2024 is here, the year of the election. As the world begins to tune in to the greatest show on X, the question on everyone’s lips is:

Why the hell is everybody so old??

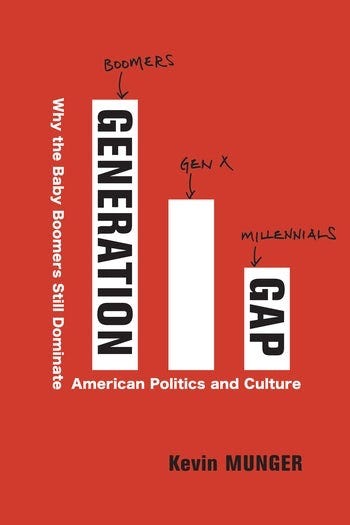

In the summer of 2022, I published a book predicting this:

elite electoral politics will see a clear and extremely high-profile generational turning point in 2024. President Joe Biden begins his term as the oldest President in history; in 2024, he will be eighty-two years old. He at one point indicated that he intends to serve as a “transition” President, and that he might be the first President to decline to seek re-election in decades. If he does run, his advanced age will be a central issue throughout the campaign.

First, the facts: in 2024, either Trump or Biden would be the oldest person to win a presidential election. We have the second-oldest House in history (after 2020-2022), and the oldest Senate. A full 2/3 of the Senate are Baby Boomers!

Not only is the age distribution of US politicians an outlier compared to our past—we also have the oldest politicians of any developed democracy. And not just the politicians, but the voters, too: more Americans will turn 65 years old in 2024 than ever before—and given macro-trends in demography, maybe than ever again.

The approach I take in the book is very different from the rest of my research. In contrast to a tightly-controlled experiment, analyzing phenomena of this scope does not allow for neat causal explanations. The “temporal validity” issues that arise when studying social media are because they change too quickly; here, the problem is more “temporal illegibility,” the inability of our preferred tools to register “causes” that unfold over the course of decades.

Paul Pierson’s excellent book Politics in Time makes this point in excruciating detail. The research methods in vogue in quantitative political science (the ones I tend to use!) are like the vision of the Tyrannosaurus Rex from Jurassic Park: they can only detect movement, at the speeds typical of medium-sized mammals.

A common exercise in research design classes is to discuss the “ideal experiment” to study a given question. If money, power and ethics were no constraint, what experiment would you run? It’s useful, thinking about what it would mean to randomly assign one state to only broadcast Fox News and another state only MSNBC. But the very idea of an experiment breaks down at the scale of generational politics.

It doesn’t even make sense to think about randomizing, say, “generation size” to see how much that causes generational power when a given cohort turns 65. Modifying society at that temporal scale means that there’s nothing left when the experiment is over, no fixed point or control group against which to compare the results.1

The inability to conceive of an ideal experiment suggests that the relevant question is ill-posed. When I talk about “Boomer Ballast,” the outsized power wielded by this generation in the 2010s and 2020s, people sometimes ask: “how much of this is just because there were so many of them born at the same time?”

This question is unanswerable and therefore, in my view, meaningless. Just as the speed of social media makes “ceteris paribus” (all else equal) comparisons impossible, so does the speed of generations vizaviz the temporality of the human life cycle, the age of the country, etc.

And on the “just because” part. I’ve found that this is a common response to the presentation of a descriptive research result: people chalk it up to the first causal mechanism that pops into their head, in a dramatic inversion of the usual skepticism applied to causal claims.

Both this issue and the T.Rex-vision problem are legacies of the misapplication of Hume’s model of causality, itself a more narrow definition than Aristotle’s…but back to Boomer Ballast.

The challenge of differentiating the effects of age, time period, and cohort (the “APC” problem) is a statistical nightmare—especially because the data we have access generally only goes back a few decades. But the premise of the problem is that, yes, all three of age, period and cohort have effects…so by definition, no effect is just because of any one individual cause.

That’s why I don’t really care about resolving the APC problem. My claim is that a confluence of largely unrelated factors will cause generational conflict to become a central cleavage in US politics in the 2020s. This means holding fixed the time Period of analysis and treating Age (there are a lot of old people) and Cohort (those old people are Baby Boomers) as two distinct types of causes of the present generational conflict.

The politics of generations is affected by raw demography, growing longevity, and unequal power accumulation alongside the rapid evolution of communication technology and the development of online communities that enable younger generations to ignore geography and the need to gain knowledge from elders. The two main “causes” are the accumulated power of the Boomer generation and the information technology revolution; the tension between these causes is the main “effect,” generational conflict, played out in the realms of politics and culture.

This conflict has a zero-sum dimension, as younger and older generations jostle over a fixed fiscal budget, with mutually exclusive preferences. Boomers want more money for Medicare and Social Security; Millennials and Gen Z want money for student loan debt forgiveness and climate change amelioration. But in another important sense, the tension between Boomer Ballast and the internet revolution is negative-sum, and potentially even more concerning for the viability of the United States as a system. This insight comes from Karl Deutsch’s classic 1963 book The Nerves of Government, which conceives of government through the analogic lens of a brain—or, updated to today, as a computer.

The book is broadly concerned with communication, the way that information flows from citizens to the government, within the government, and then back to the citizens in a circularly causal feedback loop. In contrast to many of the broad accounts of government—before or since—Deutsch conceives of government as cybernetic, and thus primarily concerned with adapting to a perpetually changing environment. This dynamism produces an unresolvable tension; between the openness to new information required to adapt, on one hand, and the commitment of societal resources required to address present problems:

“In addition to being invented and recognized, new solutions and policies must be acted on, if they are to be effective. Material resources must be committed to them, as well as manpower and attention. All this can be done only to the extent that uncommitted resources are available within the system” (p164).

Applying Deutsch’s framework to the biological realities of the human life cycle, we see that our society has an unusual degree of resources committed. The government cannot change the shape of the demographic pyramid, except decades in advance. Boomer Ballast means that a disproportionate amount of our economic, social and political human capital is invested in an illiquid response to the postwar, 20th century environment. Our demographic structure, compounded by our economic fortunes, granted us an unusually high degree of adaptability. And we flourished.

But the Boom in adaptability led naturally to a bust. In normal circumstances, this would still entail some future cost, as we had fewer untapped resources to devote to new problems. Our society is like a sluggish laptop with too many browser tabs open, too many resources devoted to maintaining things as they are, to be able to do new things quickly.

The advent of the internet compounds the problem of our present over-commitment. It will take decades for the full implications of the internet and related technologies to filter through and fundamentally reshape human society, but Boomer Ballast means that this process is stunted in the contemporary United States.

To deploy new “solutions and policies” suited for the digital age, we will need to move beyond the inherited structures of the 20th century. The biological passing of the Boomer generation is inevitable, but the organizations and structures the Boomers built or reinforced will long outlive them.

Deutsch sees this as an inevitable challenge facing societies that hope to thrive beyond a single human lifespan, and he warns us to “avoid the idolization of ephemeral institutions”—or, in DJ Khalid’s terms, The First Amendment is Suffering From Success. We must be willing to acknowledge that institutions designed for past times and past generations cannot possibly take advantage of contemporary technology and the human social structures it makes possible.

And we must also ensure that the conditions are right for new generations to build institutions in their place. At the risk of getting too cybernetics-y, a final quote from Deutsch:

The demobilization of fixed subassemblies, pathways or routines may thus itself be creative or pathological. It is creative when it is accompanied by a diffusion of basic resources and, consequently, by an increase in the possible ranges of new connections, new intakes, and new recombinations. In organizations or societies the breaking of the cake of custom is creative if individuals are not merely set free from old restraints but if they are at the same time rendered more capable of communicating and cooperating with the world in which they live. In the absence of these conditions there may be genuine regression (p171).

Genuine regression. Flusser’s fall into unconscious functioning is the result of being surrounded by technical images we cannot understand or control. Deutsch argues that a similar result occurs when individuals who are set free from “the cake of custom” are not simultaneously empowered to communicate and cooperate with the world.

That’s an excellent description of what’s happening today: a fully armed and operational internet/social media/smartphone stack, deployed to the majority of humans in under a decade, is reshaping societies, economies, cultures, families. But because this “freedom” comes without increased capacities, it produces mostly meaninglessness, alienation and vitriol. And Boomer Ballast makes the problem much worse.

Am I able to provide maximally rigorous statistical evidence for the previous paragraph? No, sorry, we live in a fallen world, and the position that we can know nothing unless proven the highest standards of rigor is cheap positivist nihilism. My book triangulates various kinds of evidence towards this central claim, and history (rather than contemporaneous peer reviewers) is the only real judge of the value of my perspective.

And so far, in my humble opinion, so good—2024 will be the year that Boomer Ballast becomes impossible to ignore. The demographic structure of the United States is as much a political institution as are presidential primaries, and it deserves full consideration by political scientists as such.

Much more, dear reader, if you buy my book and subscribe to my blog.

Early-career John Dewey, when confronted with the epistemic challenges to science/democracy posed by Walter Lippmann, considers biting this bullet: he sees the Soviets as having an advantage over democracies because they are actually able to conduct five-year-long experiments. (They weren’t, actually, but Chinese cybernetics comes much closer to fulfilling this vision, of crossing the river by feeling the stones.)

Eventually he realizes that he cares more about democracy as creative freedom than he does about scientific certainty—a decision with which I agree. Of course, contemporary scholars of Dewey are frustrated by the imprecision of his use of terms like “democracy” and “science,” but that’s sort of begging the question.