Discover more from Never Met a Science

There are many processes now subsumed under the term “Artificial Intelligence.” The reason we’re talking about it now, though, is that the websites are doing things we never thought websites could do. The pixels of our devices light up like never before. Techno-optimists believe that we’re nowhere close to the limit, that websites will continue to dazzle us — and I hope that this reframing helps put AI in perspective.

Because the first step in the “Artificial Intelligence” process is most important: the creation of an artificial world in which this non-human intelligence can operate.

Artificial Intelligence is intelligence within an artificial space. When humans act within an artificial space, their intelligence is artificial—their operations are indistinguishable from the actions of other actors within the artificial space.

Note that these aren’t arguments; they’re definitions. This territory is changing so rapidly under our feet that we need to be constantly updating our maps. Most conversations about AI are simply confused; my aim in this essay is to propose a new formulation which affords some clarity.

One more definition: Cybernetics is the study of the interface between the human and the artificial—how we can interface with the artificial in order to harness it while retaining our agency. I’ve written before that cybernetics provides key insights from the first integration of computers into both social science and society, but reading these old texts demonstrates how rapidly the artificial has grown from the 1950s/60s to today. The earliest cybernetics centered human biology, our muscles and sensory apparatus, drawing from phenomenology; today, the computer/smartphone/digital interface is the focal point, our gateway to the artificial. Humans and the non-human world revolve around the screen; todays’ cybernetics requires a machine phenomenology.

Concerns about “alignment,” the mismatch between human values and their instantiation in the machine, are often addressed towards making the artificial world match the human world (real or ideal). I argue that this approach cannot succeed, due to human constraints in speed and information density. We simply cannot verify that these sprawling artificial spaces are aligned with our values, either inductively or deductively, for reasons related to the philosophy of science topics I usually blog about.

The most important first step towards a society with a healthy relationship to AI is to slow and ultimately limit the growth of the artificial. This will take active effort; the business model of “tech companies” involves enticing us to throw everything we can into their artificial little worlds. The entirety of the existing social world we’ve inherited and had been maintaining or expanding is like a healthy, vibrant ecosystem — and tech wants to clearcut it. Individual people can get ahead by accepting the bargain, making this a tragedy of the commons.

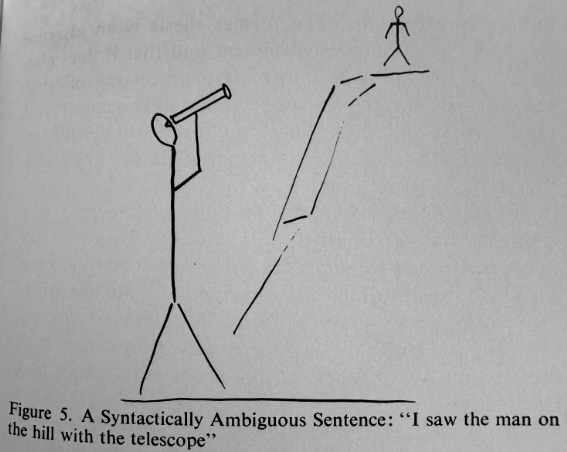

Metaphorical work is an essential if understudied methodological input to the process of social science. This is my primary intervention: AI is a whirlpool sucking the human lifeworld into the artificial. Social media is the most complete example: a low-dimensional artificial replacement for human sociality and communication, with built-in feedback both public (likes) and private (clicks). The objection function for which recommendation algorithms optimize is time on the platform, as Nick Seaver documents. These explicit goal of these platforms is literally to capture us.

The more we are drawn into these artificial worlds, the less capable we are as humans. All of our existing liberal/modern institutions are premised on other lower-level social/biological processes, but especially the individual as a coherent, continuous, contiguous self. Artificial whirlpools capture some aspect of previously indivisible individuals and pulls us apart — sapping energy from generative, creative, and regulative processes like social reproduction and democracy.

As we use our intelligence to navigate artificial spaces which record our actions, the more training data we provide to “artificial intelligence” which can then act at superhuman speed and scale in these spaces. The “artificial” is a replacement of the real world with an ontologically simple low-dimensional model, as formulated by Herbert Simon, James C. Scott, and other thinkers influenced by cybernetics.

Humans have always created artificial worlds, from cave paintings to mathematical systems, within which to perform symbolic operations and produce novel insights. The effective application of this process has granted humans mastery over the natural

world and, often, over other humans. Our artificial worlds representing of molecules, proteins, bacteria, stars – these are domains where AI can and should be applied, where it will help us more efficiently exploit the spaces we have created.

Every new result proclaiming how AI bests humans at some task is a confession that humans have already been reduced to some artificial aspect of ourselves.

But AI is being used to exploit artificial spaces which we have created to stand in for and manage humans. Every new result proclaiming how AI bests humans at some task is a confession that humans have already been reduced to some artificial aspect of ourselves.

Historically, the temporality of this process had been limited to that of the humans creating, manipulating, and translating these artificial worlds. The modern bureaucratic state constructs artificial representations of its citizens in order to govern them. This is technocratic; democratic oversight is supposed to skip straight to the top. There are human intelligences coming up with the categories and deciding how to interact with them. Democratic politics is the means by which we change these categories and relations.

As more inputs to the artificial worlds became machine-readable, the expansion of the AI process began to transcend human temporalities, constrained as they are by biological realities of the life cycle. Postmodern bureaucracy does not rely on human intelligence to define the ontology of the artificial space; machines induct the relevant categories from ever-growing streams of data. Electoral democracy is thus unable to serve its regulatory function – postmodern, inductive bureaucracy is an Unaccountability Machine.

The most recent jump, the impetus for widespread discussion of AI, came not from LLMs themselves but from the introduction of the chat interface. LLMs were made possible by huge data inputs in the artificial world of text, and by advances in the statistical technology of machine learning. But it was the human-world hookup that proved key for widespread adoption – and thus a slope change in the rate of the expansion of the artificial.

For the domains of human life which have already been made artificial, there is little hope of fundamentally stopping AI. There is no reason to expect humans to best machines at artificial benchmarks. Any quantified task is already artificial; the more humans perform the task (and, crucially, are measured and evaluated in performing the task), the better machines can optimize for it it. The process is brutally fast and efficient, a simple question of data flows, the cost of compute and perhaps (under)paying for some human tutors for RLHF.

Empirical and technical approaches to AI are fighting on an important but ultimately rearguard front: within the artificial domains which we have already constructed and linked back into society, the goal is to ensure that the machine’s objective function takes into account whatever democratic/human values we want to prioritize. Perfect alignment is impossible, but with blunt instructions we can insist on alignment on the handful of dimensions we think are most important.

The collision of 250 year-old electoral institutions with contemporary technology and culture has rendered democracy itself artificial. Horse-race media coverage, scientific polling, statistical prediction, deregulated campaign finance and A/B tested campaigning – these technologies of the artificial have come to stand in for democracy. But democracy is a process that requires humans in the loop—for it to function well, it requires that humans be the loop—which has been rendered ineffective because of the explosion of the artificial.

Democratic freedom must be rebuilt, starting from the small and expanding outward. John Dewey’s criticism is more relevant than ever: “we acted as if our democracy... perpetuated itself automatically; as if our ancestors had succeeded in setting up a machine that solved the problem of perpetual motion in politics... Democracy is...faith in the capacity of human beings for intelligent judgment and action if proper conditions are furnished.”

Concerns over citizens’ intelligent judgment have accelerated a technocratic/populist divide in our political culture. The technocratic solution is to constrain citizens’ choices, lest they make the wrong one. The populist solution is to deny and demonize the very concept of intelligent judgment.

But the fundamental problem is that our increasingly artificial world does not furnish human beings with the proper conditions. Democratic freedom is a creative freedom, the freedom of integral, embodied human beings interacting within communities, rather than “dividuals” fragmenting themselves into artificial environments.

We must reject the narrative that people or societies must feed ever-more of themselves into the whirlpool of the artificial to remain “competitive.” The more we optimize for metrics in artificial realms, the farther these realms drift from human reality. Populist politics, climate change and falling birthrates demonstrate the fragility of societies that have become too narrowly optimized.

We must instead recommit ourselves to each other – to reaffirm our faith

in democracy as a way of collective problem-solving. Each of us has to work towards being worthy of that faith, and to construct small pockets of democratic human activity to expand outwards, rather than letting ourselves be dragged apart into the various artificial whirlpools which have adopted the mantle of progress.

(This the first in a series of posts that aim at redescribing the present. Next week I will discuss the inversion of the business cliche that you should aim to sell shovels during a gold rush.)

Books that inspired this essay

Dan Davies. The Unaccountability Machine: Why Big Systems Make Terrible

Decisions - and How The World Lost its Mind. Profile Books, 2024.

Gilles Deleuze. Postscript on the societies of control. 1992.

John Dewey. Creative democracy-the task before us. The Philosopher of the

Common Man/GP Putnam’s Sons, 1940.

Marion Fourcade and Kieran Healy. The ordinal society. Harvard University

Press, 2024.

Mary L Gray and Siddharth Suri. Ghost work: How to stop Silicon Valley

from building a new global underclass. Eamon Dolan Books, 2019.

Eitan D Hersh. Hacking the electorate: How campaigns perceive voters.

Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Yuk Hui. The question concerning technology in China: An essay in cosmotechnics, volume 3. mit Press, 2019.

Kevin Munger. The YouTube Apparatus. Cambridge University Press, 2024.

Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor. AI Snake Oil: What Artificial Intelligence Can Do, What It Can’t, and How to Tell the Difference. Princeton

University Press, 2024.

Safiya Umoja Noble. Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce

racism. In Algorithms of oppression. New York university press, 2018.

Matteo Pasquinelli. The eye of the master: A social history of artificial

intelligence. Verso Books, 2023.

Herbert A Simon. The sciences of the artificial. The MIT Press, 1969.

Dennis Yi Tenen. Literary theory for robots: How computers learned to write.

WW Norton, Incorporated, 2024.

Subscribe to Never Met a Science

Political Communication, Social Science Methodology, and how the internet intersects each

This is beautifully framed; I love your flipping of the script from trying to "humanize" artificial spaces to rehumanizing the spaces. But you write:

"When humans act within an artificial space, their intelligence is artificial—their operations are indistinguishable from the actions of other actors within the artificial space. Note that these aren’t arguments; they’re *definitions*."

Are you sure this is purely definitional, with no claim folded in? Doesn't the whirlpool effect lie on a continuum (however much it's increasing); aren't there ways humans can still plausibly distinguish themselves even within an artificial space, to varying degrees? What you describe sounds more like a progression toward some hypothetical vanishing point, than either fully artificial or not artificial.

Also, I love the whirlpool metaphor but am not entirely clear what exactly the whirlpool is doing. Are you emphasizing more its centrifugal qualities (either that it pulls apart each individual into lots of data points, or pulls different individuals apart from one another); or its centripetal qualities (that it funnels and sucks all our humanity into an increasingly concentrated space)?

a wonderful metaphor for it!