Do Something Else

Lakens: I think I’m more a metascientist than a science reformer, I don’t really feel like a science reformer

Mehta: But you are, you cannot self-identify…if you have been making reforms or advocating reforms...doesn’t that make you a…

Lakens: Well, that’s a good question, let’s explore it for a second...we know there is waste in a system...I’m not advocating for anything I’m just pointing out some relationships…

Mehta: You’ve said it enough times that you think that people should be publishing everything they do I kinda don’t agree... (minutes 29:30 - 34:00)

I more than kinda don’t agree. Daniël Lakens is a radical activist. That’s not the problem. The problem is that his activism is universal. He wants to impose methodological rules on all of social science (and apparently Toxicology)—while denying that this is his goal and also denying the necessity of providing empirical evidence that these rules actually improve scientific practice.

I’ll begin by providing an example of Lakens’ philosophical incoherence, followed by an argument that we should think of the broader science reform movement spearheaded by Lakens as the “Second Reformation” rather than the “Second Renaissance”: they preach a purification of Science, that our salvation will come through works alone.

Following the success of diagnosing others as engaging in Questionable Research Practices (QRPs), I propose a novel QRP to describe how Lakens has engaged with philosophy of science. The reforms he has advocated are not, despite his repeated claims, “value free,” but rather embody the ideology of neoliberalism.

With this theoretical background, I discuss two case studies. The first, which inspired me to write this article, is his recent blog post “Why I don’t expect to be convinced by evidence that scientific reform is improving science (and why that is not a problem).” This post prominently but deceptively cites his article “The benefits of preregistration and Registered Reports,” recently published in Evidence-Based Toxicology (?!?), the abstract of which says “We review metascientific research confirming that preregistration and Registered Reports achieve their goals” (emphasis mine). This paragraph is already damning enough, but I’ll explain why it’s even worse than it looks.

The second case study involves the publication of Tal Yarkoni’s magnificent article “The generalizability crisis” and Lakens’ attempts to use arguments from authority to shut it down during the peer review process and then to discredit it after this proved unsuccessful. Yarkoni is a both a personal and intellectual hero of mine — he bravely took his own advice outlined at the end of the article, to do something else after realizing the limitations of academic psychology research.

The only intellectually honest position as a scientist is to entertain the possibility that you’ve found a dead end and that you should do something else. Perhaps you started down a path that seemed promising and may even have been the right direction for a time, but you’ve gone too far and there’s no more juice to be squeezed from the stone. All of us should consider this possibility. Including Daniël Lakens.

Francis Bacon and The True Induction

Despite his success in reforming social science practice over the past decade, Lakens maintains that he is not at all a reformer but merely a vessel for the movement of the sprit of Science through history. Practicing scientists have strayed from the true path laid out by the prophets Bacon and Popper—so Lakens and his fellow reformers want to lead them back into the light, which requires imposing stricter and stricter rules for how to conduct science.1

I sarcastically called the modern credibility/causality/replication/pre-registration movement “Science 2,” in a recent blog post on the incoherence of science reform. Apparently, some people are calling this “the Second Renaissance”—but the better term for the austere, dogmatic strand of science reform coming out of social psychology is the “Second Reformation.”

Lakens is the most visible and doctrinaire of these radical Reformers — again, while insisting on the pretense of objectivity, that he is simply following the inevitable logic of Science. His podcast is called Nullius in Verba—Francis Bacon’s phrase, meaning “take nobody’s word for it” — and the description notes that

Our logo is an homage to the title page of Novum Organum, which depicts a galleon passing between the mythical Pillars of Hercules on either side of the Strait of Gibraltar, which have been smashed by Iberian sailors to open a new world for exploration. Just as this marks the exit from the well-charted waters of the Mediterranean into the Atlantic Ocean, Bacon hoped that empirical investigation will similarly smash the old scientific ideas and lead to a greater understanding of the natural world.

This description is brazenly lifted from Wikipedia:

The title page of Novum Organum depicts a galleon passing between the mythical Pillars of Hercules that stand either side of the Strait of Gibraltar, marking the exit from the well-charted waters of the Mediterranean into the Atlantic Ocean. The Pillars, as the boundary of the Mediterranean, have been smashed through by Iberian sailors, opening a new world for exploration. Bacon hopes that empirical investigation will, similarly, smash the old scientific ideas and lead to greater understanding of the world and heavens.

Which, whatever, that’s just embarrassing. But what of the content of Baconian philosophy of science? Presumably Lakens’ decision to continuously invoke Bacon by using Latin to title all of his podcast episodes has a purpose besides causing our eyes to roll out of our skulls?

From Wikipedia (note how I’m citing my sources here):

In the first book of aphorisms, Bacon criticizes the current state of natural philosophy. The object of his assault consists largely in the syllogism, a method that he believes to be completely inadequate in comparison to what Bacon calls “true Induction”:

The syllogism is made up of propositions, propositions of words, and words are markers of notions. Thus if the notions themselves (and this is the heart of the matter) are confused, and recklessly abstracted from things, nothing built on them is sound. The only hope therefore lies in true Induction.

— aph. 14

In many of his aphorisms, Bacon reiterates the importance of inductive reasoning.

This sounds like it’s a podcast about the role of induction in science, and specifically about the slippery relationship between the words we use and the world we study—making claims like the “failure to take the alignment between verbal and statistical expressions seriously lies at the heart of many of psychology’s ongoing problems (e.g., the replication crisis).”

Whoops!

No, that last quote is from Yarkoni’s fantastic article on The Generalizability Crisis, which we’ll discuss in far more detail below. Lakens used anti-scientific arguments from authority (his own, and Popper’s) to try to prevent Yarkoni’s paper from being published.

Lakens adopts the aesthetics of Science, but it’s just for show. He simply does not have a coherent philosophy of science—Bacon and Yarkoni are saying literally, almost word-for-word the same thing, but Lakens idolizes one and demonizes the other.

I’d prefer to just ignore Lakens, as I’m not a psychologist and I don’t particularly care about the contortions of this other discipline. But the internet has allowed the Second Reformation to spread far beyond its birthplace — the holy practices they mandate have been imposed on related disciplines, and scientific practice in my field has been circumscribed by their demands.

I’m all about science reform — it’s the main theme of this blog, I have many ideas about how to make science better and I’m trying to persuade my peers to adopt those ideas. But persuasion is where to draw the line. Lakens wants to impose his reforms, across a diverse array of scientific disciplines he knows nothing about. He has accumulated a dangerous amount of power towards this goal, both institutionally and through his personal reputation for indefatigable bad-faith argumentation and being insufferable on every online platform on which social scientists discuss things. I’ve never met the guy, and I’d prefer not to make this personal—but his person has expanded so broadly across social science practice that it must be addressed.

The Second Reformation: Science Through Works Alone

According to the doctrine of the Second Reformation, the Church of Science has become decadent and complacent; the bishops are too obviously self-serving, the hierarchy too rigid. The people no longer believe in science; each new encyclical (“studies show”) is met with derision rather than obeisance. Just as Luther did a run-around of the Vatican with the new media technology of the printing press, the Second Reformation is powered by blogs, tweets and Pre-Analysis Plans.

The key principle of the Second Reformation is the inverse of that of the First Reformation. The establishment Church (Science) holds that we can only be saved and enter Heaven (produce Scientific knowledge) through a combination of faith (theory) and works (scientific practices).

Luther and his brethren felt that the Church’s insistence on the importance of works was simply a corrupt pretense to demand obedience and extract resources from terrified peasants. Nowhere in the Gospels does it mention the selling of indulgences or the existence of powerful cardinals holding the keys to Paradise. The Reformation preached the importance of faith alone — that regular people should be given direct access to the Bible and thus to God.

Lakens and his brethren, in contrast, feel that Science which gives discretion to individual scientists is simply a pretense to allow those scientists to smuggle in their own preferences and hide their lack of rigor. The Second Reformation preaches the importance of works alone — that scientific knowledge will automatically be produced if and only if scientists perform the correct rituals. Power analysis, replications, but most importantly, pre-registration. It doesn’t matter what the scientist believes; the primacy of works in Second Reformation theology is designed to prevent the contents of the scientist’s mind from having any impact on their scientific output.

The Second Reformation preaches the importance of works alone — that scientific knowledge will automatically be produced if and only if scientists perform the correct rituals.

I think this is absurd. I think there’s no reason to believe that this will make Science, writ large, better. But while I think that he’s wrong, I think that Lakens is perfectly justified in advocating for these reforms. Being a metascientific activist is great — with sufficient scope conditions.

The problem, again, is that his aspirations are universal. The doctrine of the Second Reformation has largely been adopted by the Nature portfolio, which plays an outsized role in setting the methodological agenda for all of the social sciences. See these guidelines for Nature Human Behavior.

Metascience is still a young field, and the Second Reformation is trying to strangle it in the cradle. Jupiterian philosophy of science has proven useless for informing social science practice, spurring a metascience that is bottom-up rather than top-down. Lakens hit on one particular reform — pre-registration — which makes sense in the specific context of experimental psychology. I say this genuinely: good for him, good for this subfield, well done. But he’s trying to jerry-rig a new, universal philosophy of science with pre-registration and associated procedures at its core.

The Demonology of the Second Reformation—and a New QRP

Conceding, with fervent agreement, that the established church of Science is decadent and corrupt, why must the Second Reformation take this form? The First Reformation wanted to use the new information technology to cut out the middleman, to go right to the source: divine revelation, the Word of God.

It doesn’t seem like divine revelation is a coherent foundation for Science. But the Second Reformation is propped up with gratuitous appeals to Church Fathers like Bacon and Popper and Meehl and Lakatos.2 These are incoherent appeals, but they provide the Second Reformation’s implicit answer to the famous Demarcation Problem: we know that Science is good and that we want to do it — but how do we know what Science is? How do we know if we’re doing it?

There’s a risk of thinking about this problem for too long; better to stay directly on the Popperian Path. Because once we start actually thinking about what we’re doing, we might find the devil lurking in the shadows — the great deceiver, whispering in the confused young scientist’s ear: “anything goes.”

Lakens, amusingly, attempts to exorcise Feyerabend with a technique that I believe to be novel in the history/philosophy of science. There are debates about how to interpret the texts of previous thinkers — should we consider all of philosophy as one ongoing conversation, or should we (like Rorty) simply take the words produced by the past as raw material for our own philosophizing? Lakens’ more radical approach — to reiterate, because it’s just so funny, he does this on an episode of a podcast titled Nullius in Verba — is to simply accept hearsay to redefine his historical antagonists’ philosophical positions:

in a conversation he [Meehl] can just explain something that Feyerabend or Kuhn never say, they never say “oh by the way we’re really mainly talking about physics here, so if you work in a different science then maybe you should not really take this stuff so seriously, it might not apply.” Those are observations they don’t write in their books, he presses them, and then you're like, oh that's kind of useful to know.3

We can’t simply accept that he meant what he, the professional philosopher, wrote in his books. You see, he must’ve really meant something else — it’s such a shame that we can’t have a conversation, to press him, to give him a chance to clarify his views. This is the historiography of the Second Reformation at the apogee of its power: the dream of dragging our philosophical opponents into court to repent.

For their contemporaries, the Second Reformation has identified several sins as Questionable Research Practices (QRPs). It’s a powerful of rhetorical move, to deem some Research Practices as Questionable. It both implies that other Research Practices are not Questionable — and that you’ll be the one doing the questioning.

So I think I’ll try my hand at it. In selectively citing philosophers of science, and in misrepresenting the views of the philosophers of science he does cite, Lakens is engaging in the QRP I call “Listening to Your Imaginary Friends is Not Good” (LYING).

Because that’s what’s going on. Bacon, Popper, Lakatos, Meehl, Feyerabend — when Lakens uses these words, he’s referring not to a philosophy or body of work but to his imaginary friends.

The problem with engaging in the QRP of LYING is that it makes it impossible to accumulate theoretical knowledge. I’m not accusing anyone of intentional wrongdoing, of course — the problem is structural: when we accept the central tenets of the Second Reformation, that Science is produced through Works alone, it doesn’t actually matter what we believe, or what we write in the parts of the paper that are unrelated to the Works we to preformed. This problem is compounded by the neoliberal commoditization of scholarship: individual scientists simply don’t have time to go back and read philosophy of science, to check that a citation is actually an accurate representation of what that philosopher said. And Open Science, I have come to believe, is neoliberal.

The Neoliberal Myth of Being “Value-Free”

Lakens presents himself as beyond ideology — he’s explicitly in favor of advocating for reforms only in the case that they make science work “more efficiently without any extra cost” or make it so “knowledge just flows in a less biased way through the network we’ve created…logically speaking not just a value judgement.”

This principle is the very definition of neoliberal ideology. Ideology functions here by being hidden, as portraying its vision for reshaping the world as natural, inevitable or at least unobjectionable. “Efficiency” is the keystone of this ideology: there’s no political tradeoffs to consider, we’re merely technocrats helping the system function more smoothly.

I would not have made the connection between Laken’s ideological mission statement and neoliberalism without Philip Mirowski’s provocative article on “The Future(s) of Open Science.”

Karl Popper, after all, was a member of the Mont Pelerin Society with Hayek and von Mises and the rest — by virtue of not being an economist, Popper usually escapes the association, but there really was an explicit intellectual organization where these guys all hung out on a mountain in Switzerland.

The paper is more than a bit paranoid, but the poetic validity of Mirowski’s thesis is in the pudding — Lakens explicitly endorses the ideology of neoliberalism as part of his larger political project of Open Science. Lakens’ position is that his meta-scientific activism isn’t activism at all:

What I think about when I try to improve the way people do science, I think that I’m improving the way we do our job, knowledge just flows in a less biased way through the network we’ve created and there’s just more transparency about things so we can evaluate thing better and all of that should lead to better knowledge generation, logically speaking not just a value judgement...the system just works better like this.

This is the core of neoliberal ideology: this isn’t politics, that nasty business where there are winners and losers, in which we admit to a vision of the world we’re pursuing.

The identification and excommunication of Research Practices deemed Questionable is not just a value judgment. Science just works better like this.

Metascience Through Logic Alone

But hold on a second.

Let’s be clear.

Science reform is not Science in the sense of testing hypotheses with data. When it comes to following the commandments of the Second Reformation, it is heretical to ask for empirical evidence.

Lakens recently published a blog post disavowing the possibility of empirical metascience. The thesis is that “evidence for better science is practically impossible.”

I find this post remarkable, for three reasons.

It’s another prime example of Lakens engaging in the QRP of LYING, this time about Paul Meehl.

He also somehow engages in the QRP of LYING about his own recently published paper that he quotes from.

He’s been working on empirical metascience for years.

I’m not the only one to notice that this blog post and the linked article are insane. Far more credible metascientists than I, like Mark Rubin and Jessica Hullman, have written far more sober responses than the one that follows. Lakens immediately responded to Hullman, but it’s more of the same tendentiousness and post hoc rationalization for the central role of pre-registration in the new philosophy of science.

Of course, we can’t restrict ourselves to what he writes — it’s more important to hear what he has to say when he’s pressed. This is why the quote that opens this article is so important. His longtime podcast cohost makes the same observation that any good-faith of observer of science reform would make: “You’ve said it enough times that you think that people should be publishing everything.”

I really want to dwell on this, because I believe it is evidence of a GEN-YOO-EYEN Kuhnian crisis in the paradigm of Open Science / The Second Reformation. This is in the same vein as earlier attempts by other science reformers to redefine the meaning of the dictionary word “replication” because it was leading to contradictions.4 We need to take a step back and really think about whether all of this makes sense.

Engaging in the QRP of LYING about Paul Meehl (warning: this one is a bit in the weeds)

In both the post and the linked paper he quotes in the post, Lakens cites Meehl’s 2004 paper “Cliometric Metatheory III.” Only Cliometric Metatheory III, mind you ; not Cliometric Metatheory I or Cliometric Metatheory II.

Lakens also takes the following potshot at Saint Paul:

In meta-science logical arguments are of the form ‘if we have the goal to generate knowledge following a certain philosophy of science, then we need to follow certain methodological procedures.’ For example, if you think it is a fun idea to take Feyerabend seriously and believe that science progresses in a system that cannot be captured by any rules, then anything goes. Now let’s try a premise that is not as stupid as the one proposed by Feyerabend, and entertain the idea that some ways of doing science are better than others. (latter emphasis mine)

Contrast this with Meehl (1992) — Cliometric Metatheory I:

Feyerabend’s much abused (because misunderstood) “anything goes” does not mean that one policy is on the average just as good as any other or that there is no optimal way to proceed at a given stage of a particular scientific development; rather it points to the fact that there is hardly a single rule, and clearly not a single guideline or principle, that has not on occasion been violated by a scientist or a whole group of scientists with resulting scientific success. (emphasis mine)

This is engaging in the QRP of LYING about Feyerabend’s thesis. “Anything Goes” is not meant to be proscriptive, but descriptive. The difference between Meehl’s (accurate) read of Feyerabend and Lakens’ stems from Lakens’ universal aspirations. Feyerabend might well agree that compared to the state of social psychology in 2010, pre-registration is the way to go. Feyerabend’s entire point is that it is unscientific to make a leap from that local, specific observation to a universal rule about what science is or how it should be conducted. We cannot say that pre-registered studies are better than non-preregistered studies in general.

But what exactly does Meehl say in the cryptic but apparently all-important Cliometric Metatheory III? Well, first, the paper is premised on a secret third philosophy of science — not deductivism or inductivism but Pragmatism, specifically the Peircean Consensus conception of truth:

The opinion which is fated to be ultimately agreed to by all who investigate...and the object represented in this opinion is the real. (quoted on p616 of the Meehl paper)

Contrast this with Lakens’ description:

[Meehl] proposes to follow different theories for something like 50 years, and see which one leads to greater scientific progress. If we want to provide evidence that a change in practice improves science, we need something similar…But we also need to collect evidence for a causal claim, which requires excluding confounders. A good start would be to randomly assign half of the scientists to preregister all their research for the next fifty years, and order half not to. (emphasis mine)

The bolded portion flies in the face of Meehl’s painfully detailed epistemology. The entire point of Peircean Consensus and the proposed 50-year period of “ensconcement” is a more “naturalized,” sociological account of scientific knowledge. Lakens gestures towards this premise and then jams in his own deductivist framework.

Meehl, obviously, doesn’t say anything about a 50-year RCT. The correct interpretation of his project is something like “Among the theories that have lasted 50 years, what can we learn about those theories that will allow us to come up with more theories that are also likely to last 50 years.”

Engaging in the QRP of LYING about his own paper

The linked paper is titled “The benefits of preregistration and Registered Reports.” So far, so anodyne. But then you notice that this is published in Evidence-Based Toxicology. Why, one wonders, is Lakens publishing in a Toxicology journal? Here’s the beginning of the abstract:

Practices that introduce systematic bias are common in most scientific disciplines, including toxicology. Selective reporting of results and publication bias are two of the most prevalent sources of bias and lead to unreliable scientific claims.

which perfectly illustrates my point about the promiscuity problem of the Second Reformation. This is what scientific universalism looks like. There’s no attention to the specifics of a given discipline — this entire article could be copy+pasted to literally any empirical scientific discipline. “Including toxicology” is a disparaging, throwaway disciplinary concession.

In fact, this is full-on metascience imperialism. Lakens is nailing his 95 theses (ok, ok, there’s actually only 8 self-citations) into fucking toxicology journals. The References reveal just how shallow the disciplinary engagement is. Of the 142 citations, only two of them are to journals with “toxicology” in the title.

Now, the rest of the abstract of the linked paper:

We review metascientific research confirming that preregistration and Registered Reports achieve their goals, and have additional benefits, such as improving the quality of studies. We then reflect on criticisms of preregistration. Beyond the valid concern that the mere presence of a preregistration may be mindlessly used as a proxy for high quality, we identify conflicting viewpoints, several misunderstandings, and a general lack of empirical support for the criticisms that have been raised. We conclude with general recommendations to increase the quality and practice of preregistration. [emphasis mine]

Hoolllllddd up there cowboy…“Confirming”?

Really?

The avowed Popperian falsificationist is:

A) “confirming” his theories

B) with empirical evidence?

A slip of the tongue, perhaps — but that’s the thing with these QRPs, when all the errors are in the authors’ favor you begin to wonder…

The second emphasized passage is more important: “there is a lack of empirical support for the criticisms of preregistration.” What follows is the only passage from the paper quoted in the blog post:

It is difficult to provide empirical support for the hypothesis that preregistration and Registered Reports will lead to studies of higher quality…[incorrect interpretation of Meehl]…Because such a study is not feasible, causal claims about the effects of preregistration and Registered Reports on the quality of research are practically out of reach.

This passage makes it sound like the entire paper takes this anti-empirical stance. But as we saw above, the abstract of the paper says that they “review metascientific research confirming that preregistration and Registered Reports achieve their goals.” The paper is incoherent — and when Lakens cites the paper in his blog post, he cites this single paragraph that contradicts the entire point of the paper.

Of course, this newfound anti-empiricism is not granted to anyone critical of preregistration:

There is no empirical evidence to support this hypothesis [that preregistration precludes exploratory analysis], and one could just as easily hypothesize that preregistration will help liberate exploration and give it its proper place in the scientific literature…Future metascientific studies should examine whether preregistration increases or decreases exploratory analyses.

Again: these two quotes are from the same, published paper! But only the first quote, the anti-empiricist one, makes it into the blog post. QRP.

Working on empirical metascience for years

Lakens has been busy, doing empirical metascience for years. On his blog, podcast, Twitter, and published research, there’s a lot of it. And I think it’s good! I think it’s interesting and well done! I’m a huge fan of empirical metascience!

But all of that work makes this abrupt disavowal of the possibility of empirical metascience extremely mysterious. This post is way too long so let’s cut to the kicker — I’ll just reiterate that Lakens’ about-face is an empirical puzzle, especially after the triumphal publication in Nature Human Behavior (by others in the Open Science movement) finding that “High replicability of newly discovered social-behavioural findings is achievable.”

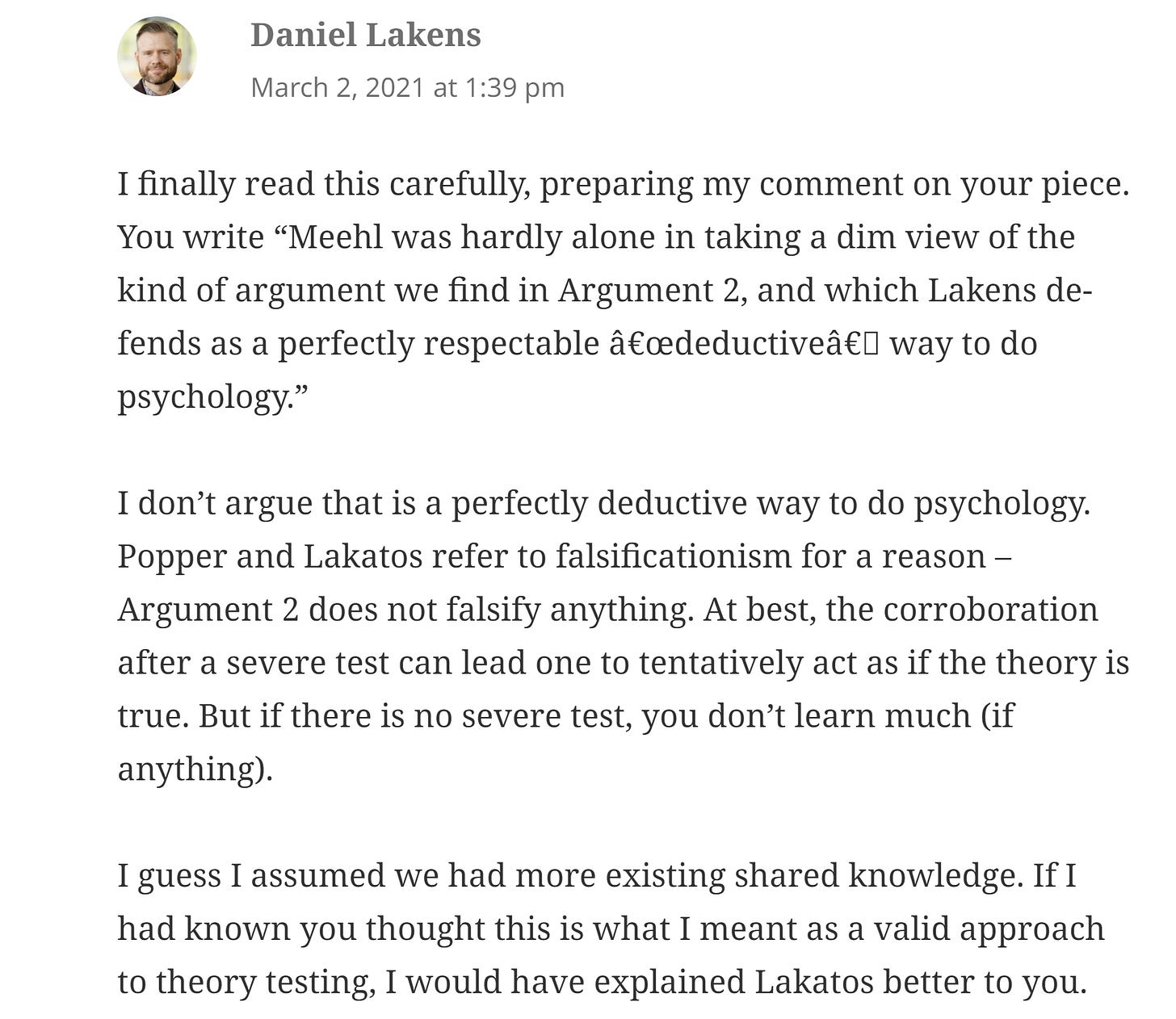

“I Would Have Explained Lakatos Better to You”

Let’s return to Bacon, Yarkoni, and Lakens. This is a pivotal exchange in the history of social science reform—and it illustrates Lakens’ approach pretty well.5

The exchange begins when he publicly posts the peer review he had submitted for Yarkoni’s paper on The Generalizability Crisis. Yarkoni responds on his own blog.

There’s a lot of moving pieces, so let me be clear: this is the most severe intellectual takedown I’ve witnessed during my professional career — and I’ve read a lot of blogs.

Lakens’ philosophy of science, as expressed in the review, genuinely seems to be justified according to the following syllogism:

There are two philosophies of science: deductivism and inductivism.6

Karl Popper says that inductivism is impossible.

Therefore, we must do deductivism.7

We must do deductivism. We must re-organize all of science towards the execution of “severe tests.” Why, exactly? Oh. Because Karl Popper said so.

Lakens’ review is nearly five thousand words long — and fifteen of those words are “Popper.” As in Karl Popper. As in

“You don’t need to read Popper to see the problem here”

“I am personally on the side of Popper and Lakatos”

“the article is a nice illustration of why philosophers like Popper abandoned the idea of an inductive science”

“This approach to science flies right in the face of Popper”

“If we read Popper…we see induction as a possible goal in science is clearly rejected”

and, my personal favorite (remember — Nullius in Verba!)

“I would also greatly welcome learning why Popper and Lakatos are wrong”

Now, the References section of the review doesn’t actually cite Popper, and there are only two direct quotes sprinkled in. As for Lakatos…we’ll see that Lakens is engaging in the QRP of LYING.

Yarkoni points out that Lakatos never even considered the possibility that his framework would apply to social science. Indeed, Yarkoni cites a rare instance in which Lakatos considers the social sciences (italicized text is Lakatos’):

This requirement of continuous growth … hits patched-up, unimaginative series of pedestrian “empirical” adjustments which are so frequent, for instance, in modern social psychology. Such adjustments may, with the help of so-called “statistical techniques” make some “novel” predictions and may even conjure up some irrelevant grains of truth in them. But this theorizing has no unifying idea, no heuristic power, no continuity. They do not add up to a genuine research programme and are, on the whole, worthless1.

If we follow that footnote 1 after “worthless,” we find this:

After reading Meehl (1967) and Lykken (1968) one wonders whether the function of statistical techniques in the social sciences is not primarily to provide a machinery for producing phoney corroborations and thereby a semblance of “scientific progress” where, in fact, there is nothing but an increase in pseudo-intellectual garbage. It seems to me that most theorizing condemned by Meehl and Lykken may be ad hoc. Thus the methodology of research programmes might help us in devising laws for stemming this intellectual pollution.

….Some of the cancerous growth in contemporary social ‘sciences’ consists of a cobweb of such [ad hoc] hypotheses.

There are two possibilities:

Lakens “greatly welcomed” this passage because he learned that Lakatos was wrong.

Lakens continues to think that Lakatos is right, and that quantitative social psychology is “worthless…intellectual pollution.”

But we need to remember that Lakens isn’t actually interested in what these philosophers have written...if we could only drag them in here and press them, we’d find that their true thoughts aren’t written down anywhere.

Yarkoni is on the right track here in his response:

“I suspect Popper, Lakatos, and Meehl might have politely (or maybe not so politely) asked Lakens to cease and desist from implying that they approve of, or share, his views.”

“Now, I don’t claim to be able to read the minds of deceased philosophers, but in view of the above, I think it’s safe to say that Lakatos probably wouldn’t have appreciated Lakens claiming to be “on his side”

Laken’s next move is astonishing. Passive-aggressive, idiotic and yet impossibly self-assured. Ten months after Yarkoni’s response, in a comment on the blog post, Lakens writes the following:

My guy has just had devasting quotes from one of his Imaginary Friends thrown in his face — the entire enterprise of statistical social science described by Lakatos (one more time, for fun) as “pseudo-intellectual garbage” and “intellectual pollution” — and he returns, ten months later, to write that he regrets assuming that Yarkoni knew what he was talking about…that Lakens otherwise “would have explained Lakatos better to” Yarkoni.

I can’t imagine writing this sentence, in public, after being so comprehensively eviscerated, in a fight that I had picked by publicly posting my peer review in which I transparently attempted to use appeals to authority to shut down a paper.

Perhaps I’m needlessly hung up on this. I guess “I would have explained Lakatos better to you” is optimized to make my head explode. But why, exactly, did Lakens post this — and why did he wait ten months to do so?

My guess is that, by this point, it had been clear that Yarkoni was leaving his tenured faculty job at UT-Austin to take a job at Twitter. He took his own advice: “Do Something Else.”

This is an incredibly insightful and pragmatic update of “Anything Goes.” There is absolutely no guarantee that anything academic social scientists do will produce useful/valid knowledge. There’s no guarantee that the entire bloated eminence of PhD training, peer review, meta-analysis, and now pre-registration is worth it. It must always be possible that we are better off doing something else.

In fact, if we take Meehl’s Cliometric Metatheory III seriously, there’s a case to be made that quantitative social psychology is simply a mistake. It’s been the requisite 50 years since Lakatos called the discipline “pseudo-intellectual garbage.” What are the theories which have become ensconced? They had a bunch of theories — but over the past fifteen years they decided those theories were mostly made up and that they had to start over. Perhaps we’re better off cutting our losses and moving on.

Seen in this light, preregistration is ideal technological solutionism: “don’t worry, everyone, we agree that there was a problem but we’ve got it under control, this one simple trick means that we should all still keep our status and public funding.” But it’s always possible that the problem is deeper, that we should do something else. Perhaps even you, the social scientist reading this, should do something else.

Crucially, however, I am not arguing that some powerful entity should come in and shut down or radically re-organize social psychology. That kind of metascientific imperialism, of ruling out certain ways of doing things or of issuing commandments about how other people have to do things, is off the table. Indeed, it’s the only thing that’s off the table. I admit that I used to engage in these kinds of fantasies of power and control; some of my earlier metascience posts on this blog, certainly, had those ambitions. But this was a mistake, born of the hubris of knowing too much about one thing and not enough about everything else.

There’s nothing wrong with being an activist. Science is a social process; meta-science is a scientific social movement, as a recent sociology of science paper puts it. It’s normal and even laudable that scientists have opinions about best practices and that they try to persuade their colleagues to adopt the practices they think best. Indeed, for all the criticisms, I give Lakens full credit for genuinely caring about science. There are thousands of senior academics complacently enjoying the perquisites of plumb positions acquired in a different era, opposing any kind of science reform on the grounds that they find it personally inconvenient. Give me a radical activist like Lakens over Boomer deadwood any day—he’s at least wrong.

But wrong he is.

Metascience and science reform is much, much bigger than preregistration. With the internet and There is no scripture. There is no reason that we have to accept literally anything about the current institutional and sociological arrangement. The Second Reformation promises to make social science easy and failsafe, through Works alone.

But social science is hard. Nature does not own us any explanations. There’s no guarantee that any specific theory or method will yield results. The essential truth of science is that anything goes.

From the Wikipedia page about John Calvin: “He often cited the Church Fathers to defend the reformed cause against the charge that the reformers were creating new theology.”

For example, I just opened Lakens’ Mastodon page…the first post was a retweet of a picture of a bust of Karl Popper and the third post was a Popper quote.

Fuller quote (I transcribed this myself…transcribed speech always looks silly when written down, but I tried to capture the whole thing accurately):

"Feyerabend just admits that he's right...he's like yeah, when I talk about theory-infected claims I mean cosmological statements, so he means things are theory-infected when a physicist says how the universe works. And those things we can only observe with things that are also part of this universe...so, physical devices to measure physical things so then if the physical device is also part of your theory, then everything is theory infected. But he just says, fine, no, no, in psychology it's not the case, it's fine, Feyerabend just agrees...and I was like...wait what? He just agrees? And Kuhn was also a physicist so they're just talking about physics so this is not relevant to what psychologists do. And he naively explains of course psychologists do, you know you have a theory you design a certain experiment...that's influenced by your theory and what you want to figure out and other people with different theories would do different research but in the end we all just make observations...but anyway this point that in a conversation he can just explain something that Feyerabend or Kuhn never say, they never say "oh by the way we're really mainly talking about physics here, so if you work in a different science then maybe you should not really take this stuff so seriously, it might not apply." Those are observations they don't write in their books, he presses them, and then you're like, oh that's kind of useful to know…[gap]…getting this extra piece of information which Feyerabend never wrote down anywhere, but you know it's nice to hear about."

from my paper “Temporal Validity as Meta-Science”: Indeed, this problem has become sufficiently self-evident that social scientific reformers in other disciplines have resorted to redefining the word “replication” in order to square the reality of social science with the naturalist tradition. Nosek and Errington (2020) argue that the “common understanding...of replication is intuitive, easy to apply, and incorrect.” Instead, they assert that “Replication is a study for which any outcome would be considered diagnostic evidence about a claim from prior research.”

This rhetorical move may lead to better scientific practice by sidestepping sometimes tedious debates about whether one experiment is “similar enough” to another to count as a replication, but it requires giving up on the agnostic approach to external validity entirely. This conception of replication represents a radical re-routing of the social scientific process through the intuitions and judgments of social scientists. Indeed, I argue that this brazen re-definition is evidence of a paradigm in distress (Kuhn, 2012).

I wrote about this in a blog post Against Replication two years ago — but it’s relevant enough to expand on here.

Note that this premise is simply false. We’ve discussed Pragmatism above, and this third philosophy of science is experiencing a well-justified resurgence. Far more serious political science methodologists than I have recently written a magnificent account of the prevalence of abductive reasoning or “Inference to the Best Explanation” in the Journal of Politics. If you’re into arguments from authority, these are the incoming President of the Society for Political Methodology and the editor of Political Analysis.

Note that this is a logical fallacy.

Icing on the cake of this absolute banger of a post is the paper “High replicability of newly discovered social-behavioural findings is achievable” was retracted today.

That was a fun read! I learned lots of new names--including this guy Lakens.

But I have a different question: you use Phillip Mirowski's paper to argue that open science (at least the one organized through pre-registrations and open data) is neoliberal. But I guess my question is: so what? If I remember Mirowski's paper right, he seems to imply that Wikipedia is neoliberal (and by his definition, it is) and that is somehow a bad thing (because substantive expertise something something neoliberal something something). But I think, neoliberal or not, a world with Wikipedia is better than a world without it. So, while I agree with you that we don't want all the sciences to adopt one particular regime of open science, what's so wrong if it is neoliberal?