Discover more from Never Met a Science

If you and your community have not invested serious energy taking advantage of the internet revolution -- if you do not have a concrete set of norms, practices and institutions designed to allow you to use the internet without the internet using you -- you are destined to lose. In fact, you’re not even trying to win.

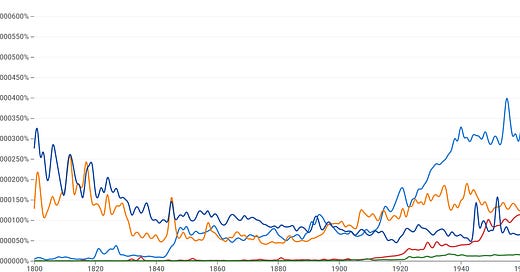

The platform web has cannibalized liberal/literate culture overnight. Twitter is a “deliberation-themed video game” that has deformed real, vibrant humans into bitter cyborgs competing to dehumanize and degrade. Twitter culture is Cruelty Culture. This epicenter of intellectual/cultural/political activity is proudly incompatible with liberalism.

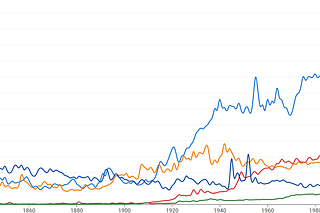

The “thick liberalism” of the past centuries has been rendered obsolete by new media technologies. The groups who can harness the internet for their own ends will decide what comes next.

But I am (still) a liberal (for now) in the “thin” sense, the sense in which avoiding human cruelty and humiliation should be a central political goal. Twitter Cruelty Culture is what illiberal intellectual ironism looks like. And it is an abomination.

I have recently been Rorty-pilled. I wrote about him earlier this year, but to recap: Richard Rorty was a controversial and idiosyncratic American philosopher. He self-identified as a (American) Pragmatist, in the lineage of Peirce, James and (especially) Dewey, so his general orientation did not agree with either the dominant American analytic tradition or the more critical “Continental” tradition.

Rorty is a self-avowed liberal, with two related conceptions of liberal: someone who believes cruelty is the worst thing that can happen to a human being (what I’m calling “thin”), and someone who believes that values of political liberalism (freedom of speech, representative democracy, toleration) are the best way to achieve a reduction in human cruelty and suffering (“thick”).

The problem for Rorty, as for so many of the thinkers from the Gutenberg Parenthesis, is that they are unavoidably embedded in the culture made possible by the technology of writing. That is: he needs more McLuhan. Freedom of speech, representative democracy toleration: these are all products of a literate culture, designed/discovered to take advantage of writing's strengths and ameliorate its weaknesses.

If Rorty were alive and reading my blog, I like to think that he'd agree with me that his second conception of liberalism is less tenable than it once was. At least, I'm confident that he would be open to argument on this point: contingency is his whole bag.

Contingency means that there are no universal truths, only local ones. And “truths” (in the classic Pragmatist definition) are beliefs that are useful for humans in achieving their desired ends. As a philosophy of science, this aligns beautifully with my developing framework for thinking about meta-science: eternal validity is impossible, so we need to decide how to allocate our scarce social scientific resources; this decision requires some agreement about what our desired ends are; meta-science produces “knowledge” that is useful for doing normal science to better achieve our desired ends.

But back to liberalism. Maybe you're surprised to hear that liberalism is even on the table; isn’t this obviously the bedrock of our shared political culture? Well, yes, it *was*, even relatively recently. But the vanguard in every ideological direction just does not give a shit about liberalism, and these bedrock liberal values are looking far more unstable than they did even ten years ago. Liam Bright recently laid out a brilliant materialist/historicist argument for why he is not a liberal; leftist activists and MAGA Republicans alike are openly derisive of the “libs.” The latter have been successful—almost literally—in torching our liberal political institutions. On the intellectual right, neo-reactionary and Catholic integralist ideas are getting serious traction.

Regardless: I am a still a liberal, for now, because of Rorty’s first conception of liberalism as solidarity with our fellow humans, what he calls “liberal hope.” I don't buy “thicker” conceptions of liberalism (because they are technologically determined and out of date) and I don't think that this thin liberalism has a wide range of practical applications. But I do think it is still necessary, for now, because of just how bleak things are without it. I believe that the ongoing effects of the Internet Revolution will make everything so different that the premises and categories we have inherited, what we use to define our liberal world, will cease to make sense.

Long run, I’m optimistic about this. Countries, religions, corporations, events --- even the historical concept of time --- these concepts all disguise the human subjects underneath. Our agreement that the strings of characters “1650” and “1995” are commensurate is contingent on the technology of literacy. An alternative chronology, defined by human lives, would see “1650” as commensurate with “January 1995.”

The point is that our mental maps of the world are entirely contingent: there is no fixed point to which we can retreat. I'll explore this point through my favorite of Rorty’s books.

Rorty's Contingency, Irony and Solidarity feels to me like the high water mark of liberal philosophy. Liberal politics in the West, Rorty argues, crested with WWII. Our present malaise and turn towards illiberal politics reflects the confirmed pessimism that we have no concrete plans for reaching the theoretically possible worlds full of human dignity, freedom and peace.

Rorty's first move in CIS is to clarify the foundational liberal distinction between public and private philosophy. Public philosophy is necessary for determining how people can live together, and it applies to everyone. Aristotle, Burke, Hegel, and Habermas are public philosophers. [Tossing around these names is relevant.]

Private philosophy is a genre of literature that appeals to the small percentage of humans with an implacable drive for self-creation, who refuse the terms they are given for understanding the world, who aspire to be judged according to criteria which they establish. Plato, Nietzche, Heidegger, Sartre and Derrida are private philosophers; in Rorty's estimation, they are best understood as analogous to authors like Proust, Nabokov and Orwell.

These private philosophers are what Rorty calls ironists, people who take nothing for granted: not the society in which they live, not some transcendent bedrock like Truth or God, not even the language with which they are taught to conceive of and discuss the world they inherit. His use of the term is not obvious for people who get hung up on debates about the Alanis Morrissette song, but it resonated deeply with my experience as an “ironic” adolescent intellectual in the 2000s.

This definition of the ironist hit too close to home: “the person who has doubts about his own final vocabulary, his own moral identity, and perhaps his own sanity --- desperately needs to talk to other people, needs this with the same urgency as people need to make love. He needs to do so because only conversation enables him to handle these doubts and these needs because, for one reason or another, socialization did not entirely take.” I’ve you ever met me at like an academic conference, this passage might help explain why I’m like that.

Rorty is thus a liberal ironist. The term is a paradox, a kind of zen koan or existentialist puzzle. There can be no principled way for the ironist to justify liberalism and yet Rorty believed that he must act as though he believed. (There are parallels to Kierkegaard without the terrifying leap/retreat to Christianity.)

Nietzche is the prime example of an illiberal ironist; Rorty describes him as “at best useless and at worst dangerous” as a public philosopher. And yet public Nietzchianism is on the rise, in a post-liberal world rife with capacity/efficacy/skill inequality. The will to power is an appealing moral framework for those with more power and fewer checks on how they can use it.

Rorty's exegesis of Orwell’s 1984 shows that ironism can be used to any imaginable ends.

Orwell “broke the power of what Nabokov called ‘Bolshevik propaganda’ over the minds of liberal intellectuals in England and America,” twenty years ahead of the French. He “sensitized his readers to to a set of excuses for cruelty which had been put into circulation by a particular group -- the use of the rhetoric of ‘human equality’ by intellectuals who had allied themselves with a spectacularly successful criminal gang.”

Animal Farm was a targeted intervention into a specific intellectual environment. Postwar political discourse had become unproductive because of the insufficiency of the categories being used to describe the political world. Orwell illustrated the accumulating inconsistencies in the words “socialism” and “fascism,” the inability of this conceptual division to enable useful synthesis. The childish directness of the allegory in Animal Farm is necessary to redescribe the political world in new terms, ones not weighted down by decades of accumulated associations and implications. This “rediscription” is the primary move of the Rortian intellectual, the analogue of the revolutionary (rather than normal) scientist and the utopian (rather than pragmatic) politician.

The first two-thirds of 1984 follow the style of Animal Farm. But reading the book at fifteen, I failed to understand that the last third of the book is not about Winston but about his torturer, O’Brien. (Many of Orwell’s contemporary critics also either didn’t understand or hated the ending, but having re-read it, Rorty’s account seems more plausible.) O’Brien is not a basic torturer, someone whose methods apply equally to all the animals which feel pain. He is an ironist intellectual doing what intellectuals are allowed to do in this society.

O’Brien is a terrifying example of what radical irony can entail. Technology has made human equality technically possible, but the ironist understands that it is equally likely to make “endless slavery possible....[that] there is nothing in the nature of truth, or man, or history to block this scenario.”

Humans share with animals the capacity to feel pain, but we also have a higher faculty. We experience a “special kind of pain: we can all be humiliated by the forcible tearing down of the particular structures of language and belief in which we were socialized (or which we pride ourselves on having formed for ourselves)…we can be used, and animals cannot, to gratify O’Brien’s wish to ‘tear human minds to pieces and put them together again in new shapes of your own choosing.’”

Rorty cites Elaine Scarry to say that the point of sadism is humiliation; screams of agony are not cruel in the specifically human way unless they are used to prevent the victim from ever recovering. The goal is to “get her to do or say things -- or if possible, believe and desire things, think thoughts -- which later she will be unable to cope with having done or thought...making it impossible for her to use language to describe what she has been.”

O'Brien says that “the object of torture is torture.” Per Rorty, “for a gifted and sensitive intellectual living in a posttotalitarian culture, this sentence is the analogue of ‘Art for art’s sake’ or ‘Truth for its own sake,’ for torture is now the only art form and the only intellectual discipline available to such a person."

O'Brien doesn't need to do any of this torturing; in the book, Winston achieves nothing and could have simply been shot on page 5. We can imagine that his job within the Party involves a community of totalitarian ironists, that they have symposiums and academic journals where they discuss the methods and celebrate the successes of torture by humiliation. This is the space he is allocated for creativity, and he uses it -- just as any intellectual ironist would:

“Orwell was the first to ask how intellectuals in [totalitarian] states might conceive of themselves, once it had become clear that liberal ideals had no relation to a possible human future. O’Brien is his answer to that question…O’Brien is employed in the only way in which the end of liberal hope permits irony to be employed.”

As an avid Twitter user, I found this description nauseating, disgusting. Twitter is The Coliseum of illiberal ironism. Absent liberal hope, we see a spectrum of contingent intellectual communities emerge. There are poets, aristocrats, inquisitors and monks, in addition to a fecundity of intellectual forms with no historical analogue. But the primary form --- because of the distinctly Darwinian streak in American society, because of the architecture or userbase of Twitter, because of declining material conditions --- is intellectual cruelty.

The truest joy the illiberal ironist embedded in Cruelty Culture ever feels is the realization that they have both the social license to be cruel and a sophisticated enough understanding to inflict maximum humiliation.

We exist in communities which exult in cruelty. We compete to be the best at it.

We aspire to be O’Brien.

Rorty has no solutions, cannot even appeal to some unshakeable bedrock of “human nature.” He offers simply his contingent belief in thin liberalism, the desire to avoid human cruelty.

Thick liberalism—again, freedom of speech, representative democracy, toleration—is crumbling. Made possible by the technology of writing, liberalism as we know it is not compatible with the internet and social media; see the recent excellent book on the Paradox of Democracy by Sean Illing and Zac Gershberg for the historical case.

This long-term perspective explains the bitter ineffectualness of contemporary wordcels, a neologism that seems more and more prescient.

We are experiencing a psychic crisis. Downward mobility, as Millennials know all too well, is the first step towards the war of all against all. Hypercompetitiveness creates Stockholm syndrome, abandoning the principles we had used to define ourselves, and eventually burnout.

We are witnessing the downward mobility of the entire medium, a once too-proud literate/liberal culture shredded by a technological -> economic -> cultural revolution in media.

Twitter cruelty is the last stand. While the median American Twitter user is still either an awkward 17-year old running a BTS stan account or a dad in his 30s who is way too into the NBA, there are a reserve army of the unverified who define mainstream Twitter culture. Twitter remains a niche platform, so this army is not representative of the population. As the deformed bastard child of literate culture, Twitter is composed of wordcels attracted by delusions of agency and control. Over-educated under-successful former “gifted children” are loudly depressed, anxious and alienated, determined to inflict themselves on the successful and well-adjusted.

(McLuhan: “Our Age of Anxiety is in great part the result of trying to do today’s job with yesterday’s tools—with yesterday’s concepts.”)

The consensus culture developed and enforced by Twitter wordcels is that it is acceptable and even morally supererogatory to degrade and humiliate anyone you disagree with or anyone with a moderate amount of followers, fame, wealth or power.

As this culture developed over the past decade, wordcels sometimes used tenuous consequentialist arguments to justify this behavior. According to [insert political framework], the target is Bad, so humiliating them and causing them pain is Good.

This justification is no longer necessary. Cruelty Culture is hegemonic, reinforced by the platform architecture and the longstanding human processes of mimesis and scapegoating.

Like Orwell on socialism/fascism, I’m specifically avoiding talking about “cancel culture” because there’s too much baggage, the phrase is simply not useful: by focusing on the moral status and the consequences suffered by the target, debates about “cancel culture” reify the premises of illiberal Twitter cruelty.

“Cruelty Culture” calls attention to the perpetrators of cruelty, how playing this miserable game warps our moral and political senses.

The people tweeting “#JohnDoeIsOverParty” with a gif of eating popcorn, revelling in the details of the worst humiliation in someone’s life.

The quote-tweet pundits far more interested in “bad takes” than “good takes” because the former give them license delivery the cruelty that their followers then reward with Likes.

The abject bullies who have convinced us that mocking people’s appearance is a reasonable way for adults to behave.

The US President who revealed precisely what Cruelty Culture looks like, the kind of people and politics it empowers.

As I wrote in “Facebook is Other People,” we are reaping what we’ve sown. The democratization of communication technology has forced those at the center of liberal/literate institutional power to reckon with millions of people screaming about how miserable they are, how much they hate us. McLuhan knew back in 1967 that “in an electric media environment, minority groups can no longer by contained—ignored.” Bitter, downwardly-mobile wordcels are one such group who has figured out how not to be ignored.

The center has responded by fighting back against the most obviously harmful instances of this backlash: misinformation, hate speech, threats, doxxing. But they’re flailing, they have nothing to offer, no path forward.

The “live actors” who will determine the future are today organizing in private, accumulating talent, capital and experience, figuring out how to use the awesome power of the internet in new ways.

The “dead actors” are trapped in Skinner boxes, trying to do today’s job with yesterday’s tools, morally and politically enfeebled by the awesome power of the internet as designed by tech billionaires, every day competing to win a perverse game.

Defending thin liberalism—ceasing to valorize cruelty—won’t solve the problem of what comes next. But it will help us preserve some dignity and humanity in this inhuman time.