You open the app and immediately the algorithm shows you what you want.

All the drivers in the world—and the algorithm someone finds the one who will get you where you want to go, as cheaply as possible!

Uber makes it harder to sustain the myth of “the algorithm.” As I wrote in Mother Jones last month, there are three inputs to the quality of a recommendation algorithm. We tend to focus on consumer data and machine learning expertise, but the third is usually the most important: the size/quality of the “content library” from which recommendations are drawn.

This is easy to think about when it comes to Uber’s “recommendation algorithm.” Geolocation has become mundane; we can at least imagine the process involved in matching drivers and riders, even if we don’t know the technical details.

The Uber recommendation algorithm works better when there are more Uber drivers, near you and willing to accept the lowest wage possible.

Improvements to the Uber recommendation algorithm therefore require interactions with systems external to the app itself: lobbying governments, dealing with lawsuits from disabled riders, breaking drivers’ unions, and even pushing for the development of cars without human drivers.

Despite all the technical flash and “new media” sheen, the same is true for TikTok.

Programming note: It’s Ban TikTok Week here at NMS! In a experimental departure, I’ll post one short article a day. For background, see my talk “The United States Should Ban TikTok” presented at the Notre Dame Keough School of Global Affairs in November 2022.

The economists tell us that the producers of both short car rides and short-form video are “rational actors”—they derive more utility from posting/driving than from whatever else they might be doing, so what’s the problem? Both parties benefit or else the transaction wouldn’t take place.

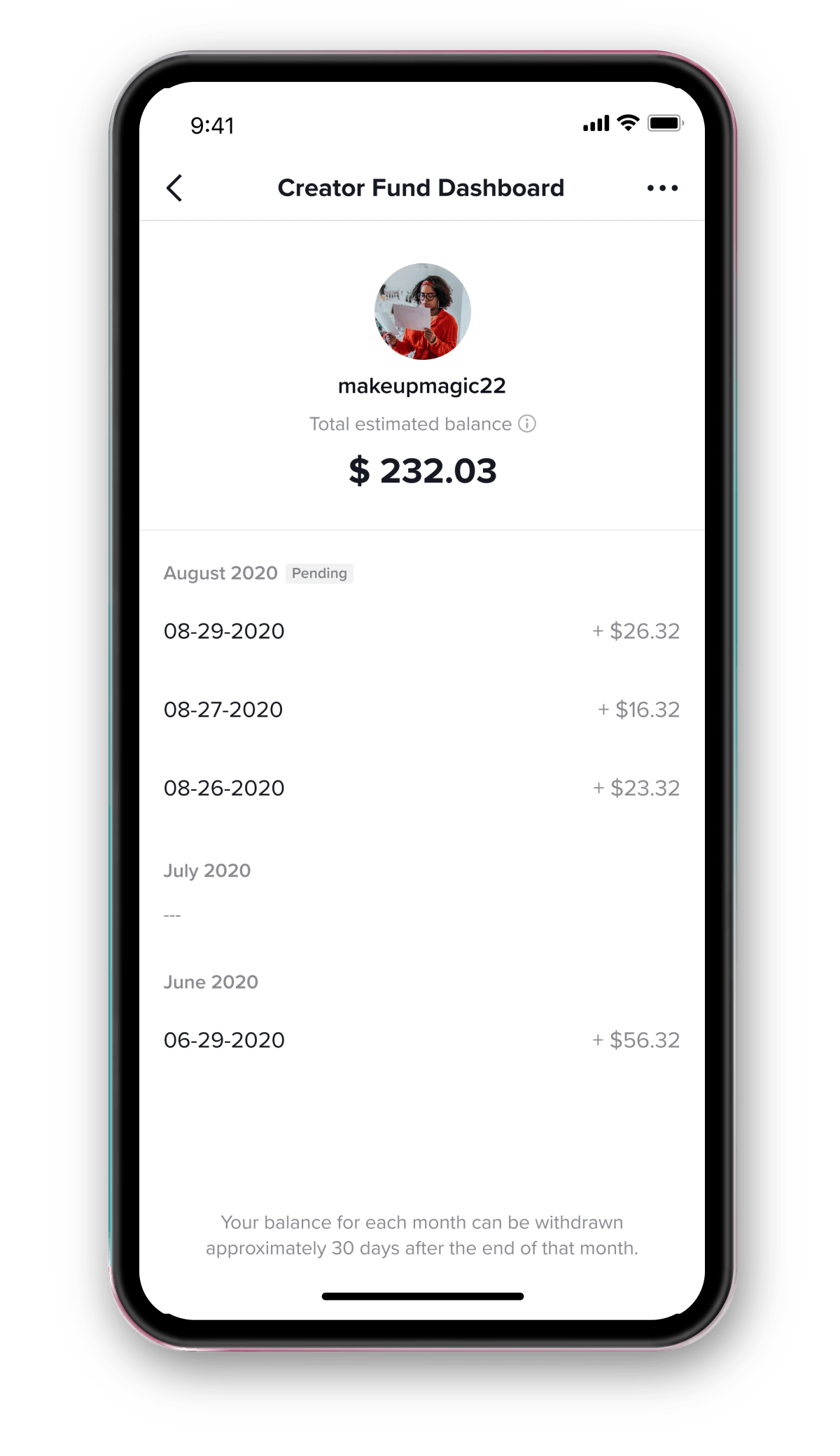

The problem is that the profit margin of these 100-billion-dollar companies depends on running a two-sided market in which they allocate all of the benefits from this transaction to the consumers, leaving the producers with as little surplus as possible, just at the margin between quitting and continuing to work.

In our award-winning paper “Fifteen Seconds of Fame: TikTok and the Supply Side of Social Video,” my co-authors and I demonstrate that TikTok has been remarkably successful in incentivizing the production of short-form video. Compared to YouTube, a dramatically higher percentage of people who leave comments (on political videos, in our case) also produce videos for the app.

This is the basis of the magic of “the algorithm.” TikTok can only show you videos about Capricorn cottagecore carnivores because someone posted videos about Capricorn cottagecore carnivores.

The overall effect of Uber’s algorithm maximizing consumer welfare (at the expense of producer welfare) is up for debate; obviously everyone likes cheap cab rides, but there’s also something to be said for stable, comfortable employment as a bulwark against populism or even more radical politics. Citizens don’t cease to be voters when they clock in.

The situation for TikTok is different because media is not a “normal good” like cereal or cab rides—it is an “information good,” with very different properties. Most salient are evaluation (you can only check whether a TikTok is any good by consuming it — and they’re all unique) and non-rivalrous consumption (unlike a given bowl of cereal, my watching a given TikTok doesn’t mean that you can’t also watch that TikTok).

The above is true of all social media, not just TikTok. But the platform is unique in transcending the social network in favor of the recommendation algorithm. More than 2/3 of time on the app is spent on the algorithmically-generated For You Page. This makes TikTok different from YouTube, Instagram (pre-2021) and Twitter (pre-X).

The latter are truly social networks; the follower/following action is central to how information circulates. This made it possible for creators to accumulate network capital. If your account has a million followers, there’s a certain amount of exposure guaranteed for your posts. From the perspective of creators as economic actors, this ensured a degree of stability and security.

The centrality of algorithmic recommendation removes that stability. Much of the magic of “the algorithm” is the ability to force every creator to compete with every other creator, regardless of the number of followers they’ve accumulated. The “reserve army of the unverified” summoned up by the algorithm enforces precaritazation among all of the posters—just like Uber’s algorithm represents a precaritization of drivers vizaviz the previous taxi system, in which scarcity and safety was enforced by regulation.

Again, in the Uber case, the clearly benefits from lower costs. But for an “information good” like a social media post, the social welfare implications are far less clear. Certainly, many observers seem to think that our information environment is less healthy than it was in the previous, more restricted and regulated media regime.

But there’s another key way in which “the algorithm” is different on TikTok. Uber drivers don’t get addicted to driving in the way that TikTok creators become addicted to posting.

Addiction, in the economic framework, can be thought of as a persistent cognitive bias. Gamblers at a casino are obviously not maximizing their expected returns; they’d end up with more money just sitting on the couch.

The logic of variable rewards is essential to cultivating this bias in gambling addicts. The possibility of hitting it big on the next spin makes it extremely difficult to stick to rational utility maximization; this is literally the mechanism that drives BF Skinner’s operant conditioning. Natasha Dow Schüll’s classic book Addiction by Design explains how the designers of gambling machines take this logic into account to get people hooked on slot machines.

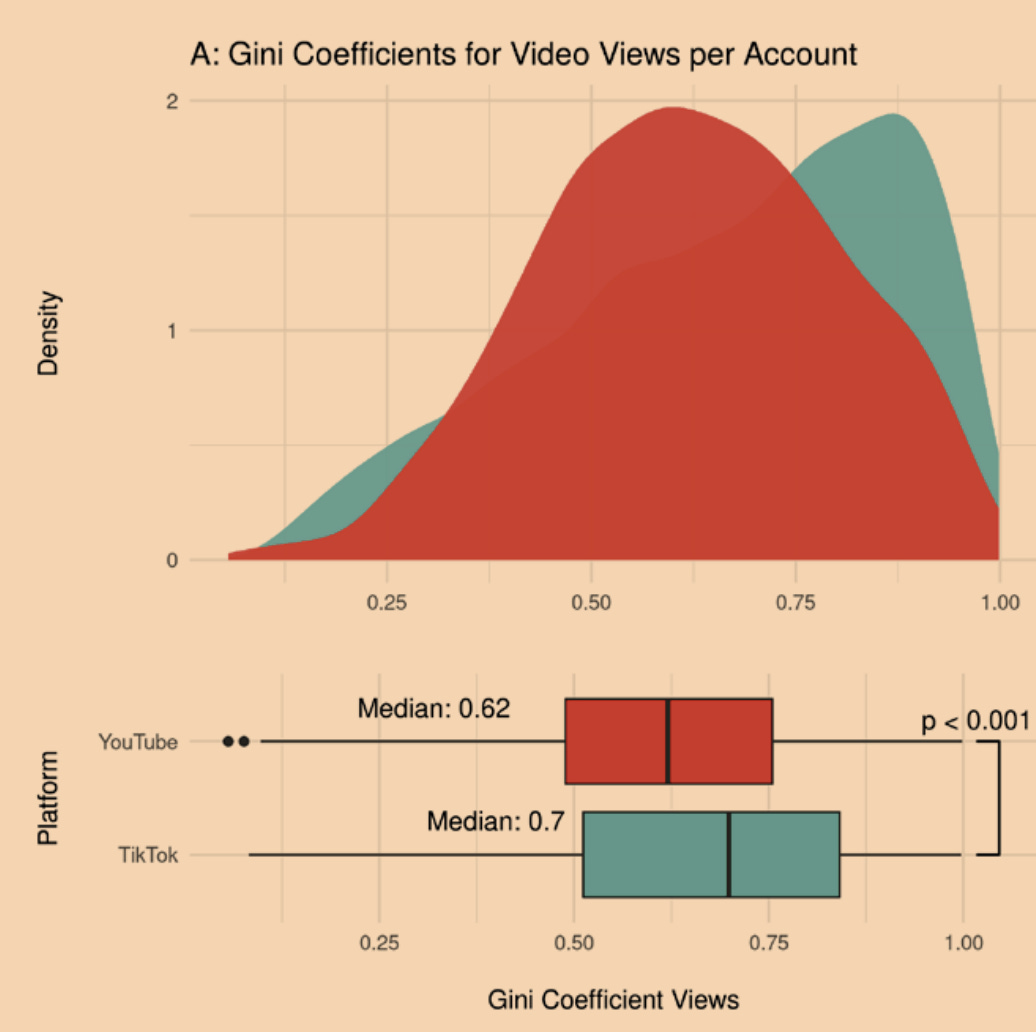

And TikTok’s algorithm works in exactly the same way. In contrast to the social network, in which explicit followers serve as the base audience for each post, TikTok increases the variance in the viewership for any given post — making it much more likely that one will go viral.

To test this, ask a young person if any TikTok post by them or someone they know has gone viral; when I do this to a class of 35 undergrads, usually one or two of them have gone viral themselves. But then ask the same about a post on any other platform. You’ll find that this is much rarer, and that the possibility of going viral is explicitly part of the appeal of TikTok.

Or if you prefer peer-reviewed quantitative analysis, our paper finds significantly higher inequality in the viewership for a given account on TikTok than on YouTube.

So this is the central engine of TikTok, and another way in which “the algorithm” is different here than for Uber: creators are actually posting an irrational amount, investing more time and energy than they rationally should, because they are mistaken about the costs and benefits. Going viral is like the high of winning a big bet, or like the high of getting high: it programs you mostly to want to get high again.

Karthik Srinivasan provides quasi-experimental evidence that this is the case:

“After going viral, producers more than double their rate of content production for a month.”

Many states have a monopoly on gambling — and they still buy ads, in order to make their citizens make a mistake.

That’s terrible — but we shouldn’t replicate it for TikTok, the Uber…but for human communication.

One interesting consequence of the stability loss, that could be cool to measure, is whether "audience capture" happens more on TikTok than on YouTube, i.e., are users swayed by their audience more? Given that they can loose them at any time?

> So this is the central engine of TikTok, and another way in which “the algorithm” is different here than for Uber: creators are actually posting an irrational amount, investing more time and energy than they rationally should, because they are mistaken about the costs and benefits. Going viral is like the high of winning a big bet, or like the high of getting high: it programs you mostly to want to get high again.

And you have made the mistake in believing your cultural training that the sensation that you can read the minds of other humans is genuine.

Ironically, TikTok happens to have a fair amount of content about these and other bizarre phenomena, unfortunately they do not get onto all people's feeds, and most people likely lack the necessary base education to understand the concepts....but at least these TikTokers are trying!