things will have to change

Social Science in the age of AI

Part of my integration into Italy has been to read classic Italian literature. My favorite so far is Lampedusa’s The Leopard. It’s kind of like the Italian Confederacy of Dunces in that was written by a complete literary outsider and only published posthumously, and that both are detailed depictions of a distinctive Southern culture and of a particular intellectual outsider despairing of cultural decay. Paralleling the respective cultures, the American book is about a deranged autodidact and the Italian book is about a whimsical Sicilian nobleman. Both of them love to eat (hot dogs and maccaroni, respectively).

The Leopard is set during Italian unification (the risorgimento) and broadly depicts the way in which cultural and political changes play out in the more remote regions of the young country. The most appealing character, the protagonist’s nephew Tancredi, is a dashing soldier and womanizer who gets the novel’s most memorable line. As the Sicilians worry about how the new regime will impact their way of life, Tancredi offers a pragmatic approach to the problem:1

If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.

Academia currently faces such a revolutionary threat with AI.

In the nearly five years I’ve been writing this blog, and the ten in which I’ve been studying digital media, I’ve been consistently skeptical of new technology. I’m not a tech booster, but (or because) I lean towards technological determinism: the view that technology is the most important institution, the one which structures downstream political institutions and thus also beliefs, strategies and outcomes. It is incredibly important that we get the technical layer of our institutional stack right; meanwhile, the default political science view treats technology as an institutional add-on, a minor curiousity.

Here I’m explicitly seeking to marshall all my meager epistemic authority and ideological (anti-tech) legitimacy to the following claim:

AI is now too powerful to ignore. Claude Code with Opus 4.5 is indeed a step change in LLM capacity. If the last time you tried an LLM was 2023, or even, like, October 2025, your understanding of the situation is seriously out of date. If we want human expertise to remain valued and valuable, academic institutions are going to have to change.

It wasn’t obvious that this was going to be the case; I wish that this wasn’t the case. Or at least that first sentence — I’ve been loudly criticizing our institutional setup ever since I got my PhD. There’s an irony that the most intense critics of a system eventually come to appreciate the central value of those systems.

I don’t want academia to be destroyed, but the status quo is simply no longer possible. Our institutions were built around the technology of the printed word; we have accomodated the internet, if not fully embraced it, but AI represents a new level of existential threat. What are some diagnostics?

I have a concrete prediction: this is the year in which we see quantitative evidence of AI’s impact in the production of research. This means at least a 50% increase above a linear extrapolation in the number of papers submitted to journals and grants submitted to funders.2 These systems are already under serious strain.

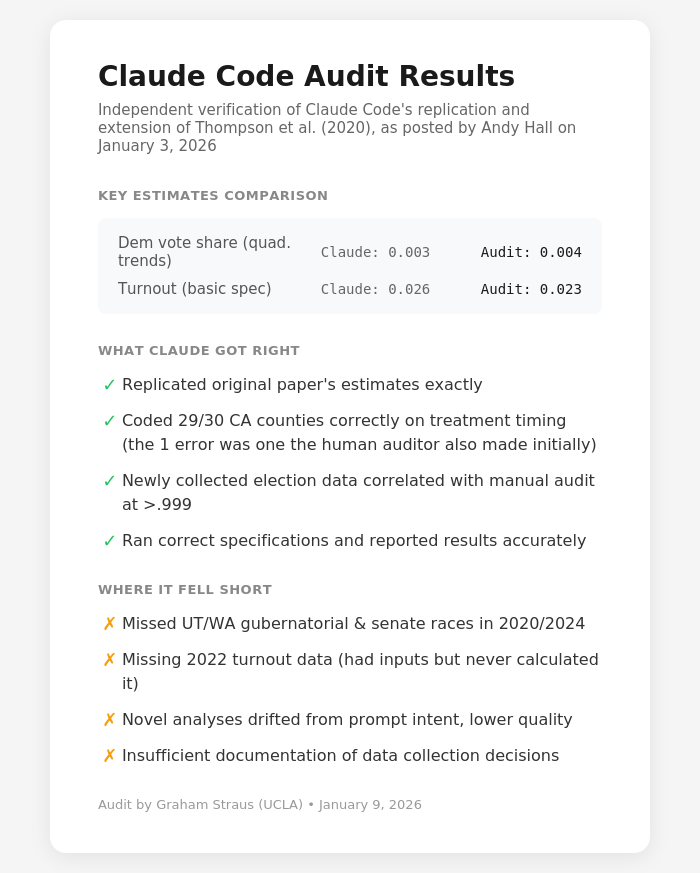

I’d been fiddling around with a version of this essay for weeks, ever since I started seriously using Claude Code with Opus 4.5, but recent demonstrations by Andy Hall have accelerated some timelines. His claim that Claude more or less one-shotted a paper replication in a weekend was perhaps exaggerated (this was a perfectly selected case and there was clearly a lot of prompt engineering that went into it), but that’s the way to actually make a point in contemporary information ecosystem. It’s an existence proof, and we’re going to see more like it.

From Andy Hall’s post.

Hall proposes some speculative applications of AI, serious possibilities that demand structural reform to implement. Automated replication (upon journal publication) is a no-brainer. This is something that LLMs really can one-shot, even now. I hope to see journals implementing this policy within the year.

In In Favor of Quantitative Description, the post that led to the founding of the JQD:DM, I wrote that:

In a complex and rapidly changing world, social science needs as many time series as possible.

This is precisely what Hall cites as a capacity afforded by AI. We no longer have an excuse to ignore the problem of temporal validity; we need to keep our knowledge up to date. Great! Genuinely, this is great, and we should do it.

But how? Getting this right isn’t a technical problem, it’s an institutional problem. This is why we need metascience, in this case a detailed economic/sociological understanding of the current institutional arrangement. Academia is both conservative and polycentric; our practices have evolved to serve a variety of different purposes, making optimization and reform very difficult.

Hall is unflinching in applying market logic to the situation: AI will proliferate, quickly, through the academic system because “The Economics Demand It.”3 He’s not wrong! There are hundreds of thousands of scientists who competing for a fixed number of positions. The stakes are high; do you get to live near your family? Do you get time to actually do the research you’ve devoted your intellectual life to? Do you get health insurance? At current prices, LLMs can be used to automate a large chunk of the grunt work of academic research, and we’re well past the point of returning to an equilibrium where no one uses them.

If we do nothing, we are going to be flooded. Both with low-quality slop, and with inane, precise, accurate papers; Hall is again correct in pointing to these two risks.4

Herb Simon’s famous quote remains essential:

What information consumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it.

This is the core role that academics must retain. We must refine our taste, our ability to filter through the information with which we will soon be flooded. Perhaps we’ve been flooded for decades, but the problem can always intensify. We simply need to spend more time reading, both old books and new forms of knowledge encoding, more time cultivating our own expertise; we now spend too much time producing knowledge.

I’ve long flirted with the idea that science should simply become a knowledge machine, that we should arrange ourselves as coal-stokers feeding the engine of science that spits out truths which no human mind can verify. This idea is seductive; it is the culmination of contemporary epistemic trends in quantitaitve social science. There are two main downsides:

How can we know if the knowledge machine breaks down?

The process of science doesn’t just produce knowledge; it also produces scientists.

Let’s be honest: as a social scientist, I believe in the value of expertise. Our societies will be worse off without social scientists, even if we are replaced by machines which are capable of producing “more” social science knowledge.

But the first concern is a political concern, and thus perhaps even more important. We can build the knowledge machine, but it really matters who owns the knowledge machine.

Democracy has been badly burned by the previous wave of outsourcing a core function to new media technology: social media was never a digital town square, and the democratization it promised in fact only accomplished a delegitimization of existing forms of epistemic authority with no valid replacement. “It would be ridiculous to refer to the electromagnetic field through which the message runs as a republic,” writes Flusser in 1985. Sure, the possibility frontier of what is possible with new technology is larger than it was before, but we need to acknowlege that it takes time for people to collectively hammer out the institutional arrangement that allows for healthy communication.

We eagerly abandoned the decentralized world of the blogosphere and RSS feeds for a platform which allowed us to quantify our cleverness and is now being used to generate unprecedented amounts of what amounts to child porn. Was that a good decision?

So, yes, the current situation with journals publishing static pdfs is indefensibly antiquated. But the current academic polyarchy is actually quite robust; the sluggishness, the institutional conservativism, is necessary for something to have persisted as long as it has.

So I’m opposed to jumping too quickly to radically new institutions reliant on corporate-controlled tech. The risks are too large. But neither can we afford to ignore the situation. We must be proactive in incorporating LLMs into the scientific process in a way that allows us to better serve our fellow citizens in the short rule while retaining our long-term epistemic capacities. If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.

Embarassing aside: when I was searching to find the exact quote I found out that it’s actually apparantly super famous? Oh well I already wrote the intro so the cliche stays. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Di_Lampedusa_strategy

For prediction enthusiasts: I’m calling this for the poli sci journals APSR, AJPS, JOP and BJPS, and for applications to the ERC panels SH2 and SH3. Hold me to this when the organizations post their

On this point, we see the lie of neoliberal ideology, that the optimand is human freedom. At the margin, of course, it’s correct that overthrowing existing dogmas and petty tyrannies provides more immediate options to act, but in equilibrium what emerges is a new kind of tyranny, of technocapital. The economics demand it, and we are powerless to refuse them. This is why I am a Beerian cyberneticist: in the current technological milieu, I believe that freedom must be designed.

I also agree with Hall’s concern, about an increase in p-hacking. The solution here is less institutional than it is epistemic: I believe that we must abandon the farce of hypothetico-deductivism and the associated bandaids of preregistration and multiple testing corrections. We need a credibility revolution for inductivism — the bitter lesson is that inductivism can work, and we need to harness this insight rather than re-thump our Logic of Scientific Discovery-bibles.

Lots of great thoughts here Kevin! In a world of AI slop it’s possible that the journals become more important rather than less, if they can become the trusted curators, but I agree they’ll need to change dramatically to pull that off.

Having research controlled by corporate AI systems—and more generally having thought controlled this way—is one of the single biggest problems that’s coming for the world. It doesn’t seem for now like open source AI is keeping up so we’re going to have to come up with other ideas for how to either keep AI decentralized when it comes to knowledge production (so we aren’t too reliant on a single model) or else make sure our preferences and values rule over the AI.

I’ve been thinking about how to do this and would love to discuss.

(Btw on my piece: there really wasn’t a lot of prompt engineering and I didn’t iterate at all. Claude wrote the initial prompt which is why it’s so well detailed)

The old adage, "Publish or perish" takes on a new perspective. With the ability to curate a portfolio, 'self appointed scholars' may more easily gain entry into positions which traditionally were earned over time invested producing reliable quality. A whole new way to 'fake it till you make it' has come into play. Without intentional efforts to direct an alternative course...all the slop will erode and obscure the purity of the institution.