Discover more from Never Met a Science

There was a recent academic Twitter debate was over the question of paying invited speakers a fee ("honorarium") for giving a professional talk at internal departmental seminars [call this Q]. There are reasonable arguments on both sides of the topic, and because we are academics who are accustomed to setting aside ego and petty grievance in favor of the collective pursuit of knowledge, these arguments were heard, their merits weighted, and a consensus reached.

And if you bought that, I have a new crypto asset called "bridgecoin" I'd love to sell you.

The specifics of the debate matter because they illustrate both how social media changes the process of communication and the actors who can participate in it.

Academia is incredibly unequal. The resources, support and job requirements of a tenured professor at Harvard are in a different universe than those of an adjunct at a no-name university. More broadly, for the academics on the right side of the class divide (tenured or tenure-track at wealthy schools, of which I am certainly one), giving an invited talk is a standard part of the job and is generally considered both an honor and an opportunity for networking/getting feedback. We have sufficient resources that sharing our abundance like this is a pleasure, a way to deepen community bonds and create spaces for the informal creativity that is the lifeblood of scientific progress.

This is an example of what David Graeber calls "everyday communism," which he thinks exists both among pre-capitalist peasants and today's elite. The market provides reductions in transactions costs among a large number of interchangeable economic actors, but these transactions costs can be lower still (perhaps even *negative*) among groups with mutual trust and long time horizons. In addition to being grotesquely inhuman, a fully commoditized family household where each contribution is tracked and tallied is less efficient than the human practice of goodwill and mutual support.

From this perspective, the payment of an honorarium is like insisting on paying for half the groceries after a senior colleague invites you over for dinner: a gauche insertion of bean-counting where none is needed and an implicit *rejection* of the generalized reciprocity that governs these social exchanges. Given the bureaucratic overhead involved in institutions making payments to non-employees, paying honoraria would be akin to an enclosure of the academic commons, destroying an efficient emergent process (see: Elinor Ostrom). The most in-demand academics might make a few extra thousand dollars a year; that is, the rich would get richer. Indeed, a cynic might point to the reciprocal payment of honoraria within a small circle of rich academics as explicitly corrupt, a quid pro quo arrangement to launder the Department’s money to line their own pockets.

Outside of the privileged bubble, academic work (and indeed an increasing percentage of life) already resembles the world of total commoditization than everyday communism. The majority of academic labor has been aggressively rationalized and made visible to employers, rendering academics (especially as instructors) more interchangeable, thereby giving schools more leverage. The story of how we got here is long and unpleasant, but given this reality, the one edge that employees have is an appeal to their success along the metrics they are forced to appease. Inhuman as it is, neoliberal control is still less brutal than old-fashioned coercion by threats of violence.

In this system, it is indeed a laudable act of self-assertion to insist on being paid fairly for one's labor. For people suffering from oppression due to a power imbalance (for example, women doing disproportionate labor in the household or community), a demand for payment as recognition of exploitation has been a powerful force for justice. From the perspective of a professor teaching eight classes a year for poverty wages, performing additional unpaid work for the edification of others is not an equilibrium strategy.

That is how I understood the contours of the "debate" over the payment of honoraria. The scare quotes indicate the absence of any real debate; indeed, I believe that legitimate debate on Twitter is impossible, that the affordances of the platform and the norms they have promoted render the idea of debate farcical.

*Part* of the pathology of Twitter communication stems inexorably from material inequalities. In earlier technosocial regimes, the connection between status/power and access to the means of communication enabled a kind of genteel exclusivity based on plausible ignorance: implicit in the fact of a debate was that all the participants had sufficient status to have access to the debate.

Twitter reveals a fundamental tension within the institution of academia. Narratively, academia is a safe harbor for the communal pursuit of knowledge and questioning the status quo. In practice, academia is incredibly hierarchical, unequal and small-c conservative. To some extent, this is unavoidable: the social function of academia relies on the premise of prestige and exclusivity, the belief that *our* practices of knowledge production are more valuable than the psuedo-science practiced by amateurs, that our expertise is real and valuable. The value arcane rituals and arbitrary "trials of strength" (GRE scores, comprehensive exams) cannot be dismissed out of hand, especially in the light of the growing demands for full epistemic equality by those with illegitimate claims.

How large can we make the mutual-support bubble until it bursts [call this Q*]? Those on the outside say "larger." Those on the inside prefer to say nothing, to affect the charming absentmindedness that sufficed to win these arguments by default when the physical architecture of the Ivory Tower was a dominant technology in rhetorical battle.

I don't know what the answer is; no one does. Underlying our post-Enlightenment, liberal democratic society is the idea that human reason and in particular *public* reason is capable of governing society. So in order to figure out how to address academic inequality (or indeed any societal issue), we need to either figure out how to use Twitter better or work on building some alternative. What we're doing now is not working.

“Deliberative democracy” is a major topic in political theory. My gloss is that compared to just voting, the act of deliberation encourages both the efficient use of information in decision-making and enhances the legitimacy of the eventual decision.

I came to the concept through James Fishkin, who argues that the following are necessary for “legitimate” deliberation:

Diversity: The extent to which the major position in the public are represented by participants in the discussion

Conscientiousness: The extent to which participants sincerely weigh the merits of the arguments

Equal consideration: The extent to which arguments offered by all participants are considered on the merits regardless of which participants offer them

I ran into issues trying to publish a paper about deliberation on Twitter, though; as one peer reviewer put it, why would we think Twitter is anywhere close to being conducive to deliberation?

Part of the issue is that the language we use for meta-discussion lacks the specificity required for the explosion of communicative modalities. In other words: philosophers positing ideal contexts for communication use words like “say” and “write”, and political activists criticizing others’ communication use words like “say” and “write.”

As I recently blogged, the language of the First Amendment (“speech,” “press,” “assemble”) was based on a technosocial context that is very far removed from Twitter or OnlyFans. The same problem obtains for our more informal norms and processes of communication, for things like deliberation.

So we can look at Fishkin’s list and correctly identify that Twitter is low in diversity, conscientiousness and equal consideration. But the problem is deeper; the words “argument” and “discussion” seem unmarked, timeless — but they in fact smuggle in assumptions about the embodiment, visibility and traceability of the participants.

Still, we can figure out how to use Twitter better [Q**], so that we might reach resolution to the question of academic standing and then honoraria. One strategy is to attempt to cut the technology down, to hamstring and squish it so that it can better approximate the theoretical ideals created in a previous technosocial context. I think this would be a mistake, a flimsy band-aid soon overwhelmed.

Better to adapt norms that make sense, beginning with the technology and with the social context in which it is embedded. Some of these norms have already developed. For example, it is considered gauche for an account with many followers to attack a random, no-name account with few followers—a quantified “punching down” that implicitly authorizes the bigger gang of followers to rain down abuse. Another clear norm violation is to “@” only the senior author of a co-authored paper under discussion, and especially to omit reference to nonwhite and female co-authors.

Humans are culturally attuned to picking up embodied norms — we take in far more information than we realize when we can see the body language of others. I suspect that norms of Twitter behavior will take longer to coalesce, and some may never reach any kind of equilibrium. There is a steep gradient among Twitter users in their ability to “read the room.”

So it seems worthwhile to talk about these norms more explicitly, somewhere that’s not Twitter. Not just norms in terms of “prohibited/allowed,” but norms about the connotations of some of the actions afforded by Twitter. For example, when two academics are going back and forth in a long comment thread and then one of them quote-tweets the other critically, this is an aggro move. It may or may not be justified—that depends on the circumstances, of course—but it’s useful for everyone to understand the social and emotional valence of such an action.

Taking a step back: there is not an order in which I can punch these damn keys that can convince you of this. The textual medium is insufficient. Take a second and be in your body.

Feel what it's like to grasp at some shared interest with an impromptu group of acquaintances at a wedding. To argue politics with a close friend at dinner. To discuss masking norms in a voluntary association--an AA or PTA meeting. To give a professional presentation to bosses or higher-ups.

Now feel what it's like to tweet: to self-promote, to respond to a stranger, to "quote-tweet" dunk on a famous but execrable account, to permute the main characters of the day with locally-relevant memes. And then to wait distractedly for the notifications.

Perhaps you don't tweet. In my PhD seminar this semester, we talk about social media a lot. All of my students use Twitter, but none of them *tweet*. I had prepared a lecture to highlight what I experience as the central affordance of Twitter (the damned Notifications bell), but none of them could relate.

You know damn well for whom that thing’s tolling

The biggest "media effect" of Twitter is not (contrary to the distribution of academic attention) how many random small accounts follow 0, 1 or 10 Russian bots. The biggest media effect of Twitter is how it warps the brains of the medium-to-large accounts which have usurped the roles of both Walter Cronkite and local party cadres in translating the events of the world into the language of the average citizen.

Perhaps I’m projecting, that I am uniquely susceptible to this kind of feedback and the rest of y’all are stoically tweeting your truths, unbothered by the fickle whims of the crowd. Having met some of you in person, I suspect this is not the case. But the severely diminished mutual observability of this aspect of Twitter makes it impossible to be sure: none of us can know how much time the rest of us spend obsessing over feedback.

The best hope we have, in my opinion, is to start talking about all this stuff off of Twitter.

Like, it’s possible that the status quo is optimal or at least healthy. That letting the Twitter System greedily devour the knowledge processes of our previous technosocial regime, like a cancerous tumor optimized only for growth, has led us to a normatively desirable discursive place.

We should certainly give some credence to the many Twitter users who refer to it as the “heaven site,” whose praise for its effect on our democracy and culture has only grown more effusive in recent years.

But as delightful as Twitter is today, perhaps we can, collectively, decide how to make it even better?

Or else (my preferred solution) we can take stock of the social arrangements made possible by the outrageous progress in communication technology over the past few decades. We could then decide whether the software designed by Jack Dorsey fifteen years ago to send group texts and optimized for growth ever since can in fact be used for our purposes, for promoting informational flows that are necessary for a healthy democracy [Q***].

Y’all are smart, of course. You know all about collective action problems and would never play a non-equilibrium strategy, never unilaterally incur a cost when you know everyone else will shirk or free-ride.

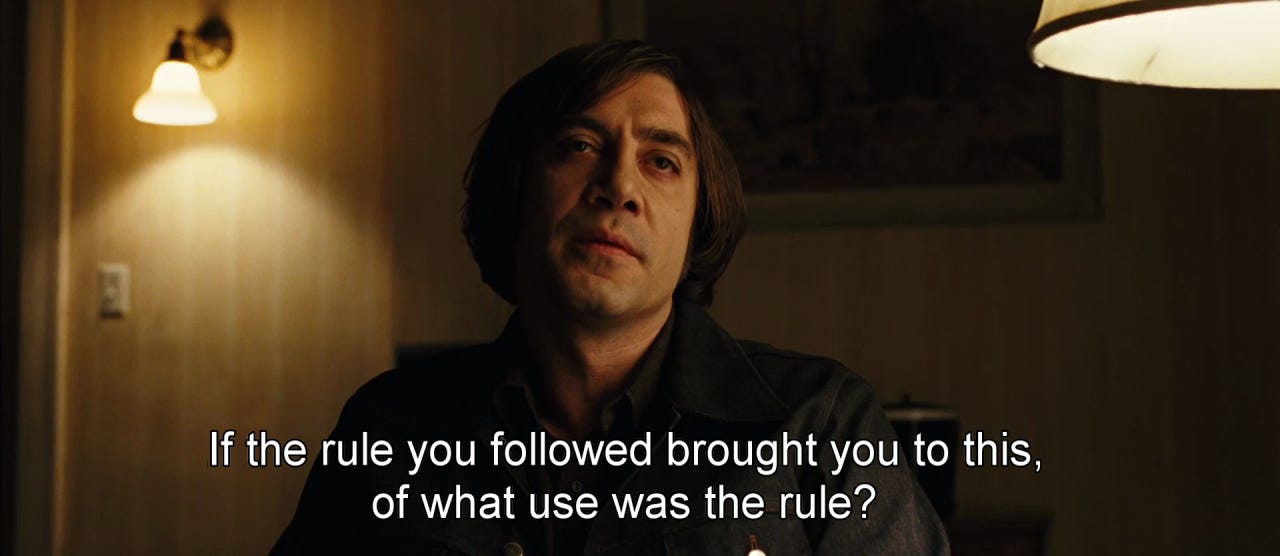

I miss this guy he was cool

This is a meta-meta-meta-question. (Sorry, true).

The question is whether to pay academics an honorarium. [Q]

The meta-question is how to evaluate the relative standing of academics at different levels of the status hierarchy. [Q*]

The meta-meta-question is what norms of Twitter use can produce the best answers to question [Q*] and thus question [Q]. [Q**]

And the meta-meta-meta-question is whether the technological affordances of Twitter are in fact compatible with the establishment of norms that enable us to reach this possibility frontier, or whether we would be better off with a different medium. [Q***]

It's harder to point to an absence than a presence. The pandemic inverted my social life. The digitally-mediated became normal, so it was easier to notice the novel elements of meatspace interaction. Most important for my argument is *meta-learning*: we can observe how others learn from novel stimuli based on their physical responses. One concrete step we can all take towards promoting healthier discourse is being more transparent about how we use Twitter.

The next step is for everyone to elevate the status of my subfield of research. (Sorry, also true.) Diagnosing the problem—making it legible to the human actors comprising the Twitter System system who feel their dignity and autonomy eroded but lack the categories to understand why—is necessary for developing new norms and regulations. Social media has shocked every social, economic and political system; until we understand how it continues to shock our knowledge system, we are unable to formulate coherent responses anywhere.