What Are Survey Experiments For?

The titular question emerged as I was working with Alessandro Vecchiato on our visual conjoint experiment, just published at the Journal of Experimental Political Science:

Introducing the Visual Conjoint, with an Application to Candidate Evaluation on Social Media

I’ll discuss the specific lessons of the paper at the bottom of this post, including some novel problems of temporality and methodology. We think this is a much better way to be running (some!) candidate choice conjoint experiments, and that it opens up an exciting array of options that the traditional “box” conjoint can’t handle.

But first, the big picture: what is a survey experiment? What are they for?

Last spring, Yph Lelkes hosted a workshop at the Princeton Center for the Study of Democratic Politics that started me thinking along these lines. Survey experiments are a popular and therefore contentious method in contemporary political science research. There are competing camps arguing for (or against) survey experiments based on divergent epistemic commitments. But rather than wading headlong into the debate, I’m begin with some amateur history of social science.

The confusion over what survey experiments are for is because survey experiments represent the current state of the dialectical process of methodological progress of two distinct intellectual traditions: political science and public opinion research.1

In each case, the dialectic is between those two poles of Western thought: Plato and Aristotle, rationalism and empiricism, deduction and induction, theory and data. The crux of my argument is that different intellectual traditions have come to survey experiments for different reasons, and that this produces conflicts about how to evaluate and improve them.

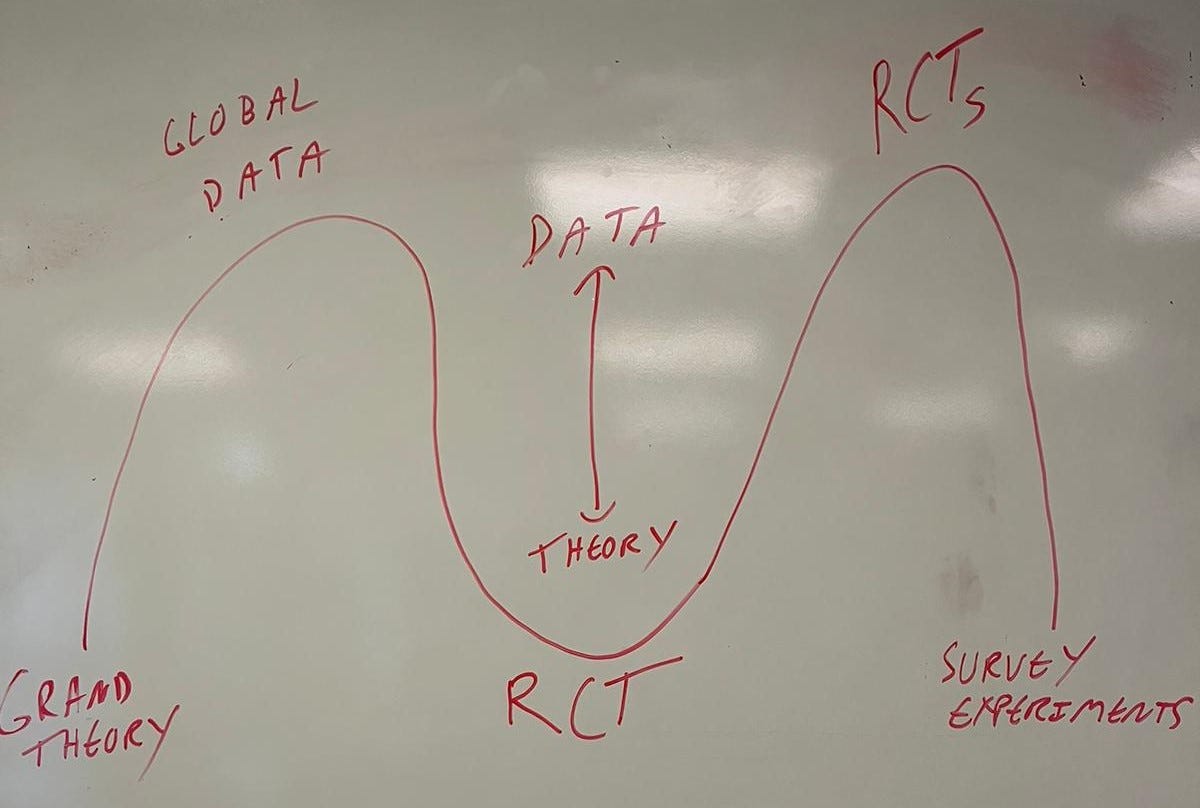

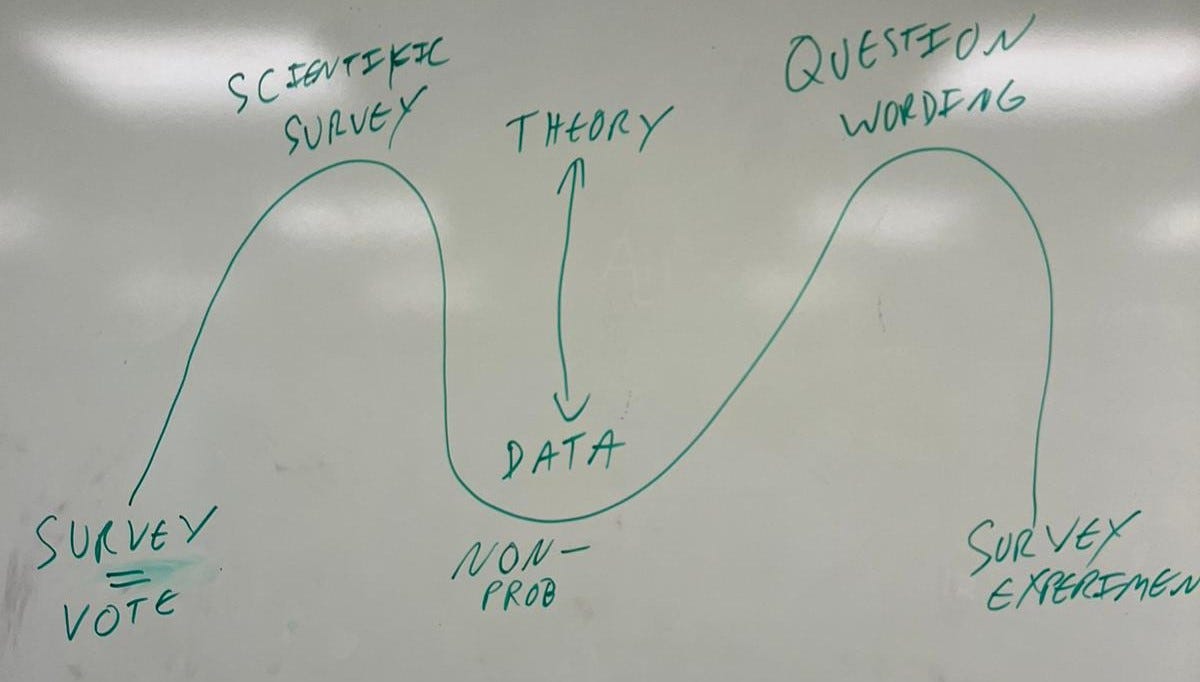

To re-emphasize the fact that this is amateur historical work, I’ll represent these historical trajectories with glare-ridden photos of a whiteboard. There are temporal problems with this analysis, and I’m not claiming that these trajectories capture all or even the central tendency of work within each discipline — but I think this is good enough to start with, and I invite suggested modifications.

First, let’s look at Political Science, the history I’m most confident in.

Pre-WWII, Political Science was hampered by a lack of data and so primarily involved grand theorization about political processes. The development of national and especially international time series datasets allowed for quantitative over-time and cross-country analysis, oftentimes to “test” those big theories — questions like whether democracy causes peace or how different electoral institutions promote government stability.

The application of Rational Choice Theory (RCT) to political processes like war, campaign strategy and voter turnout swung us back to the opposite pole of pure theory, this time based in methodological individualism and borrowing from Econ the rationality assumptions that make these models analytically tractable. Empirical data was of secondary importance or even irrelevant.

The next move was back to empiricism, from RCT to RCTs (Randomized Controlled Trials, or “field experiments”). This empiricism was causal empiricism — no cross-country econometric wizardry, just the steady accumulation of credible empirical cause-and-effect relationships towards an end of inducting theoretical results. The lexicographic preference for causal inference necessarily puts theory in second place. The vibe is that the world has only produced so many natural experiments or allowed us to conduct RCTs — let’s start there and see what happens.

And the lexicographic preference for credible causal inferences has persisted in the move back towards theory, in the form of survey experiments. The design space for survey experiments is much larger than for field experiments or observational causal inference — you can put whatever you want onto a website. So, the selection of which survey experiment to run has to be guided by theory. The “methodology” of survey experiments is therefore a satisficing exercise — we want to make sure we’re not doing anything wrong, anything that would hinder our inferences, but we are not really interested in the data per se.

Contrast this with the history of Public Opinion research.

We begin in the simplistic days of pre-scientific polling, where bigger polls were better but otherwise the results were seen to map directly onto “public opinion.” The always-hilarious failure of the 1936 Literary Digest poll, which missed the national vote by 39 percentage points, marked a unusually clear break with status quo methodology and made clear the need for a more theory-driven approach to measuring public opinion.

So Public Opinion came to worship the god of randomization several decades before RCTs took off in Political Science—with the invention of scientific surveys using probability-based random samples of the population. The size of the survey doesn’t matter beyond a certain (fairly low) level; randomization allows us to make the desired inference.

This tradition had a good run, but changing technology and social norms made techniques like random-digit dialing less effective. The response was the development of data-driven statistical techniques like MRP to allow for the credible use of non-probability surveys. By borrowing information from different data sources and using cross-validation, these non-probability samples aimed to infer public opinion absent access to a representative sample.

A more theory-driven question became especially salient as the time series of some public opinion surveys began to span decades. We love the technique of asking the exact same question over time in order to track how public opinion changes — but how do we handle the fact that the meaning of language is changing? We needed to think about what these questions mean, and a move towards studying question wording emerged.

So survey experiments represent the empirical response to theoretical questions about question wording. Rather than just thinking about what these different questions mean, we can experiment with them and see what differences there are.

The key difference, between the Public Opinion and Political Science uses of survey experiments, is that the former actually does care about the specific numbers — not just the implications for a theory, but what those numbers tell us about what our fellow citizens think.

Spelling out these distinct histories of survey experiments makes it clear that survey experiments are for different things. As these intellectual traditions become more intertwined — and especially as metascientific debates happen increasingly online, where the implicit disciplinary boundaries imposed by the physical realities of departmental buildings, conferences, and printed journals no longer obtain — there is often confusion and frustration.

Interdisciplinarity is good, but it requires both mutual clarity and mutual respect. There is thus a problem with “methodology” that does not have explicit meta-scientific scope conditions — a universalist methodology-by-decree is anti-scientific.

Alessandro and I are quite explicit about this in our paper:

Our results do not demonstrate that a visual conjoint created in the style of a Twitter profile is “better” than a box conjoint…No research design can generate a universally valid estimate of voter preferences; research on this topic, like all empirical research, can only be valid within specified scope conditions.

The problem is when authors (or reviewers!) take a “cookbook” approach to research design, desiring or insisting on following the correct procedure according to the high priests of methodology.

I was amused by a slide from an excellent presentation I saw recently which makes this sociological process all too clear. To justify the statistical approach, the author cited a presentation by Econ “Nobelist” Guido Imbens2: “Remember DDDiD: Don’t Do Difference-in-Differences.”

Clean, simple, universal. Maybe it’s even true — we should never use this particular statistical method. But this produces another problem: how do we treat the knowledge generated by published papers using this method?

Alessandro and I encountered this problem during the peer review process. We pre-registered our study design, including a power analysis based on effect sizes from published conjoint experiments to determine the sample size.

When we submitted the paper for review, however, the reviewers pointed us to a paper by Liu and Shiraito about the use of an adaptive shrinkage estimator to calculate the standard errors for conjoint experiments. The adaptive shrinkage paper had been published after we pre-registered our experiment, but the reviewers still wanted us to implement the estimator — even though it meant that our study was underpowered.

Thankfully, the main results held up with the new estimator. But is this “fair”? Should papers be held to a methodological standard that didn’t exist when they were pre-registered? Or, alternatively, is it scientific to publish papers that we no longer think use appropriate methods?

And does the exact timing matter? Apparently, their paper was published online about 40 days before our pre-registration was uploaded (even though we didn’t know about it). What if it were 4 days, or 400?

And there is another thorny question with respect to how we compare our results with published results from the past.

Classic conjoint experiments had found significant effects of, for example, candidate religion. Our non-adjusted experiment replicates these findings. However, our adjusted results find no effect for candidate religion.

How should we summarize this?

Can we honestly say “classic studies find support for the effect of candidate religion” without going back and re-running the analysis with the adaptive shrinkage estimator? Is it better to amend the scientific record — or is this methodological overreach?

There are plausible arguments on both side of these questions. What do you think?

This should probably include also Psychology and media effects research from Comm. But it’s already complicated enough and I don’t know enough about these — I read Wikipedia about Wundt and cognitivism but the history I came up with wasn’t even baked enough for a blog.

No shade on Imbens, but it’s always worth repeating that the “Econ Nobel” is fake.

Ultimately, it's better to publish studies with code and data in a reproducible format, so that studies can be updated/re-analyzed as the community finds it worthwhile to do so. Viewing papers as static documents that represent "truthiness" for a particular claim even as our priors/methods/the reasons a data set is interesting change is a massive problem in the scientific literature.

Your discussion of the "cookbook" mentality of reviewers brought this to mind conversations about what science would look like if we acknowledge the affordances of new media. What if studies did not result in "papers" which must be printed to be disseminated and are thus fixed and immutable once published, but took the form of a collaborative repository roughly similar to git? We can imagine forking the repository to reanalyze data in light of methodological advances and integrating the new results to release a new version of the study. This leads to obvious questions about academic credit and incentives that don't have straightforward answers.