cybersyn and thus reforming Chile’s economy under Allende. There has been growing interest in cybernetic socialism over the past decade, starting with Eden Medina’s history Cybernetic Revolutionaries, Evgeny Morozov’s article on Cybersyn in the New Yorker, and a chapter on the enterprise in Leigh Phillips’ and Michal Rozworski’s book The People's Republic of Walmart. Theory streetwear brand Boot Boyz Biz even put out a Cybersyn throw rug.

Just this month, Morozov released an extensive and entertaining retrospective of the entire period in the form of a nine-episode podcast. Although I enjoyed the whole thing, I found the narrative account of Beer’s response to the coup and the general distrust of Allende in the UK most illuminating.

Like many of the postwar behavioral scientists, World War II was a major shock to Beer’s understanding of the tradeoffs between efficiency and command, the last society-wide example of alternative models of organization before the establishment of the American-led capitalism that has dominated during all of our lifetimes. The capacity of this style of systems analysis to enhance organizational capacity might well extend beyond the military sphere.

After the war, Beer became one of the leading practitioners of operations research (something you can specialize in business school today) and worked to optimize the operations of factories and larger corporate organizations. He saw huge success working with United Steel in the 1950s before leaving to found a consulting company—amusingly—called SIGMA.

Much of his management research published in the 1960s and 1970s, including his monumental The Brain of the Firm, has been influential in the theory of management. In Morozov’s telling, Beer’s decision to take time away from this successful career is puzzling; the Stafford Beer of The Santiago Boys is motivated to come to Chile by a combination of professional curiosity at being given the reins of an entire country to test out his theories and some vague lefty sympathies developed as a result of his time stationed in the British Raj. This is narratively convenient, but my read of Beer’s project is significantly more radical—and the result all the more tragic.

Although I’ve been a fan for a few years now, I only just got around to Beer’s 1975 book Platform for Change. This is one of the strangest and most gut-wrenching books I’ve ever encountered.

As someone who reads and writes for a living, in the hope that these actions will change the world for the better, I occasionally experience an odd emotion when I read something that’s decades old that condenses some thought I’ve been grasping towards. Part of this emotion is simple scientific envy, that someone beat me to it; part of it is pride, of wanting to share the idea with my peers and enjoy some reflection of its glory. Beneath these feelings, though, is despair – despair that someone else, someone more famous and smarter and older than me already wrote this idea down and yet it didn’t matter.

Stafford Beer’s writing, career trajectory and just overall weltanschauung had this effect on me. The man:

Was born into aristocratic British society and thus had establishment connections and legitimacy.

Correctly diagnosed a variety of fundamental incompatibilities between our inherited institutions, the contemporary scale of our societies and rapid change in communication technology.

Developed an impressive reputation, giving over 500 invited lectures and frequent media appearances, as well as a flourishing and remunerative career as a business consultant.

Cashed out this reputation and connections in a series of increasingly transgressive attacks on what he saw as a complacent and unscientific establishment. (His inaugural address, upon being elected president of the Operational Research Society, is particularly spicy.)

Actually had the chance to implement his radical ideas at the level of a medium-sized country, and demonstrate at least preliminary evidence for their effectiveness.

The vibe of the back flap of Platform for Change:

I am fed up with hiding myself, an actual human being, behind the conventional anonymity of scholarly authorship

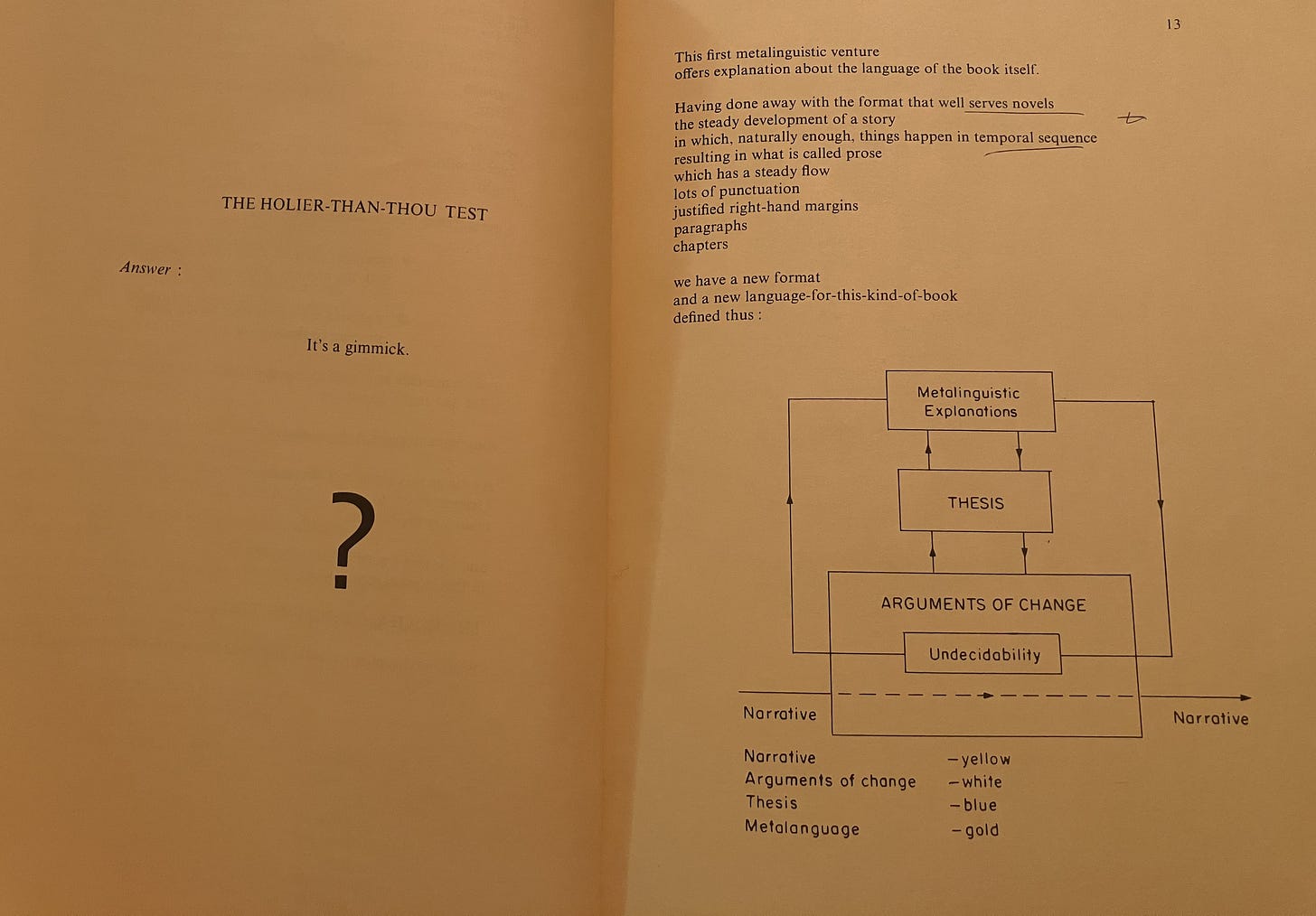

Platform for Change is the culmination of Beer’s project, a manifesto over which he insisted on having total creative control. It’s a testament to both the spirit of the 1970s and the popularity of his previous books that he managed to get a 500-page tome published, let alone one with four different colored pages.

The gold pages, like these, are written in the metalanguage. This is necessary because of the technical inability of our existing concepts, language and medium of communication to make the critique that he needs to make, to propose the solutions that actually address the problem.

I recognize this impulse in myself and in my generation of online-first intellectual activists. Once you start thinking hard and pushing up against the limits of the tools you have been given to think with, it becomes clear that you need to fashion some new tools. This, of course, is a blog about meta-science, where I have frequently argued that the media technologies of linear natural language text and in-line citation are incompatible with a subject as fast-moving as social media.

Beer correctly argues that the format which serves novels (which unfold in temporal sequence) is incompatible with explanations that involve dynamic feedback. He knows that writing a weird book with lots of baroque systems diagrams and color-coded pages will alienate a huge portion of his audience, but he does it anyway, because he thinks it’s necessary to make the point he wants to make. It’s an incredibly long and detailed book, and technically impossible to summarize with normal language, but I found it extremely impressive and compelling.

And yet he failed. Platform for Change was a commercial disaster (obviously), and his serious scholarly output fell off sharply. He was only in his late 40s, potentially at the peak of his career; he could easily have coasted into a career as either a senior management consultant making millions or a contrarian public intellectual.

But the experience seemed to break him; the willfulness that had been necessary to go against the grain won out against the negative feedback he was getting from his increasingly outré efforts. Morozov captures the bathos of Beer’s stubborn insistence on living in that stone cabin in Wales, without running water or a telephone, cut off from the world.

There is a deep, cybernetic irony in this story. Beer’s entire approach to “viable systems” is that they need to adapt to shocks without becoming in some way denatured. A common problem is overcorrection: consider the way that the US responded to 9/11, the permanent expansion of the security state.

Beer’s problem seems to have been the opposite: undercorrection. Once he had settled on the belief system articulated in Platform for Change, there was no shaking it—his refusal to compromise led him down the path from mainstream management consultant to renegade intellectual activist, all the way down to lonely poet-mystic drinking himself to death in the Welsh countryside.

I’ve written about Beer’s concrete proposals for cybernetic government before, and I expand on them below. But the main point of this post is to reflect on the intersection between meta-scientific reform, the history of thought and the sociology of intellectual work inside and outside the academy. Beer’s experience is extremely relevant for anyone trying to change the relationship between academia, science, technology and society, as a guide to both understand the past and orient oneself for the future.

It happens that the Center for Information Technology and Policy, where I’m visiting at Princeton this year, shares a building with the Department of Operations Research and Financial Engineering (ORFE). I was excited to learn this – a chance to walk downstairs and talk to someone about Operations Research, this strange postwar discipline which seems to have absorbed the cybernetic impulse that had flourished across the social sciences and hidden it away in business schools?

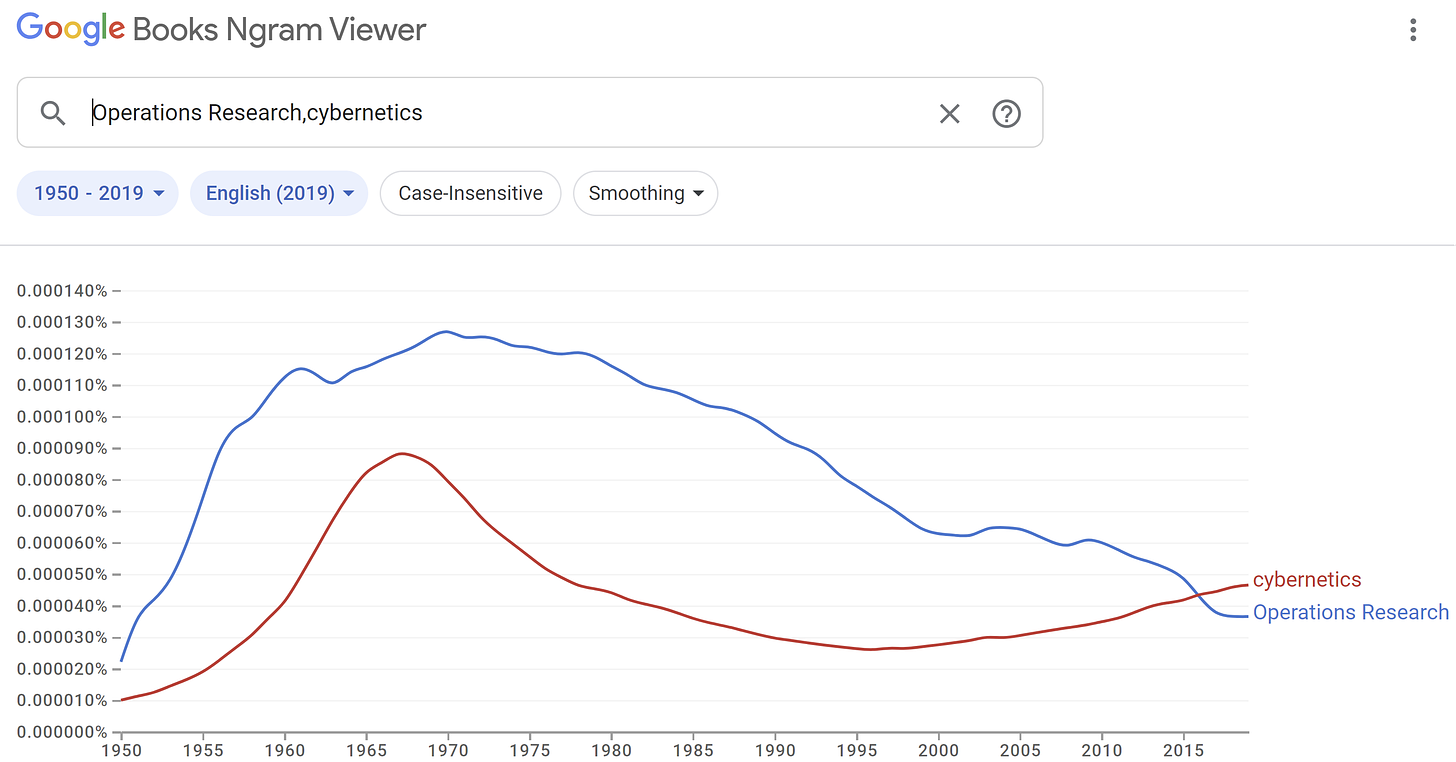

But one of the grad students told me that actually the name is somewhat anachronistic—no one really does Operations Research anymore, it’s all just financial engineering aka math and stats. Indeed, it looks as though 1970, the year Stafford Beer was elected president of the Operational Research Society in the UK, was the peak of the intellectual movement.

Cybernetics, at least, is making a bit a comeback.

Can you recognize an Angel?

Designing Freedom, Beer’s 1974 book, is far more accessible than Platform for Change, and indeed should be required reading for students of economics, political science and the history of science. The book outlines the way that we can (and must) use new information technology to *design* freedom. Beer conceives of a networked economy and cultural sphere that enhances human capacities without warping human desires.

Beer thus follows the humanist tradition established by Norbert Wiener, the grandfather of cybernetics. Weiner immediately understood the implications of his development; in Cybernetics, he describes his attempts to explain what was coming to the heads of the country’s largest labor unions. They didn’t understand or attempt to use cybernetic principles to enhance the effectiveness of their organizations.

Weiner’s second book is called The Human Use of Human Beings, an even broader attempt at outlining a society built on cybernetic principles: the most effective society, he argued, would be able to make full use of each human’s capacities rather than forcing the overwhelming majority of humans to contribute only tightly controlled and alienated labor.

Designing Freedom continues along these lines, a crucial intervention in the tired 20th century debate between government control and “liberty.” Beer talks about a Liberty Machine that is used to create liberty. That is, we should understand that our society is “not an entity characterized by more or less constraint, but a dynamic viable system that has liberty as its output.”

This fatalism is understandable. Capitalism and technology have produced a globe with eight billion humans and no way to slow down. It can feel like there is zero margin for experimentation, that any move away from the present course could spell disaster.

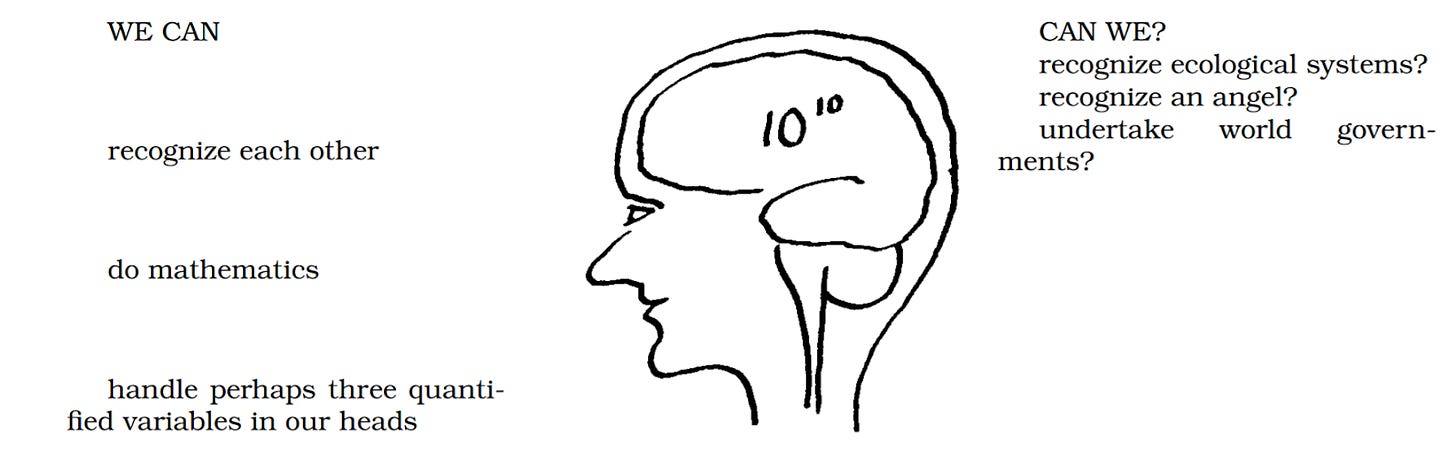

If we want to both radically restructure society and avoid billions of deaths, we have to center concerns about scale. The definition of “Big Data” is often given as “more data than you can fit in your machine's active memory,” but Beer has another threshold in mind, one not ameliorated by Moore’s Law: the human brain.

“Recognize ecological systems” and “Undertake world government” strike me as more immediately relevant, but Beer’s transcendent weirdness peeks through with the phrase “recognize an angel.” Threading the humanist needle requires recognizing that our capacities as humans are indeed unique among beings and yet woefully inadequate for the tasks we ask of individual humans.

But the individual human brain remains a crucial bottleneck for the flow of information. Given certain biological constraints, it is impossible to centralize all of society’s necessary information storage and processing within the brain of a single individual. This problem can be addressed by groups and technology, but this is usually done in wasteful or destructive fashion.

Strict bureaucratic control can enhance the scale at which organizations can act—at the cost of the speed of the reaction or the scope of the action space. Complete decentralization limits the capacity of the organization to pursue strategic objectives, generally collapsing into autarky and self-interest. Designing freedom, in Beer’s view, means designing institutions that allow humans to use their full capacities as humans to regulate society, collectively and at scale.

There is a branch of the anti-tech left that rejects this conception of control-as-regulation, in the naive view that these forces can be contained. (Indeed, both Wiener and Beer were criticized along these lines by the still-Sovietpilled left during their lifetimes.) This view descends from the ironic tendency of some anti-Anglo-imperialists to view the United States government as the only agent of consequence, with a cabal of capitalists directing its violent energies. Morozov’s podcast falls into this trap; while the significant efforts by the CIA he describes did in fact happen, the first episode whips back and forth between the leftist revolutionaries “realizing” that the CIA would “never” allow Allende to win election fairly to Allende winning election fairly.

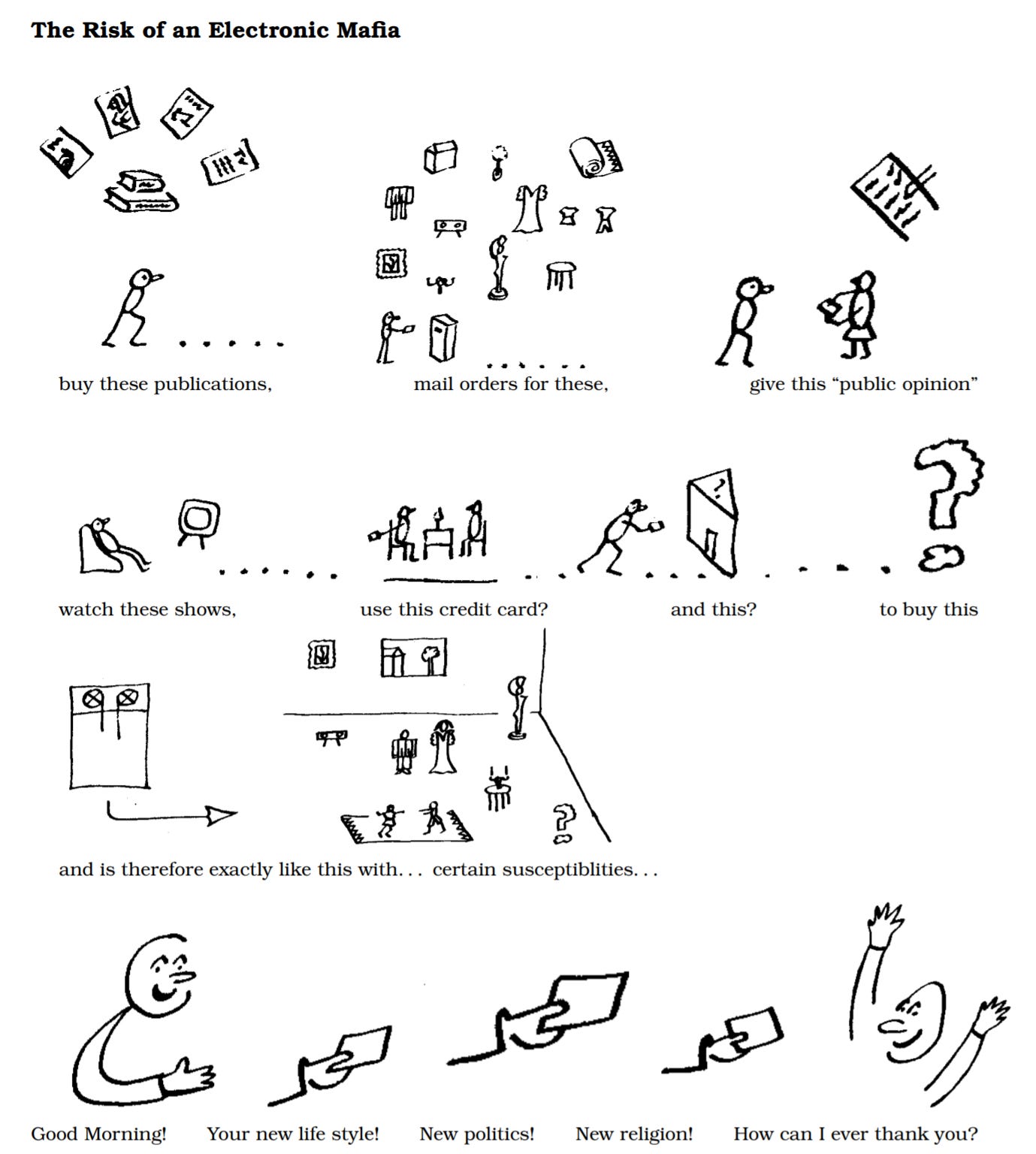

Beer correctly diagnoses this impulse, one that I detest. It is moral narcissism for intellectuals to exhaust their human capital endowments debating about how they can minimize their own sins while the forces of technocapital grow stronger by the day. Beer’s now-quaint description of the threats we face illustrate just how badly we have been losing over the past fifty years—the “Electric Mafia” he fears is easily recognizable in the control technologies of algorithmic feeds and product recommendations

“What is to be done with cybernetics, the science of effective organization? Should we all stand by complaining, and wait for someone malevolent to take it over and enslave us? An electronic mafia lurks around that corner.”

“We allow publishers to file away electronically masses of information about ourselves—who we are, what are our interests—and to tie that in with mail order schemes, credit systems, and advertising campaigns that line us all up like a row of ducks to be picked off in the interests of conspicuous consumption.”

In the absence of an intentional, humanity-enhancing system of electronic communication technology, powerful entities both governmental and corporate will use those technologies to erode our humanity and thus deprive us of liberty without ever resorting to the “man with a gun” who is the primary avatar of unfreedom among people who fear centralized state power.

This is the same kind of insight that I described as “the cybernetic event horizon” in Flusser’s work, and in the same spirit that Deleuze discusses “control” and Foucault “governmentality” (though Beer and Flusser both got there before these canonized wordcels).

Today, it is clear that fears of an “electric mafia” were if anything understated. Effects which are commonly attributed solely to the internet and social media have in fact been developing for decades. But modern communication technology obviously accelerates the trend.

Mark Zuckerberg didn’t wake up one day and decide to cause teenage girls to have panic attacks about not getting enough Likes on their Instagram posts; he and the other electric dons designed and piloted these systems whose output was human anxiety rather than human freedom.

AND DON'T TELL ANYONE ELSE UNLESS I SAY SO

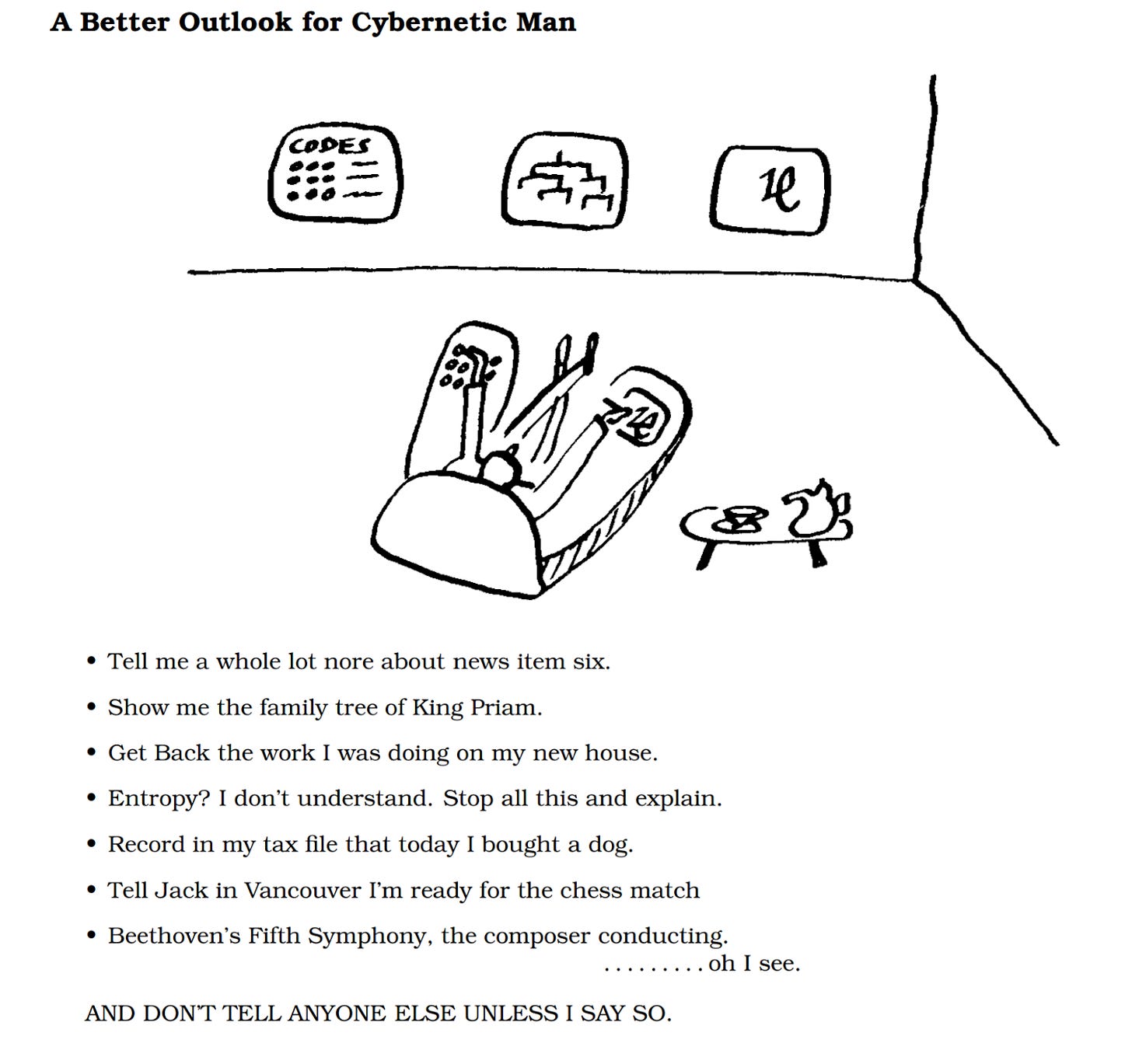

Beer’s vision for how communication technology could be used to enhance human freedom doesn’t look all that different from how we interact with computers and smart devices today. The design of the user interface, replete with armchair and cigar, is perhaps a bit whimsical compared our usual set-up, but the ability to look up information, do a deeper dive on news items, play music and play long-distance chess are all things we can do today.

The one exception is the ease with which this setup integrates information into the user’s tax file. One of Beer’s crucial insights is that increasing the total number of channels of communication only tends to produce confusion and give private actors more leverage. Personal income taxes are an old form of communication between citizens and the state, and they are today such a source of annoyance because they haven’t been overhauled to fit within the rest of the societal apparatus for collecting and transmitting information. Concerns about privacy are misplaced; at present, the only entities who are cross-walking all of the information about individual people are corporate data brokers and the big companies that pay them; doing all of the relevant data collection and synthesis up front would both empower government action and undercut the corporations’ advantage.

But the bigger difference between Beer’s dream and the status quo is the phrase “AND DON’T TELL ANYONE ELSE UNLESS I SAY SO.” This isn’t specifically a privacy concern; he’s also opposing the collection of anonymized aggregate data. The crucial mechanism, what would allow the creation of tools which empower humans to act without warping our desires and indeed our natures, is to cut this channel of feedback from the individual back into the apparatus.

My normative commitment is to human freedom, human agency. The more of ourselves exist in the apparatus, the more agency we offload to it. The radical rejection of technology is simply not an option on a planet of 8 billion. Individual efforts to avoid using modern communication technology are quixotic and ultimately self-destructive, as Stafford Beer’s descent into pastoral mysticism illustrates. The best path I see requires something like his approach to effective communication and governance, to think of engineering a society which produces human freedom while ensuring homeostatic stability.

Operations Research is still a thing, but financial engineering pays better. I think an engineering school concentration in operations research is a wonderful thing. I would take an undergrad engineer in OR over any "data scientist" any day of the week. I will not need to explain what linear algebra is to an OR engineer. I will not need to explain to him/her that there are multiple probability distributions and one cannot simply assume that it is normal because you have a lot of data, and especially not if your variable is discrete (not making this up).

I am not aware of your deliciously-named subject, but he sounds cool enough. I will say that if language limits you, study up on philosophic logic. It is like computer programming, but useless. Ultimately, it is difficult to explain difficult ideas. Unfortunately, clear writing is not all that valued these days. If you work hard, you will get better at it, but the morons will still assume you are using chatGPT because they are incapable of writing and thinking quickly. I am convinced that most of us were surprised by chatGPT's widespread use because we have no need for it, while those struggle with reading and writing are not exactly advertising their crutch.

Similarly, you will hear that financial engineering is "all they do" at Princeton, but if you go to the other 99.99% of universities where Investment Banks and hedge funds will NEVER recruit, and it is all about OR. Ever warehouse, factory and call center uses the principals of operations research. Outside of the wealthy caverns in Manhattan and Chicago, no one else in the US uses financial engineering. I am the odd case in that I graduated from Cornell and worked in finance, but drugs and a prison term after a fight left me in a new place, where I found myself working in a mattress factory. Oddly, I enjoyed it and found myself running the place a few months later (the plant, not the firm). I regret leaving. I work in a government gig that I love now. but I miss modeling games. It is cool to get paid to model out shipping and receiving, then production, then financial stuff. It is a like a game one is getting paid to play. If I had any sense I never would have left my first job out of college, but not all of us are as sophisticated as Stafford Beer. Thanks for the story. I enjoyed it.

You might look at https://web.archive.org/web/20080314192927/http://www.vanillabeer.org/staffordbeer.htm

vanillabeer.org seems to be the site for his daughter, who's documented on Wikipedia as an artist. The original link no longer exists.