Like many other academic institutions, my university is currently considering whether to cease posting on X. Last week, I participated in a panel discussion on “the evolving dynamics of tech companies’ roles in shaping online communication” and whether X was still a channel worth using. As an expert in media economics and the effects of shifting platform dynamics, my position is that the university should quit the platform — and furthermore, that they should think seriously about their goals and strategies before joining an X replacement like Bluesky.

I expand on this argument in a recent article in the Chronicle of Higher Education—the full article has some political musings, including about Elon Musk. Which is, apparently, the main thing people who have left X want to talk about, if the BlueSky subreddit is any indication. But I have long argued that a politics based on selecting a preferred billionaire’s persona is bankrupt; I’m far more interested in the open-ended prospective question, of how academics and academic institutions should use the internet.

The decision is analogous to recent debates about whether universities should issue “statements” about current events. Harvard and Penn, for example and presumably for similar reasons, have walked back their policy:

“Going forward, the University of Pennsylvania and its leaders will refrain from institutional statements made in response to local and world events.”

They’ve realized that the absence of statements is now interpreted as a statement itself. The gift of ubiquitous communication is revealed to be a curse.

In their 2024 book The Ordinal Society, Marion Fourcade and Kieran Healy analyze the dynamics of social media using a classic example of sociological theory. They apply Marcel Mauss’s idea of “the gift” as a powerful and potentially destabilizing social technology. Unlike a market exchange in which both sides of a transaction are, in principle, even, gifts leave the receiver in debt to the giver. The free communication offered by social media puts us in a tenuous social position. If we were customers, paying for a service, we could more easily think about costs and benefits, and have recourse to legal protections. But as giftees, we have no bargaining power. Who wants to look a gift horse in the mouth? Our only choice is whether to keep on receiving or to say “no thanks.”

Moreover, the quantified feedback provided by social-media platforms is both seductive and addictive. So many corporate, governmental, and nonprofit organizations have been tricked by ever-increasing view counts into thinking that they’re communicating better — while, on an ecosystem level, it’s clear that our status and capacity has been diminishing every year. Competing for marginal “views” with charlatans like Andrew Tate is a net negative; it damages our reputation for excellence. By commodifying our output, by accepting the platform protocols which treat our scientific or institutional communication exactly the same as trolls and hucksters, we are reducing ourselves to their level.

This is, I acknowledge, an elitist position — but some degree of elitism is inevitable when you’re in the business of expertise. Academe’s position in society is premised on the value of rigorously curated knowledge. As we push the limits of natural science, as we make sense of the social world, and as we impart this knowledge to younger generations, the only justification for asking our fellow citizens to let us dress up in fancy robes and call each other “Doctor” is that this is part of a higher level of epistemic inquiry.

If we want to be in the business of public-facing communication, we need to invest in high-quality digital real estate. Concretely, we need to develop “places” (apps, websites, even physical public spaces) that are persistent attractors for people who are actually interested in the kind of communication that only academics can produce. This means doubling down on our core value proposition. Chasing short-term audience maximization diminishes our unique contributions.

Institutions of higher learning who are rethinking their communications strategy in the wake of Trump’s victory should consider investing in high-status, high-quality public lectures highlighting the expertise that we have worked so hard to come by. Not every institution needs to spend money on internet-wide communications. The Gift of Twitter lulled us into thinking this was both essential and low-cost. But a perfunctory online presence can do more reputational harm than good. For institutions with a budget, it makes more sense to invest in digital real estate they own, and to communicate in the modality which is most relevant to the majority of the public: video.

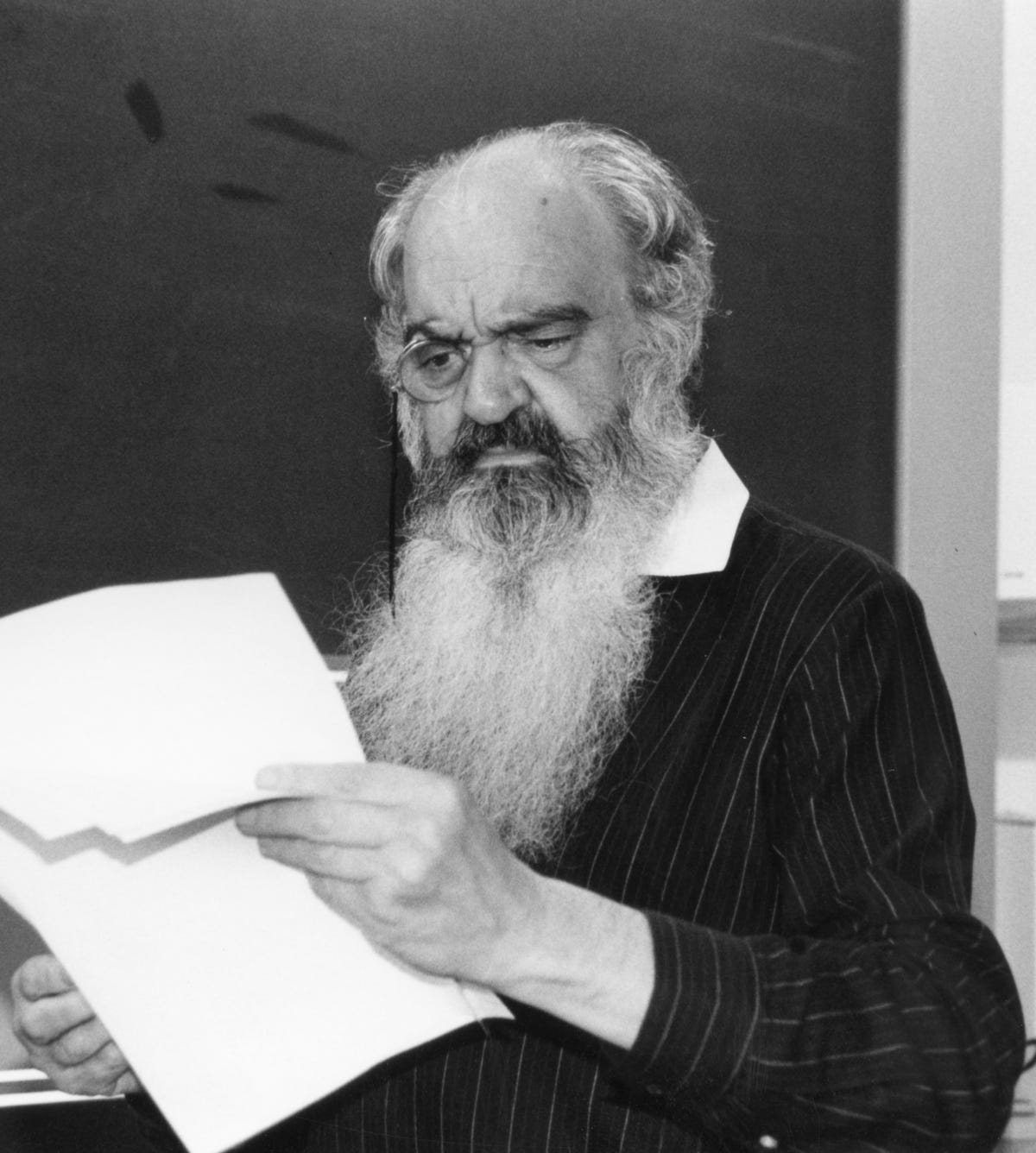

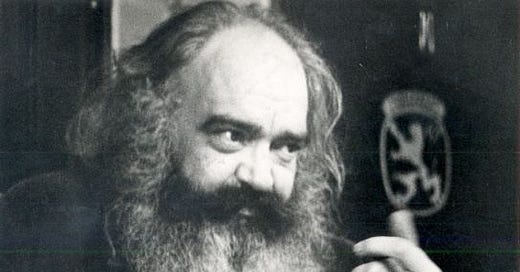

In the rest of the article, I make the case for investing in high-quality video-based communication; read the whole thing if you’re interested. But you’re probably better off listening to Stafford Beer’s 1973 Massey Lecture, an amazing example of public scholarship and my inspiration for this recommendation. There is an appetite for high-quality, rigorous audiovisual academic output; we need to meet it.

Enjoyed this article, Kevin, thank you. Curious to hear your thoughts on research-oriented sites like Academia.edu ?

Hear hear!