The 1st Amendment is "Suffering from Success"

and TikTok is incompatible with human dignity

Many political scientists are coming around to the idea that the United States' present dysfunction is insoluble without reforming our electoral institutions.

The general argument is simple. The words that the Founders inscribed were based on the socio-technical context in which they lived. Even if we grant that they were wise when written, the fact that the institutions defined by the Constitution were so well-designed for the tiny, agrarian original thirteen states means that it is necessarily ill-suited for the United States of 2021.

Perhaps the anti-majoritarian, resistant-to-change elements of those institutions are what have allowed them to persist for so long; in any case, the accumulated and accelerating changes to the scale, politics, technology, economy (etc) of the United States combined with our static Constitutions means that things are out of whack.

I am (predictably) most interested in the technological angle. We are familiar with this argument when applied to the Bill of Rights. Sure, the Founders enshrined the “Right to Bear Arms” in the 2nd Amendment, but at the time that meant a muzzle-loading musket that a well-trained militiaman could use to fire one round a minute, not the semi-automatic weapons that needlessly amplify the death counts of America’s mass shootings.

This line of critique also applies to our beloved 1st Amendment.

During the pandemic, I went slightly insane. Thankfully, I managed to sublimate some of my manic energy into the study of midcentury trends in social science and technology. A central premise of this blog (and much of my scholarly research) is that the magnitude of the technological shock of the internet, smartphone and social media is so large that we should abandon most existing premises and theories and just try to figure out what the hell is going on.

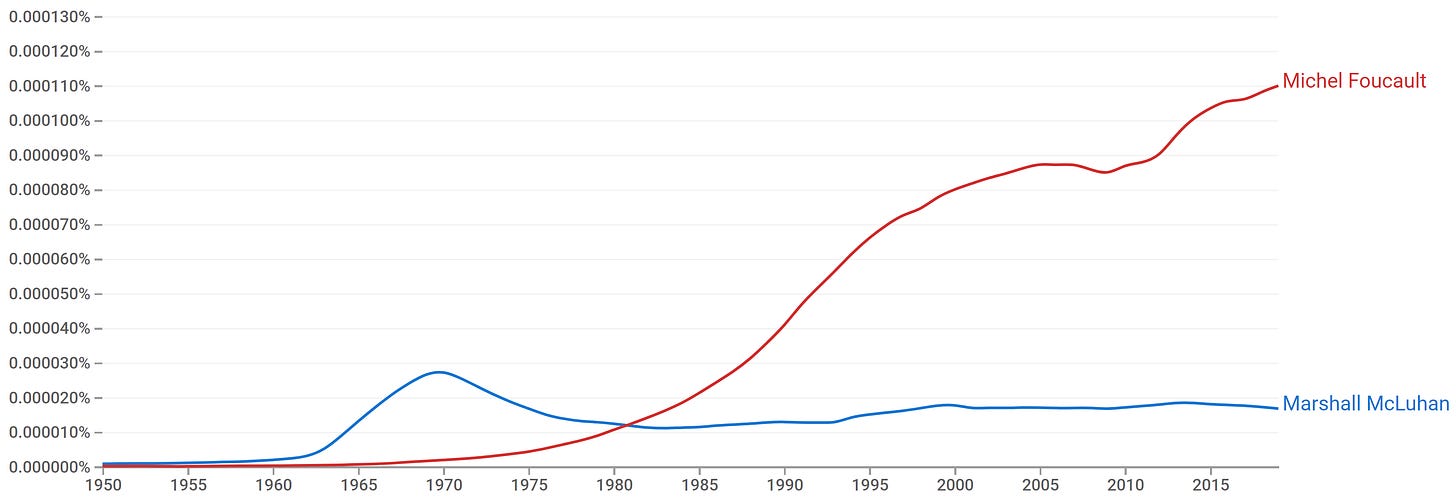

That is: we need more McLuhan.

McLuhan is the arch technological determinist, and his star has faded as that perspective has diminished in stature. The emergence of critical perspectives provided a necessary corrective, but as I have argued before, the pendulum has swung too far: social critique based on ideology and systems of oppression has, ironically, become hegemonic in anglophone intellectual culture.1 In particular, the critique of power is ill-equipped to explain change: why is this happening now, not either earlier or later.

It’s difficult to overstate the nature of McLuhan as a North American intellectual celebrity in the 1960s and 70s. He has a cameo in Annie Hall where the setup of the joke assumes that the audience member will recognize him on sight and that conversations about his ideas are commonplace.

McLuhan’s most famous quip is that “the medium is the message.” A less cryptic gloss of his argument:

The naïve view is that new media technologies add to pre-existing social/economic/political/cultural structures. This is incorrect; new media technologies fundamentally re-arrange those structures.2

And all technology is media technology.

Although this category is almost never used today, McLuhan was interested in the effect of electric media. We talk about digital media, about radio or television. But all of these share the essential quality of instantaneity. Electric media, which allows information to travel arbitrarily quickly, has fundamentally reorganized society’s relationship to time.

It’s about Time

Although the contemporary hysteria about social media makes earlier critiques seem quaint, it is important to remember that midcentury observers were furious about the effect of television. It was too easy to consume, turning people into lazy consumers and eroding our shared commitment to building a vital public life. Robert Putnam’s magnum opus on the decline of American community argues that the effect of television was larger than the effect of the flight to atomized suburban living and the effect of the rising pressure on workers and the two-earner household combined.

Even the Vatican knew something was afoot. Pope Pius XXII wrote, in 1950, that

It is not an exaggeration to say that the future of modern society and the stability of its inner life depend in large part on the maintenance of an equilibrium between the strength of the techniques of communication and the capacity of the individual's own reaction.

Regardless of its effect on the stability of our inner lives, television was a technology that served the interests of the powerful quite well. It kept the masses happy and sedate, allowed elites tight control over the media environment (coinciding with the low point of political polarization this century) and provided unprecedented opportunities for advertising. Social media is keeping up its end of the bargain on the third point at the obvious expense of the second, and today’s masses are anything but happy and sedate.

At this point, the wag will say “bruh this argument is old af, have you even read Plato’s Phaedra? Socrates said that writing sucks because it will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it, because they will not practice their memory.”

Socrates was right! And all of the critics who said that new technologies would change the nature of human beings and our relationship to society were right! Each of them appears in hindsight to be a crank with respect to each new technology; McLuhan’s insight was to provide a unifying framework.

Now, it’s unclear if these changes were good. The normative argument is still very much in play. But McLuhan is saying that these changes are real, so real that it is literally impossible to imagine Socrates’ sensorium, let alone his way of thinking or relationship to society.

Returning to time, McLuhan has a useful normative perspective. In a book review of political scientist Karl Deutsch’s The Nerves of Government (which is shockingly good), he quotes the following passage:

When we defend a man’s dignity, we defend his ability to use his personality; we defend him against an intolerably high speed of learning, an intolerable speed of changing his behavior—intolerable, that is, because incompatible with the continuous functioning of his self-determination, his autonomous learning.

This conception of human dignity rings true, at least within the broad liberal framework that undergirds the post-Enlightenment Western thought. And it suggests an obvious culprit of the nihilistic malaise creeping into the lives of the children of electric media.

McLuhan:

in periods of notable technological change, men lose most of their dignity and autonomy. Electric speed-up of data transmission and retrieval renders the age-old habits and patterns of visually classified knowledge (including our educational, political and commercial establishments) quite hollow and inept…those who struggle to maintain the older patterns of perception and procedure in their lives are automatically deprived of their autonomy and dignity

Young radicals across the political spectrum can see what happened. Right-wing internet teens are obsessed with the idea of a RETVRN to traditional (pre-electric media) culture; left-wing internet teens are obsessed with radical eco-terrorism and the writings of Ted Kaczynski.

Meanwhile, Sad internet teens are developing a “mass sociogenic illness” after spending thousands of hours in isolation watching TikTok, the fastest and most powerful media ever invented.

And popular internet teens work full time in fancy lake houses and shopping malls, bouncing around like marionettes and scheming up “pranks” in the hopes of appeasing the protean whims of a catatonic audience transmitted through an all-knowing and unknowable algorithm.

You know. Standard autonomous, dignified stuff.

We’re Gonna Need New Humans

As I argued in Facebook is Other People, much of the misery of social media is simply because it forces us to accurately observe the misery of those our society has failed.

Social media thus cannot be fixed without fundamentally reorganizing society to account for the reality of the internet. The people in power — Zuckerberg, Biden, Bezos, McConnell, Dimon, Bacow, Sulzberger, Eisner, Murdoch — would really rather pretend that things are fine: a little tweak to the Facebook algorithm, a new branch of the federal bureaucracy, and we’re back to serenity, trusting that the country is in good hands, and especially economic growth.

The first step is to figure out how to actually take care of each other. The next many steps are to re-organize literally everything, a process that will take decades.

A sobering claim, but a comparison to the effects of the printing press is illustrative. Many observers have drawn an analogy to this other revolutionary media technology, sometimes drawing the pat conclusion that the printing press led to the religious wars of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation in Europe and thus that social media will do the same.

The reality is both more complicated and more expansive. The printing press did more than inspire strife by allowing for the proliferation of narratives that competed with the dominance of the Church (although it did do that). 17th century Europe was not the same as 15th century Europe with more books lying around, giving the tiny percentage of the population who was literate a more diverse library.

Instead, the printing press created the conditions for new categories of thought, new moral frameworks, new kinds of government, new institutions, new humans. A person who learns about the world through books is importantly different from a person whose only knowledge of the world comes from interacting with other humans.

Neil Postman—a Communications scholar working in the McLuhanian tradition—presents what I think is the most effective historical analysis of the political effects of the printing press. In some ways, he argues, we got lucky: in the wake of the spread of printing,

something quite unexpected happened; in a word, nothing. From the early seventeenth century, when Western culture undertook to reorganize itself to accommodate the printing press, until the mid-nineteenth century, no significant technologies were introduced that altered the form, volume, or speed of information.

As a consequence, Western culture had more than two hundred years to accustom itself to the new information conditions created by the press. It developed new

institutions, such as the school and representative government. It developed new conceptions of knowledge and intelligence, and a heightened respect for reason and privacy. It developed new forms of economic activity, such as mechanized production and corporate capitalism, and even gave articulate expression to the possibilities of a humane socialism. New forms of public discourse came into being through newspapers, pamphlets, broadsides, and books…

The fading socio-technical stack of the past five hundred years was far from perfect, but it made possible the human flourishing we have seen over the past centuries. If the printing press and the internet are media technologies of the same magnitude of impact, we will need to develop a new socio-technical stack made of cultural technologies that we cannot yet imagine.

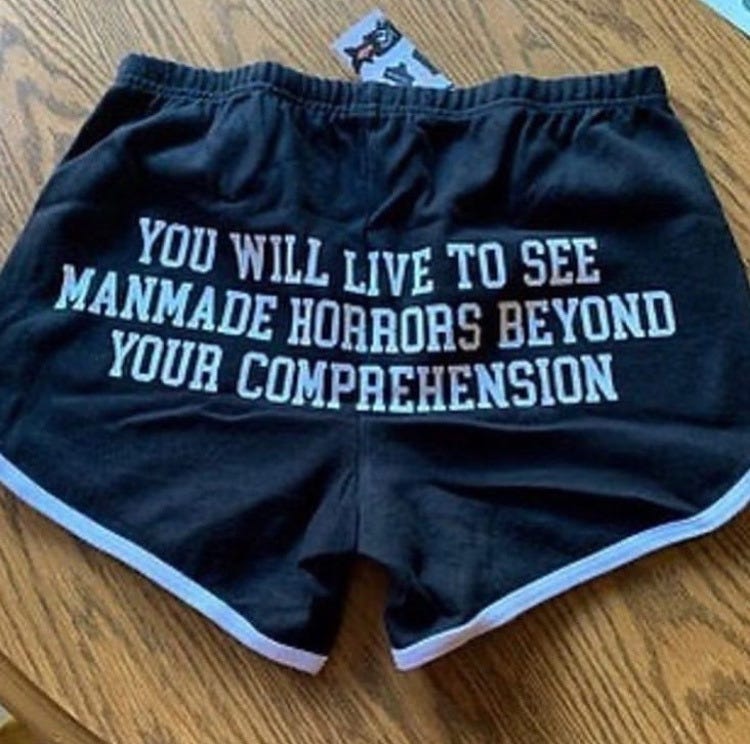

And this assumes technological stability, that human-rate processes will enjoy enough time to adapt. If new media technologies continue to emerge, human dignity and autonomy may not have a chance to operate; we may be perpetually destabilized, buffeted by inhuman processes of information-commodity flow, at the mercy of man-made horrors beyond our comprehension.

Ok Whatever…What About Fake News?

Part of why McLuhanism (now broadly called “media ecology”) fell off is that it neither centers the historical processes currently in vogue in the humanities camp nor produces the specific testable hypotheses that constitute Truth in the eyes of the positivists.

The highest-status positivists tasked with studying emerging media technologies seem to have decided that “Fake News” is important, so perhaps media ecology can explain that phenomenon.

Postman:

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution stands as a monument to the ideological biases of print…

Take a second to think about the literal, originalist interpretation of the last three rights enumerated in that Amendment. The freedom of speech, the freedom of the press, and the freedom to peaceably assemble. Each of these rights is in fact referencing a specific technology of communication, defined either by the constraints of the human body (perhaps enhanced by horse) or the constraints of the printing press as it existed in the 18th century. At the time of the Revolution, there were fewer than fifty newspapers “each producing a four-page issue every week.”

Paul Revere is a media technology!

There are literal mountains of case law and legal opinions about the First Amendment; if that’s what you want, you should be reading a law blog. I am less interested in legal doctrine than in understanding the technological shocks that have destabilized the relationships in our socio-technical stack, in the hopes of discerning the social re-organizations and legal reforms that will allow us to adapt to these new technologies.

Postman usefully defines the stakes beyond the technological; the naïve response to the above critique might be “let’s restrict the number of presses [websites/platforms] and the rate at which they can produce issues [posts].” Pandora is out of the box. Looking to the past, we see the fundamental values enshrined in a socio-technical context defined by

the literate, reasoning mind as fostered by the print revolution: a belief in privacy, individuality, intellectual freedom, open criticism, and community action.

Again, the scope of the political reorganization occasioned by the print revolution is difficult to overstate. The pre-print world simply had different humans and human societies—and the architects of the American Experiment designed institutions to fit those humans.

Those institutions

presume and insist on a public that not only has access to information but has control over it, a people who know how to use information in their own interests…that when information is made available to citizens they are capable of managing it. This is not to say that the Founding Fathers believed information could not be false, misleading, or irrelevant. But they believed that the marketplace of information and ideas was sufficiently ordered so that citizens could make sense of what they read and heard and, through reason, judge its usefulness to their lives.

The problem of Fake News isn’t reducible to The Algorithm or The Russians or The Macedonians (although they’re not helping).

The present informational dysfunction is deep. The components of our interlocking techno-social stack—the education system, the general idea of democracy, the specific institutions of American democracy, science, journalism, capitalism—all rely on the assumption that “when information is made available to citizens they are capable of managing it.”

The internet revolution has rendered this assumption laughable.

We need time, first to adapt our knowledge production system to the new reality and then to use that new system to build out new social norms, politics, economics, culture, morality. The first step is to give more individual humans and small groups time: slack time, to adjust themselves and their relationships to contemporary reality.

In my view, UBI is the simplest and fastest solution; regardless of whether it’s the best solution, simple and fast are relevant criteria. In Bullshit Jobs, David Graeber argued for a UBI on the grounds that it would allow people to quit their terrible, pointless jobs and have a second to breath, to genuinely make choices about their lives. The recent, record employee shortages and the Great Resignation produced at least in part by government spending in response to Covid have generated unprecedented leverage for workers, vindicating Graeber’s view.

Many people were able to do new and interesting things, to develop new ideas and imagine new ways of living. Although these effects were far from evenly distributed, I am genuinely optimistic about the shock to human free time and thus creativity that resulted from this period.

In my opinion, the aspect of the Internet Revolution that we need to get a handle on first is how it has affected our ability to make sense of the world, both in terms of individual perceptions and group decision-making. Our society is an awkward teenager in the middle of a growth spurt: the relationship between our limbs has rapidly changed, and our sensory apparatus doesn’t quite know where everything else yet.

Twitter elevates some aspects of communication and suppresses others; it is not, however, a platform conducive to deliberation. The Founders and other proponents of the Enlightenment believed that beneficent Reason could be relied upon as part of the governing apparatus, and this belief made more sense as part of their socio-technical stack than it does today. Twitter is effective at calling attention and breaking news; we have little evidence to suggest that Twitter is effective at developing solutions to the problems we face.

The number, scope and magnitude of the individual technologies comprising the Internet Revolution is astounding. At present, we have little control over how they are combined and how they fit into our lives. A handful of aggressive corporations have reduced the choice space dramatically, and they have every interest in presenting the current iteration of internet technology as inevitable. We have raced through hundreds of possible technological ecosystems in my lifetime; instead of adapting to each in turn, giving each human and each society the necessary time to re-orient themselves, we are continuously pummeled by innovation, robbing us of dignity and autonomy. Few of the erstwhile centers of power have any idea what to do; the upstart technologists posture as if they do, but epistemically, they must be mistaken.

We could have cheap, durable mobile devices with no functionality other than phone calls, SMS and GPS, for example; most of the important safety gains provided by smartphones with none of the enervating downsides. I would love to learn to live with one of these devices instead of what I have now, to at least have it as an option some days.

The existing social media platforms offer some variety in their emphases and affordances, but they are united in their business model of gathering data and serving ads. There is an unexplored space of possibility if we remove that constraint. I’m a fan of the framing proposed by New Public: we need to create online spaces that are funded in a different fashion, so that people can figure out how to use them. The rise of pseudonymous Discord communities funded through monthly donations provides one example, a combination of modern technology with the playful, uncommodified culture of early web forums.

There is a role for legislation, as well. Some European legislators have made it illegal for large corporations to send emails to employees after work hours. This particular intervention will surely reduce economic productivity and growth; more broadly, government restrictions like this are a blunt instrument that inevitably produce deadweight loss. These are real costs. But given what I see as the stakes, they seem like worthy ones.

All of these are short-term, stopgap solutions to wrest back some human autonomy and dignity. Humans and our societies are the only actors capable of adjusting ourselves to the reality of the technology we have created; but we need time to make that adjustment.

Or perhaps I’m wrong, and America’s trusty public servants have crafted a law that will restore the balance we so badly need without in any way affecting the broader relationship between technology and society. Time will tell.

A key part of this story is the growing divide between the “Two Cultures” in the Western intellectual tradition. Humanities scholars (and scholars in the more qualitative, humanities-inflected part of the social sciences) might justifiably bristle at the idea that their frameworks are dominant. STEM is clearly winning in our society as a whole, and quantitative (“positivist-ish”) social science is where the money and power lies.

That’s all correct — but the depth of the intellectual divide means that the landscape looks very different from each side. It is obvious that we need more critical/humanities perspectives in STEM fields, and many people have made arguments in this direction. My claim is that the converse is also true: we need more STEM perspectives in the critical humanities. The latter argument is rarely made because of the obvious power imbalance across the intellectual divide. But this is central to my project; I’m trying to do the work to meet humanities people where they are, and to demonstrate the value of centering technology.

These interdisciplinary forays always involve stepping on toes — especially, again, given the power imbalance. But I think they are necessary.

The naïve statement of the technological determinist position is that technology is independent of society, that it is the sole cause of history. Existing social structures absolutely affect determine the way that technology is used, and critiques of power are useful in tracing how this plays out. The incentives and decisions of powerful actors—including things like the dominance of the global capitalist system, the legacy of racism in the United States, the moral framework that governs a given culture—are crucial, especially in the short run and especially when the magnitude of the technological shock is small.

But in the long run, when the technological shock is large, societies adapt to the new possibility frontier created by those technologies. The existing power dynamics shift, although almost never entirely. Within a given society, weaker actors try to use new technologies to gain power; established actors initially try to restrict its use to maintain the status quo, and then try to coopt it when that becomes impossible. These dynamics are important, and notice that I invoke the framework of power throughout this essay.

Societies which do not take full advantage of powerful technologies are at serious risk of being dominated by those who do. Agriculture may have been humanity’s original sin, replacing the relatively egalitarian arrangements of the hunter-gatherers with the hierarchy made possible by specialization and accumulation, but there certainly aren’t a lot of hunter-gatherers left.