AI as Normal Science

shoutsout to Arvind and Sayash

Next week I return to my highly polarizing blogging about antimemes and media theory. Today we discuss the impact of AI on my day job as a computational social scientist.

In the spirit of Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor’s essential intervention into the breathless AI discorse, AI as Normal Technology, I want to share three ways in which LLMs and AI more broadly have intersected my research as a political scientist studying digital media.

These are modest contributions. But they are, I think, real. Surveying the past 2.75 years, since ChatGPT was released, there has been a huge amount of social science research of the form, “Hey Look, ChatGPT Can Do This!” or “No, ChatGPT Can’t Do That.” Very little of this research is relevant today, even sixth months later; the knowledge decays to zero too quickly.

Much of my metascientific theorizing is about setting the academic agenda. After watching several, accelerating hype cycles around digital media, I continue to think it essential that we bring more rigor to the question of What questions should we ask? The answers are only as good as the questions. And if the questions take the form of, “Is This NYTimes Oped True? We Spent 3 Years Designing A Rigorous Research Strategy And We Think The Answer Is…Probably Not But Maybe A Little”, or “We Beta Tested This Corporation’s New Digital Product For Free,” we have no hope of making scientific progress.

The temporal validity issues that I have been screaming about in the study of digital media are radically accelerated when it comes to LLMs. Try to submit an article evaluating, say, the ideological bias of a given LLM. Spend the bare-minimum 6 months from concieving the article to sending it out for peer review; enjoy the reviewer saying, “Oh but I read on X that the new version of this model is better.” And the reviewer isn’t even wrong! It’s the institutions of academic knowledge production that are the problem.

So, my three complementary contributions. A peer-reviewed study of how academics understand AI vs Machine Learning (ML), an updated policy about studying LLMs in the academic journal I edit, and an essay in the latest issue of the APSA Experiments Section Newsletter.

Thanks to a grant from the Penn State Center for Socially Responsible AI, my colleague Sarah Rajtmajer and I set out to study how academics understand “AI” and “ML” in their research. Our paper, Social Scientists on the Role of AI in Research, has recently been accepted for publication in the 2025 proceedings of the AAAI/ACM AI, Ethics, and Society Conference (AIES).

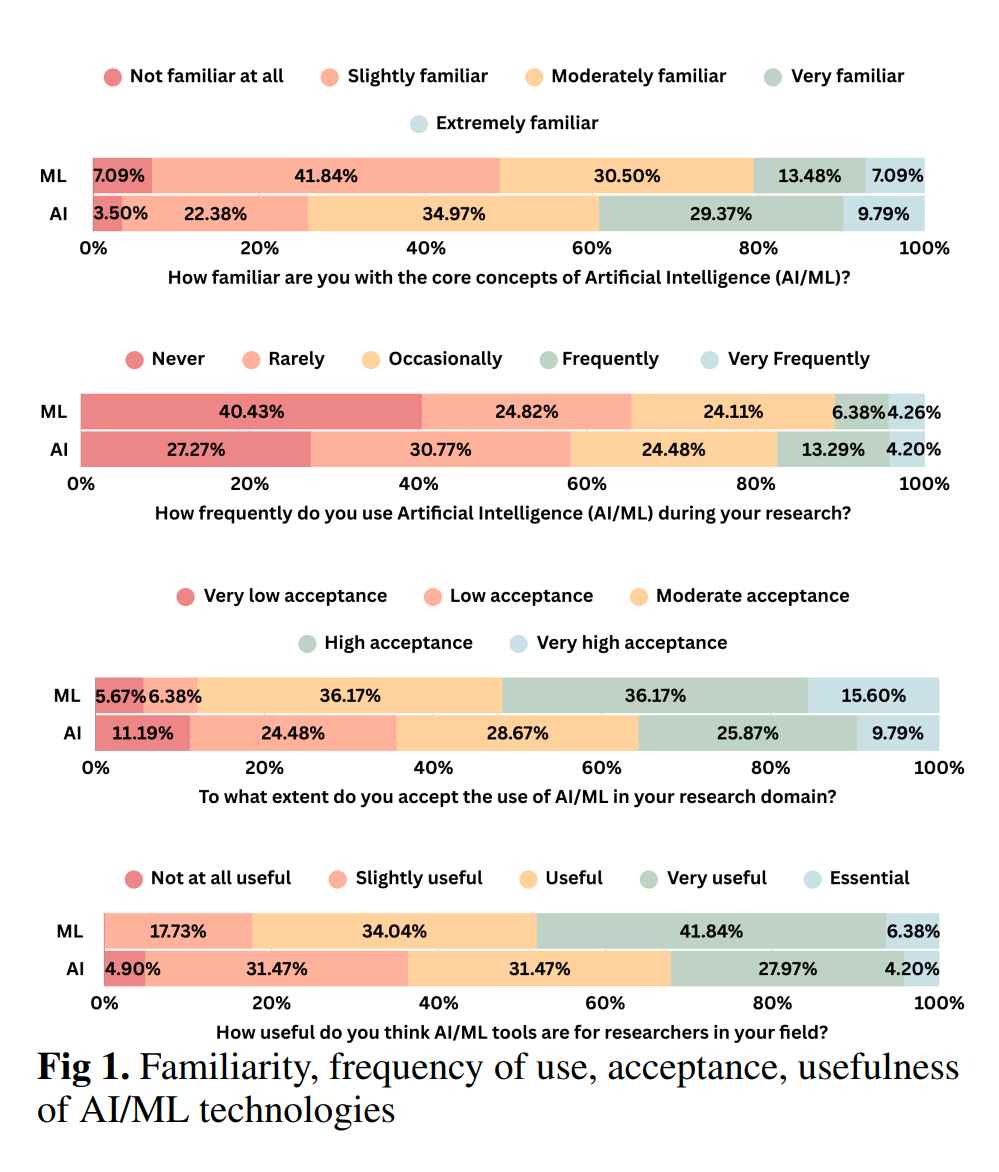

This research was directed Sarah and her team of grad students, who did an amazing job with the qualitative interviewing and coding the quantitative results. My role in the study involved a survey experiment: we asked respondents a series of questions about their use of AI/ML technology, but we randomized each subject to get the exact same questions about either AI or ML, throughout the whole survey. Topline results are striking:

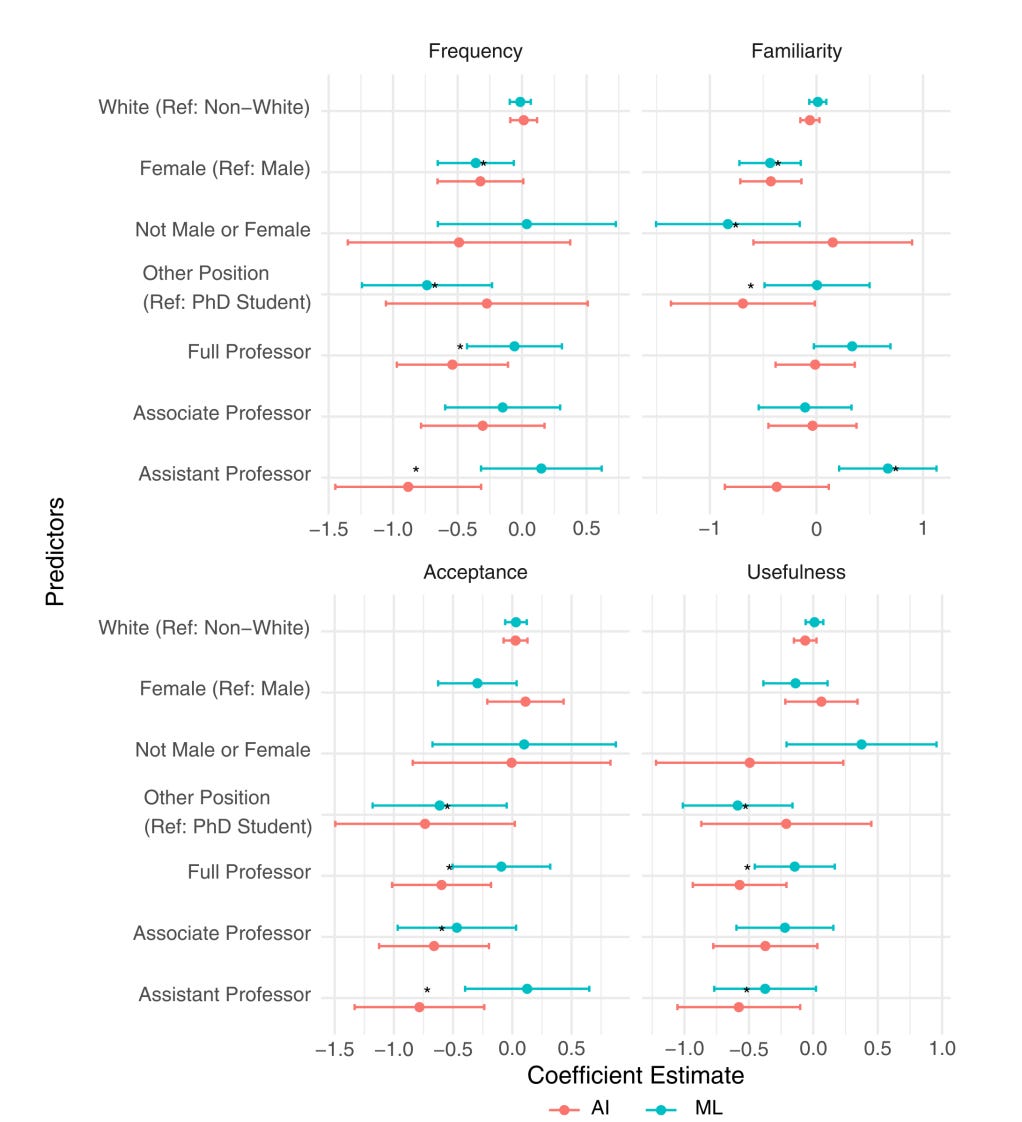

Perhaps even more interesting are the descriptive correlates of the answers to these four questions. Each coefficient should be read with respect to the reference category specified on the Y-axis, with a * signifying a significant difference. So, for example, in the top left panel, we see that female academics use AI significantly less frequently than do men — the magnitude of the coefficient is similar for ML, as well, but the comparison falls just short of significance. Women are also significantly less familiar with both AI and ML; we find no differneces around race.

The most striking results, to me, have to do with the interaction between academic seniority and these two different technologies. PhD students use AI significantly more frequently than either Assistant or Full Professors — but they are significantly less familiar with ML than are Assistant Professors (and, almost, Fulls).

The largest magnitude effects have to do with Acceptance — PhD students are significantly more likely to accept the use of AI in their research domain than are all three levels of Professors. This is mirrored in their estimates of the usefulness of AI — PhD students report it to be significantly more useful than either Full or Assistnat Professors. There are no differences by academic rank on any of these two estimates (of acceptance or usefulness) of ML.

These specific quantitative results are, of course, of limited temporal validity. What enhances their value is their combination with a series of semi-structured interviews that allow us to understand what our survey partipants actually think about these technologies. There’s a ton of insights in the paper, so I’ll just share my favorite quote here:

Hype chasing is a major issue because it “sucks the oxygen” out of the room in terms of resources and time. Furthermore, it enables bad actors to plug up publication pipelines with garbage. Not to mention generative text and images are changing the incentive structures of producing content online – it will be very difficult to find content actually produced by people who care about the content next to a mountain of botshit. – AI Survey

The area of social science over which I have the most control is the academic journal I co-edit, the Journal of Quantitative Description: Digital Media. Given our topical focus on digital media, we have needed to figure out to deal with the wave of studies about LLMs that looms over the next few years. After deliberating over the summer, we have established our standards for studies about LLMs. The full policy is here, including our position on the use of LLMs by reviewers, but I want to highlight a passage that illuminates the key issues we debated.

We are interested in quantitative descriptions of how LLMs are used, experienced, or integrated into digital communication environments. Relevant topics may include, but are not limited to:

*Patterns of LLM usage on social platforms, in content creation, or in communication workflows (more broadly, survey data about how people are using LLMs).

*Descriptions of user behavior when interacting with LLM-based tools (e.g., analyses of observational data from user engagement with chatbots, AI companions, writing assistants, or search engines).

*Or, conversely, user-based descriptions of the output of LLMs as a form of digital media, e.g. trace data studies of the media content produced by LLMs in response to actual user inputs.

This is the positive part; these are the kinds of studies we actively really want to see being conducted. This is is what we mean by AI as normal science—in the field of digital media, LLMs provide a novel modality by which citizens encounter information online. We want to start answering normal social science questions:

Who are these people?

How do they interact with LLMs?

What information do LLMs provide to these people’s interactions?

How is content hosted/generated by LLMs circulating around other parts of the internet?

These are very important questions! Moreover, they treat LLMs seriously but not as a something that we intrinsically care about. If the LLM generates something in response to an artificial, researcher-generated prompt, we don’t care about it — unless we understand which real people might be seeing that response.

We’re trying to get out in front of what I will have to say was my least favorite type of submission to recieve at the JQD over the past four years: “We Scraped Some Tweets and Ran a Topic Model.”

The sampling frame is usually under-specified

The justification for studying Twitter was usually not explicit; the true motivation in practice was that “it’s trendy” and then that “it’s easy”

The inductive nature of the model means that it will always produce something, with few safegaurds to understand if that something is meaningful or stable

So I don’t want to be reviewing a bunch of papers of the form “We Asked ChatGPT Some Stuff, Here’s What It Said.” I don’t care if it said something similar to what humans might have said; I don’t care if it said something different from what humans might have said. If the only humans to read the output are academic researchers, I personally don’t care about it1, and it doesn’t meet our criteria as interesting qua digital media. It’s fine for computer scientists or linguistics diagnosing algorithms to care about it, but that’s not what the JQD:DM is about.

We have an exception, where we’re thinking of LLMs as a form of recommendation algorithm.

LLM “audits” will only be considered if they have a significant cross-model or (ideally) geographical or over-time component. That is, there must be some real world variation of interest. This Google Search audit is an example of a minimal variation we might consider for an LLM audit: https://journalqd.org/article/view/2752

If researchers can control the LLM interaction process in a way that mirrors important variations in how humans might use those LLMs, we’re interested. I’m personally the most interested in the over-time component. Rapid progress in the field makes it absurd to publish the cross-sectional results of an LLM audit; the temporal validity is too low.

So, if you’re interested in doing research about LLMs along the lines we encourage, please send us an LOI! We just returned from our summer hiatus and we’re back in business at https://journalqd.org/loi.

Finally, in the Poli Sci corner, the second edition of the APSA Experiments Section Newsletter I co-edit with Krissy Lunz Trujillo has just been released. There are section announcements for the upcoming APSA meeting, for those interested, and five essays about experimental sample concerns across different types of recruitment methods.

My essay summarizes recent developments in the cat-and-mouse game of making sure that online respondents in surveys and survey experiments are real people, with the actual demographic characteristics they report, paying attention. We’ve developed many kinds of attention checks and tricks; survey respondents, mostly just trying to make money, have developed work-arounds. And now they can use LLMs.

A report from May 2025’s meeting of AAPOR, summarized in this blog post, demonstrates how serious the problem is. To reproduce their bullet points:

Operator successfully answers all the most common types of survey questions

Operator is very good at image recognition

Operator makes honeypot and prompt injection questions obsolete

Operator passed all the attention checks [they] included in the study

Operator will be consistent over the course of an interview

If you directly ask Operator if it's an AI or a human, it will lie to you every time

So…how about those attention checks?

There’s more in the essay, but this is the part I find most interesting:

Thinking meta-scientifically, social scientists must follow the lead of computer scientists in “establishing baselines and ongoing measurements.” The rapid progress in the development of AI tools like LLMs was only made possible by the field’s adoption of “frictionless reproducibility,” in the term of Donoho (2023): “The emergence of frictionless reproducibility flows from 3 data science principles that matured together after decades of work by many technologists and numerous research communities. The mature principles involve data sharing, code sharing, and competitive challenges, however implemented in the particularly strong form of frictionless open services.”

Political scientists have embraced the first two tenets; we would do well to consider the public competitive challenges (the “benchmarks”) whenever appropriate. But institutional reform is both the most important and most challenging step. In the age of LLMs, the validity of attention checks and specific online survey providers are methodological inputs that must be understood to drift, across time, at a faster rate than we can publish papers. Bare-bones open-source accounts of relevant subject attention and survey provider diagnostics give us a better chance at keeping up.

Well, I confess that I find it funny when LLMs say ridiculous things.

Yes, yes. Very responsible, this actual social science stuff you do. Now get back to work writing those McLuhanesque pronouncements that will lead you to fame and fortune, while making the genealogy of cybernetics the new hotness for social theory.