Open Science and Its Enemies

Donald Trump has signed an Executive Order nominally aimed at “Restoring Gold Standard Science”. Setting aside the absurdity of “restoring” something that never existed, what does that purport to mean?

Gold Standard Science means science conducted in a manner that is:

(i) reproducible;

(ii) transparent;

(iii) communicative of error and uncertainty;

(iv) collaborative and interdisciplinary;

(v) skeptical of its findings and assumptions;

(vi) structured for falsifiability of hypotheses;

(vii) subject to unbiased peer review;

(viii) accepting of negative results as positive outcomes; and

(ix) without conflicts of interest.

It seems like someone in the Trump administration has been following the debate about how the “replication crisis” and reading op-eds in Nature about institutionally mandating the rules of sceince.

Somewhat counterintuitively, however, the “Open Science” reform community that had been publically excoriating science for not doing the things now (provisionally) mandated by the government is outraged.

Now, that’s a bit unfair. The recent press release opposing the Executive Order by the science reformers at the Center for Open Science is sober and productive. They are correct to note how much worse it is if the state is controlling scientific practice rather than leaving that up to scientific practitioners; I found this paragraph especially compelling:

The Executive Order does not provide any standards for non-scientific information. As a consequence, this Executive Order is positioning policymaking to ignore scientific evidence by holding it to unachievable standards, and to use ideology and non-scientific information by holding it to no standards at all. Responsible policymaking uses the best available evidence.

This is a horrible time for US science, with this latest executive order merely the latest manifestation of the brazenly cynical political power grab over one of our greatest achivements. I’m going to be somewhat critical of the science reform movement, but I’m confident that we agree that the current assault on academic freedom is a horrific overreach of far more significance that what I’ll discuss here.

A recent case from the history of scientific criticism and public demonization of science provides an illustrative parallel. The 90s “Science Wars” pitted scientific “realists” (who, broadly, believe that the phenomena which scientists talk about are “real”, necessary and objectively given) against the “constructivists” or “postmodernists” (who, broadly, believe that those phenomena are the result of social processes, contingent and subjectively derived).

The latter camp was obviously correct, at the margin. Through careful historical and sociological study, they traced the construction of those phenomena. The blithe faith that Science is a transcendent human endeavor and that all of the activites undertaken by (mainstream, credentialed) scientists is a necessary component of this transcendence does not withstand scrutiny.

As is inevitable with methodological fads, the constructivist critique became a victim of its own success. Bruno Latour notes, sadly, the seeming parallel between cynical climate change agnotologists and his own work as a scientific constructivist:

I myself have spent some time in the past trying to show “‘the lack of scientific certainty’” inherent in the construction of facts

It is far too neat to blame Latour and other constructivists for today’s climate denialism — if only academics had that much power! — but I think it is fair to say that they could’ve been more careful and less dogmatic. There is only so much criticism of Science (and Science-ism) the public can experience without questioning the value of the science (funding for academics) they actually pay for. And, in a common failure mode for any social movement, the constructivists became characterized by their most flamboyant members. Latour “punches left” at just such a figure

What has critique become when a French general, no, a marshal of critique, namely, Jean Baudrillard, claims in a published book that the Twin Towers destroyed themselves under their own weight, so to speak, undermined by the utter nihilism inherent in capitalism itself—as if the terrorist planes were pulled to suicide by the powerful attraction of this black hole of nothingness?

but this comes far too late. If the public sees the “Science Wars” as pitting the hard-nosed scientists who make planes fly against this kind of airy-fairy Fr*nch wordcel, it’s not hard to see where their sympathies will lie.

Like with the constructivists, the science reform movement begins with some obviously correct and valuable insights between how scientists mythologize their practices and the way science actually unfolds. And just as we shouldn’t blame Latour for the machinations of ExxonMobil or BP, it is unfair to pin the blame for Gold Star Standards on the science reform movement itself. But I think we can learn something about how to minimize potential backlash to science while still allowing for progress by paying attention to three elements of the science reform programme.

Too much public self-criticism

Science cannot be mandated

…especially not if the mandate is unfunded

On the first point, I blame Twitter more than any person in particular. It insinuited itself into our epistemic culture; we didn’t realize how to grapple with this new technology, and the COVID pandemic exposed cracks in our scientific communication apparatus.

The second point, however, is latent in the program of “Open Sceince.” The kind of scientific perfectibility aimed at in response to the “reproducibility crisis,” especially as it has spread from social psychology to include much of the quantitative social sciences, becomes too easily authoritarian. The requirement to remove discretion from individual scientists — to have methodological review boards, to bind our hands with preregistration, to remove “researcher degrees of freedom,” to have mandatory replications — implies that there will be someone doing the requiring. None of the reformers ever suggested that this enforcement would come from outside of the academic community — but confronted with the cynically applied power of the US federal government, this is revealed to have been a fragile equilibrium.

The final point seems more niche but is most directly related to the executive order. These “Open Science” mandates were rolled out but not funded, to use some jargon from a US Civics course. Individual scientists had to comply with these new rules, raising the resource and especially time cost for each new publication without any offsetting increase in pay or decrease in workload. The current Exective Order makes the problem dramatically worse, as we’re all being held to such high “standards” that essentially all of our time would need to be devoted to ensuring that we are in compliance.

Too Much Public Self-Criticism

Collins and Evans (2002) introduces the “Science of Expertise and Experience” and is hugely influential in contemporary sociology of sceince — and largely unknown to practicing scientists who stopped engaging with the philosophy of science with Popper. They seek a “third way” or rather a “third wave” of the study of science, moving beyond the hagiography of first wave science-lovers like Robert Merton and the potentially corrosive critique of second-wave postmodernists like Latour. Science, they argue, is a fallible social process rather than a quasi-religious practice that reveals The Truth, but it isn’t exactly the same as all other social processes and attendant knowledge claims.

Science, they say, should primarily be understood as expertise — we tend to focus on knowledge as the primary product of science, but (especially for science of immediate interest to the public as opposed to more esoteric “basic” science), the single most important product of science is scientists. We simply cannot extract all scientific knowledge contined in our precious peer-reviewed pdfs and feed it into a Decision Machine to tell us what to do; we need scientists with expertise in order to advise us on complicated questions of the application of scientific knowledge to social/political questions.

So a key part of what scientists do is only really of interest to science; we all acknoweldge that no single study is perfect, and that the process of refining scientific knowledge claims requires a lot of back and forth, debates, theoretical and empirical advances, before we can consider any scientific question anywhere close to settled. To able to be contribute to scientific debates at the frontier of knowledge, people require many years of study and experience; there’s no reason to think that lay members of the public have any standing to evaluate these niche theoretical claims or experimental evidence.

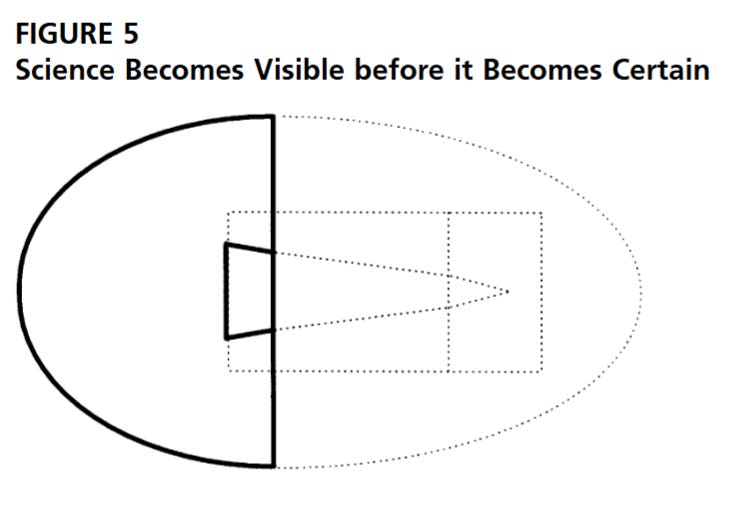

Collins and Evans outline a healthy unfolding of science, where scientists are able to do this crucial knowledge refinement work in private, and only then presenting a position to the public which is never unified but is at least vetted and stable. They also present the negative case: what happens when “science becomes visible before it becomes certain”:

But now [the public] finds that the scientists, who previously revealed a relatively united and robust front, argue with each other with different sides having rough parity; they change their minds, and are no longer a source of confidence. It is easy to understand why scientists prefer to keep their work private until they have reached something closer to unity.

The diagram is a bit baroque, in the tradition of science studies diagrams, but the intuition is simple: scientists need private spaces to refine their work before putting it out into the public.

The development of Science Twitter was, in view of this perspective, a huge mistake. Scientists were tricked by the logic of the platform into having a single, public-facing account where they did three very different kinds of things:

Had intense debates about the status of scientific research, often criticizing scientific practice.

Shared their own scientific findings with the public, towards the goal of “impact” so prized by today’s hiring committees and grant awarding institutions.

Spouted off about their private political opinions.

Each of these things is a perfectly reasonable thing to be doing — just not all of them, at once, from the same account.

The internet affords many new communication opportunities, but it’s essential that we figure out how to use the internet in ways that suit our individual and collective goals rather than the way that for-profit corporations have discovered best lets them sell ads. We seriously need to rethink our communication infrastructure and strategy in light of the internet, rather than just taking what these corporations offer us “for free.”

But Collins and Evans framework also makes it clear how catastrophic the COVID case was. In a recent blog post, the excellent Ben Recht says

Part of the mess we’re in now is because the pandemic response cast science, which is always a mess, as THE SCIENCE, which enforced policy. The federal science agencies in the US were not equipped for this task.

The enormity of the demand for information combined with the immediacy of the communication technology means that we all got to see “science become visible before it became certain.” COVID was unlike, say, nuclear energy regulation because everyone was immediately affected by it, and everyone had direct experience and thus possible expertise about it. Per Collins and Evans, this means that we should be democratizing decision-making and not deferring to experts. But everyone was affected by everyone else’s actions — a decentralized response seems like it would’ve been chaotic and far worse than we got.

COVID was a terrible stress-test of our scientific policy and communication system — and it’s difficult to believe that the previous decade of sometimes histrionic public self-criticism of science’s flaws didn’t soften the ground for the present mandated scientific straightjacket.

Overall, I think this angle is mostly an unfortunate confluence of Twitter and the pandemic that would’ve been difficult to avoid, even if we can and must do better with how we use the interent. But promoting the idea that science can be mandated is a more specific cause of the current mandating of science “reform” from the Gold Star fiasco.

Science Cannot be Mandated

The idea that “science cannot be mandated” (or, “anything goes”1) is exactly the opposite of the ideology of today’s most dogmatic strand of “Open Science” reform, which I called The Second Reformation in my article from last year:

“Open Science” is meant to make science more transparent, to break down the opaque and esoteric scientific process into discrete, verifiable chunks. Rather than cultivating unique, idiosyncratic scientists and their concomitant expertise, the “Open Science” approach aims to make practicing scientists more or less interchangeable cogs in a great machine of science. If your work is replicable, that means that other people can do it — and that, ex ante, we can set public standards for what methods count as “good science.”

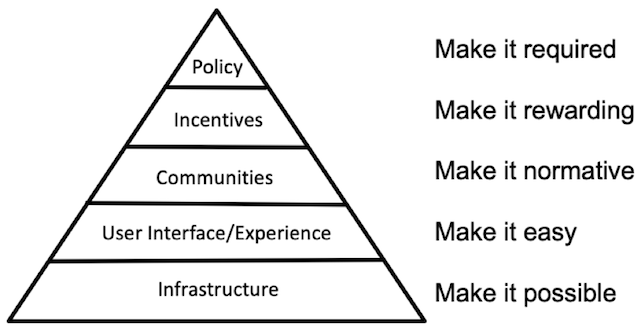

The approach to reform is far more authoritarian than that of the Trump adminisitration, but at the end of the day, there’s still the explicit goal of making elements of science required. This is the pyramad of culture change advocated by the same Center for Open Science who published the press release from the intro:

The bottom of the pyramid is entirely unobjectionable; this is how science should progress, developing tools and communities that make your preferred vision of science easier. This is basically what Latour describes as Science in Action: actions are transformed into “methods” the more they are black-boxed, the more that the scientific community comes to accept them as given in the course of research.

In the beginning, a paper using something like “pre-registration” requires a lot of citations for the procedure, explaining to potentially unfamiliar readers what it is and why they should trust it. Over time, as the procedure becomes more accepted, fewer citations are needed; eventually, once the idea can be presented on its own without citation, it has become a “fact” of the scientific process.

Notice, however, that Latour never talks about “facts” being required. If a community of scientists all agree on the process as a standard, stable method from their toolkit, no requirement is necessary; if that community doesn’t all agree, who would have the standing to decide what is required?

Well, Trump has decided that he has the standing. And that’s clearly bad. Worse, still, is that he’s cutting science funding while imposing these mandates, making them all unfunded.

….especially not if the mandate is unfunded

The “incentives” in the fourth tier of the Pyramid of Culture Change are not, unfortunately, financial: they have primarily taken the form of Open Science “badges” that signify that a given publication conforms with certain practices.

The resulting social pressure is a cost-effective way to promulgate norms — cost-effective, that is, from the perspective of the reformer, not necessarily anyone else in the system who decides to adapt to the changing norms.

The result, as Thomas J. Hostler writes in The Invisible Workload of Open Research, is

a clear danger that additional expectations to engage in open practices add to the workload burden and increase pressure on academics even further…It is argued that there is a high chance that without intervention, increased expectations to engage in open research practices may lead to unacceptable increases in demands on academics

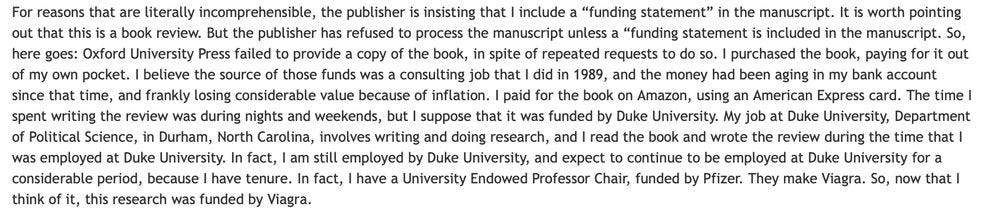

There is a non-zero administrative burden associated with every form of mandate. These have traditionally been imposed by universities (via IRBs, inane training modules) and by journals (checklists, mandatory COI or funding statements). For a recent and I think amusing example of the latter, here is a funding statement from a book review published by my dad:

These are all annoying and much of the effort is entirely wasted, but they were mostly unrelated to the process of science itself. In contrast, the journal-imposed mandates around computational reproducibility have been inserted in the middle of the publication process.

I’m not against mandatory computational reproducibility (and, more basically, open data/code) for a certain class of work; it does seem important to catch coding erorrs and to serve as a resource for future researchers. This all comes with a cost, though, one born by journals in addition to authors.

During the pandemic, I had the memorable experience of dealing with a computational reproducibility check which a journal had assigned to an undergraduate student. They were quite busy; they answered my email asking for an update on the reproducibility check by saying that it was on their to-do list but that they were currently “slammed with midterms.”

Making something mandatory but requiring undergraduates to magically develop superhuman time management for them to function properly is not a viable solution. In line with my longstanding concern with temporal validity, this approach treats the speed of publication as scientifically irrelevant — which, especially in the case of digital media, is obviously false.

The Trump Executive Order realizes Hostler’s prediction at a far greater scale than anyone could’ve forseen. Science and scientists are (apparently) to be held to a literally impossibly high standard through these proliferating and even mutually exclusive unfunded mandates.2 The fact that this is being done simultaneously with severe and arbitrary budget cuts makes clear that the goal is not in fact to improve the quality of science but rather to hamstring scientists.

My primary reaction to the Gold Standard Science Executive Order is a profound sadness. The specific policies are of course absurd. Worse, even if a more sane administration reverse the policies, this EO represents a ratcheting up of the politicization of science, something that is extremely difficult to undo.

But science will go on. As will sharply differing opinions about what constitutes good science, how we should be spending our energies. My hope is that the next round of this debate takes extra care to demonstrate to the public the value of what we scientists do — and that it recognizes the importance of scientific freedom in every particular of scientific practice.

Since this is so often misconstrued, let’s revisit what Feyerabend means by this. From Wikipedia: “In Feyerabend's words, "'anything goes' is not a 'principle' I hold... but the terrified exclamation of a rationalist who takes a closer look at history."[90] On this interpretation, Feyerabend aims to show that no methodological view can be held as fixed and universal and therefore the only fixed and universal rule would be "anything goes" which would be useless.”

These two points from the EO are basically mutually exclusive (v) skeptical of its findings and assumptions; (vi) structured for falsifiability of hypotheses. If we are skeptical of our assumptions then no test can falsify our hypotheses; they could always just be evidence that our assumptions are false. (YES, to the four of you reading this who care, this is a more general problem with falsificationism).

I can’t help thinking that this is a reaction to what happened during COVID more than anything else