Discover more from Never Met a Science

Why Aren't There More Millennials in Congress?

Boomer Ballast and the Zero-Sum Nature of Political Power

There is a cliché about how Millennials are entitled due to a childhood of “participation trophies.” Baby Boomers who hold this view should recall that their entire generation won Time Magazine's Person of the Year Award…simply by being born.

“Omphalocentric & Secure. What makes the Man of the Year unique?”

Cushioned by unprecedented affluence and the welfare state, he has a sense of economic security unmatched in history. Granted an ever-lengthening adolescence and lifespan, he no longer feels the cold pressures of hunger and mortality that drove Mozart to compose an entire canon before death at 35; yet he, too, can be creative.

Reared in a prolonged period of world peace, he has a unique sense of control over his own destiny—barring the prospect of a year's combat in a brush-fire war. Science and the knowledge explosion have armed him with more tools to choose his life pattern than he can always use: physical and intellectual mobility, personal and financial opportunity, a vista of change accelerating in every direction. (Time 1967).

The POTY Award has evolved considerably over the past century, and while the periodical news magazine no longer possesses the clout it once did, this central feature is a useful standard to measure perceived influence across time. Even their gimmicky choices have generally held up; they selected “The Computer” in 1982 and “You” (for social media) in 2006.

In 1966, two years after the babies stopped Booming, they selected “The Inheritors” as the Man [sic] of the Year, referring to “the man—and woman—of 25 and under.” The article is also effusive in describing the bounty of the world “The Inheritors” were born into, and uncannily prescient on the cultural evolution to come. Entitled or not, Millennials are definitely not experiencing “economic security unmatched in history.”

The initial conditions that were clear to the Time editors back in 1965 can explain much of today’s gerontocracy, what I call “Boomer Ballast” in my forthcoming book Generation Gap: Why the Baby Boomers Still Dominate American Politics and Culture.

The book is finally about to forthcome — I’d be honored if you’d check it out, pre-orders ship as soon as May 1!

Today, The Inheritors have fully Inherited. The rest of this post traces the contours of this Inheritance in two arenas for which we have comprehensive data: academia and Congress. The initial conditions played out in very different ways depending on the institutional structure of each arena — and sometimes, we see that institutional structure is endogenous to Boomer Ballast, that the demographic advantages were strong enough to let the Boomers change the rules in their advantage.

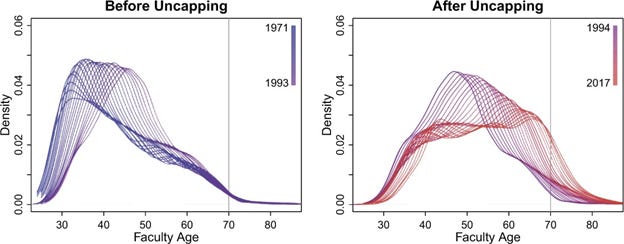

An article in the American Law and Economics Review by Daniel E Ho, Oluchi Mbonu and Anne McDonough provides the clearest example of Boomer Ballast I’ve ever encountered. Ho et al study directories of all American law school faculty from 1971–2017 and show that “uncapping” (prohibiting mandatory retirement) in 1994 had dramatic effects.

Focusing on the left panel of their Figure 1, before any policy change, we can see the ascendence of the Boomer generation in the early-middle stages of their life cycle. As the lines become more purple (as we move from 1971 to 1993) we can see the age distribution of faculty grow older. This trend continues in the purple part of the right panel, as the wave of Boomers ages.

The difference, in the right panel, is that we can see in red the years when law faculties began to be populated by people in their 70s and 80s.

The power of Boomer Ballast today is compounded, in the case of law professors, by advantages long in the past.

Law schools (and academia more generally) saw a dramatic expansion in the postwar era. The 1970s were the Golden Age of American academia, as university enrollment surged for demographic and Cold War-funding reasons. You can see this youth bubble in the bluest lines of the left panel above.

(This points to a constant bugbear of Boomer discourse: for many outcomes, it is really the people born between 1940 and 1955 who are outperforming the rest, a category that doesn’t match the official Census designation of the Baby Boomers as those born between 1946 and 1964.)

The composition of our elite institutions reflects our values as a society — and they highlight the zero-sum nature of power. While economic growth might be able to enrich everyone, there’s still an inelastic supply of jobs for professors or Members of Congress. And there’s never been a mandatory retirement age!

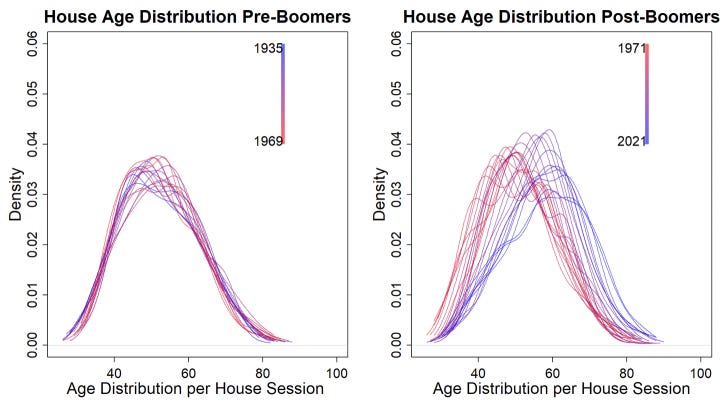

I asked Ho et al for the code they used for the beautiful graph above; they were kind enough to share it with me. So we have an apples-to-apples comparison between law faculty and the US House of Representatives!

Here, the two panels are divided at 1971 — the first year that a Boomer entered the House. The left panel serves as a “placebo test”: there are not any noteworthy trends among previous generations. Each of these seventeen Sessions of Congress had reasonably similar age profiles.

Not so in the right panel. As we move from red (1971) to blue (2021), we see the unmistakable wave of Boomer Ballast crashing through the House of Representatives. The past two Congresses, in the darkest blue, represent if anything an acceleration of Boomer power, age distributions well to the right of anything we’ve seen before.

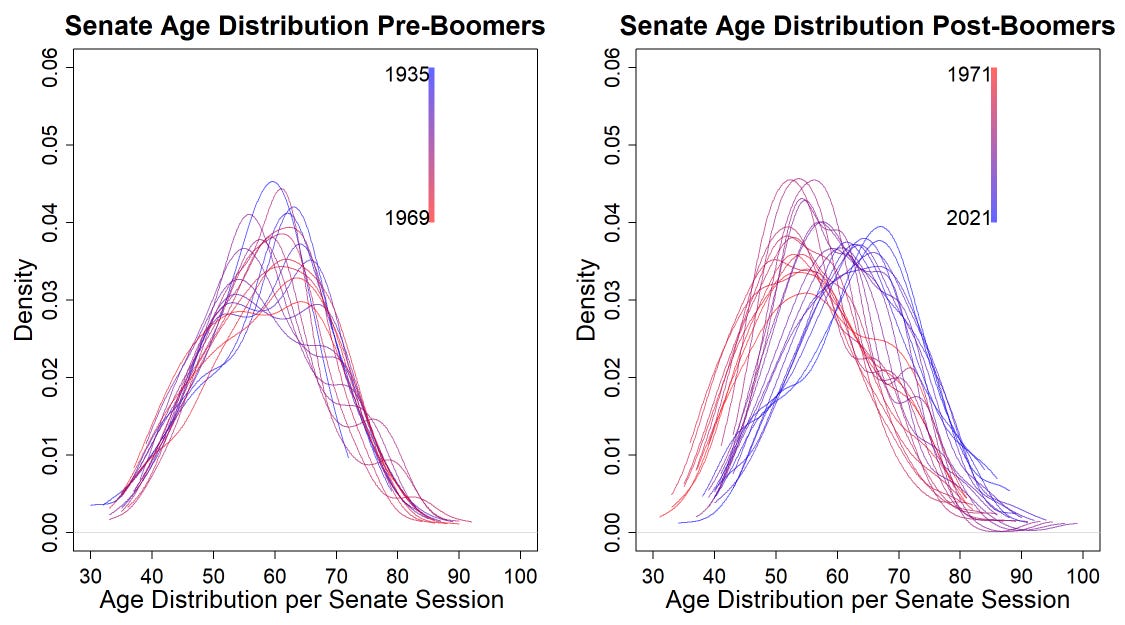

The trend for the Senate is even more dramatic. The graphs are somewhat noisier simply because there are fewer Senators, but just look at the right panel below:

The median age for a US Senator today is 65. We have become so used to the idea of the Senate as old and out-of-touch that the striking part of this graph, to me, are the red lines on the right side, the Senate of the 1970s. The demographic center of gravity included many Senators in their 30s and 40s — around four times as many Senators under 50 as we have today.

The flip side of Boomer Ballast in these zero-sum institutions is Millennial Missingness — the absence of younger generations from the seats of power. Imagine how different US politics would be if Jon Ossoff and AOC were part of an entire cohort of Millennial Members of Congress rather than the only people in the building who understand the generational housing crisis or how Instagram works.

Boomer Ballast is a much bigger problem in the United States than in demographically similar democracies in Western Europe because our outdated electoral institutions have locked us into a two-party system that controls every element of electoral politics. As I argue in more detail in the book, a defining question for the next decade of American politics is which of our two legacy parties will be the first to embrace younger generations.

The Democrats have a clear advantage: younger generations are far more likely to identify as Democrats, and this party owns many of the issues that are important for Millennials and Gen Z. However, the Democratic establishment has successfully defeated challeneges from the youth/left wing in the previous two Presidential primaries; this establishment is entrenched, well-organized and uninterested in ceding power.

The Republican advantage in the competition for the youth vote may be precisely the current weakness of the party establishment. Trump illustrated and exacerbated existing cleavages in both the social fabric and the ideological commitments of the GOP. The demonstrated "flexibility" with respect to long-standing Republican positions on free trade and military interventionism seems to have worked, and could a harbinger of future flexibility on issues that matter to younger generations.

In either case, the coming decade will extend the trend created by Boomer Ballast: our major institutions will fail to adapt even as the internet continues to revolutionize everything. The 2020s (and perhaps the early 2030s) will be a strange period of stagnation -- at some point punctuated by the window of opportunity that will come with the end of Boomer Ballast.