Susan Wojcicki Wants You To Think That YouTube's Algorithm is All-Powerful

Stop reifying tech's premises in seeking to critique it

In a working paper from last year, my co-author and I argued that public discourse about YouTube Politics was prematurely focused on a single affordance of the platform: the recommendation algorithm.

The algorithm tends to recommend alternative media (the theory goes), leading users down a “rabbit hole" into which they become trapped, watching countless hours of alternative media content and becoming hardened opponents of liberal democratic values and mainstream knowledge production institutions…

We think this theory is incomplete, and potentially misleading. And we think that it has rapidly gained a place in the center of the study of media and politics on YouTube because it implies an obvious policy solution—one which is flattering to the journalists and academics studying the phenomenon. If only Google (which owns YouTube) would accept lower pro fits by changing the algorithm governing the recommendation engine, the alternative media would diminish in power and we would regain our place as the gatekeepers of knowledge. This is wishful thinking that undersells the importance of YouTube politics as a whole.

Reviewers weren’t convinced, and we struggled to make a descriptive case that the “algorithmic perspective” was as ubiquitous as we perceived it to be.

(Indeed that paper needed a lot of work. I’m happy to report that a significantly modified version has just been published at the International Journal of Press/Politics)

On the topic of the centrality of the algorithm to the public discussion about YouTube, here’s the final of the recent NYT “Rabbit Hole” podcast:

“First, we know that the internet is largely being run by these sophisticated artificial intelligences that have tapped into our base impulses, our deepest desires, whether we would admit that or not. And they’ve used that information to show us a picture of reality that is hyperbolic and polarizing and entertaining and, essentially, distorted.

And now there are even more of these algorithms than ever before, and they are getting even smarter…

what we have is a situation where the A.I.s keep showing us this distorted reality. And then we keep paying attention to that. And in doing so, we are telling them that we would like to see more of this distorted reality.”

This is, IMO, the highest-profile and most in-depth mainstream account of YouTube politics to date, and it certainly centers the algorithm. But the algorithm isn’t creating the “distorted reality”: humans are!

As a counterpoint to the algorithmic perspective, I’d recommend the rest of the 8-episode podcast. The piece is competently and fairly reported, giving plenty of attention to all of the aspects of YouTube. And frankly I have no idea how the fixation on the algorithm survived that investigation.

The central narrative concerns Caleb, the young man who became far-right radicalized by YouTube and then came back from the brink. The origin story for Caleb is clear: he watched a video by S Molynew [sic] that the algorithm recommended him, then watched a bunch more, then saw that creator go on Joe Rogan’s podcast and got hooked on the larger alternative media ecosystem.

My question: how different would the recommendation algorithm have to have been to prevent Caleb’s radicalization?

Remember: people were exposed to new content before recommendation algorithms existed! This task used to be performed by humans, surfacing and recommending all kinds of media. Given that S Molynew was a popular YouTuber at the time, is it realistic that any recommendation system — algorithmic or not — would have prevented Caleb from ever seeing one of these videos? That world sounds radically removed from the one in which we live.

Perhaps the algorithm matters because it keeps someone watching a certain type of content. This theory involves very little user agency, a completely passive person who doesn’t navigate away from videos they don’t actually want to watch. And think about other “recommendation algorithms.”

Cable News’s recommendation algorithm is just to run one show after another, day on day. Holding the supply of YouTube Politics constant, how different would Caleb’s experience have been if YouTube’s algorithm was the same as Fox News’? Or alternatively, if after watching Molynew once he’d just binged all of his videos (maybe sorting by view count)? Not very different, I’d wager!

YouTube would still be a revolutionary new technology and a locus for political discussion under a variety of different recommendation algorithms, and that both scholars and activists are better off thinking about YouTube from the lens of supply and demand.

For example, from my paper with Joe:

Many people spend hours a day in contexts in which watching videos is simply easier than reading. Many people spend hours a day driving a truck or another vehicle, and they obviously cannot read while driving. The practice of white-collar workers performing their jobs while wearing headphones is increasingly accepted.

“Rabbit Hole” makes an identical observation:

“And then when I got my second job at the warehouse, we were actually allowed to listen earphones —…his YouTube watch time skyrockets even more. He’s actually spending all day —from sunup to sundown —online.”

There’s no easy policy solution here. I don’t think we can understand YouTube politics without understanding the larger techno-social context. YouTube meant exponential growth in the production of audio/visual political media—easily the largest such growth in history.

People love videos; there’s now videos about literally everything; and more people have the opportunity/technology to spend more of their time watching videos.

That’s what most important about YouTube. The algorithm is an efficient way to match supply and demand, and it definitely accelerates certain trends, but the demand is already there.

There’s a role for content creators to shape that demand, of course. Caleb’s story makes it clear that he didn’t start out as a xenophobic gun-and-religion-clutcher just waiting for someone to come along and “tell the truth about feminism” or whatever; he was an alienated, lonely young man with a taste for alternative internet aesthetics. And the people who made videos that spoke to people like him happened (due to structural social and economic factors) to have a certain ideological bent.

The podcast then does a great job of what brought Caleb out of the far-right rabbit hole: more, better YouTube videos. Specifically, people like Destiny and Contrapoints who understand alternative internet aesthetics and make videos from a broadly left-wing perspective. Caleb watches some of their content and begins to see the flaws in his recently-developed far-right worldview.

For a period from around 2013 to 2017 (based on the best descriptive data I have—-I certainly wish we had more!), there was a ton of alternative internet aesthetic, far-right politics content on English-language YouTube, and vanishingly little left-wing content. So if the algorithm determined that someone was interested in politics and not the Boomer-branded Fox News clips or Gen X-branded Jon Oliver clips, the recommendations were inevitably going to be to a certain type of content.

For activists, then, my recommendation is that you try to win. The technological game has changed, and there’s only so much to be done by abandoning the field of play and spending all your energy working the refs. De-platforming seems to work….in the short run. But in the long run, the capacity to produce and transmit videos is not going away.

Furthermore, from an industry-oversight perspective, amplifying narratives about tech companies’ omnipotent products is exactly wrong.

In Rabbit Hole, Roose goes to interview YouTube CEO Susan Wojcicki. Roose is discussing the relative role of humans and the algorithm (“then humans come in and sort of tinker with it to produce different results. Do you feel like when—”) when Wojcicki interrupts him to say:

Well, hopefully we do more than tinker. We have a lot of advanced technology, and we work very scientifically to make sure we do it right.

She can’t let even a slight minimization of their omnipotent technology slide; she goes out of her way to correct an offhand comment.

Given that the CEO of YouTube is committed to centering the power of the “very scientific advanced technology” behind the recommendation algorithm…why are anti-tech activists saying the same thing?

The story of Facebook’s ad targeting is similar. Facebook is deeply, deeply committed to the fact that their data allows advertisers to generate larger effects by targeting their ads. Many criticisms of Facebook take this premise for granted, usually in the service of calling for government intervention as the only sufficient counterforce.

We don’t yet have effective online platform regulation, but the knowledge actors nominally hoping to hold these megacorps in check have made damn sure that the public is aware of their technological omnipotence.

Dave Karpf makes broadly similar points in his fantastic article “On Digital Disinformation and Democratic Myths.” The whole article is worth reading, but his critique of the public conversation about “digital propaganda wizards” sharply parallels my view of the public conversation about “algorithms.”:

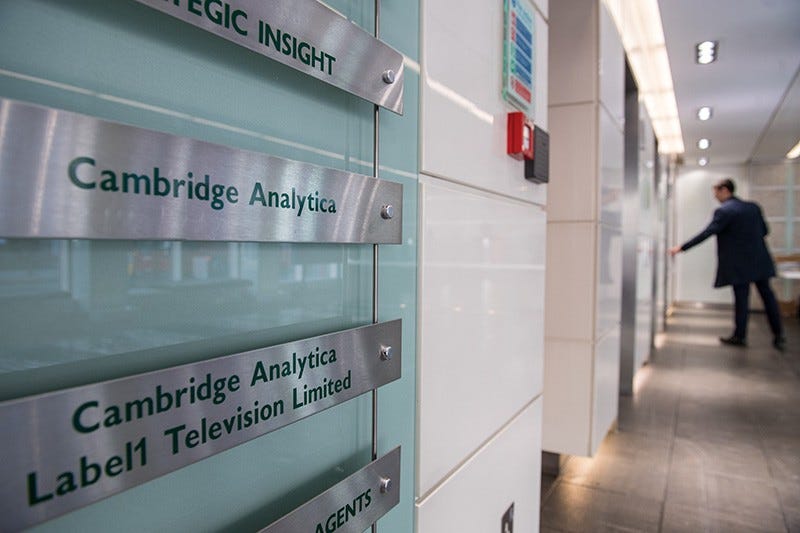

A story of digital wizards—an emerging managerial class of data scientists who are capable of producing near-omniscient insights into public behavior…

But [this story] has little basis in reality. Simply put, we live in a world without wizards. It is comforting to believe that we arrived at this unlikely presidency because Donald Trump hired the right shadowy cabal…

That would mean Democrats (or other Republicans) could counter his advances in digital propaganda with advances of their own, or that we could regulate our way out of this psychometric arms race. It is a story with clear villains, clear plans, and precise strategies that might very well be foiled next time around. It is a story that keeps being told, because it is so easy to tell.

But we pay a price for the telling and retelling of this story. The problem is that the myth of the digital propaganda wizard is fundamentally at odds with the myth of the attentive public…

It is easy for researchers to contribute to the myth of the propaganda wizards. Cambridge Analytica was made famous by well-meaning people trying to raise an alarm about the company’s role in reactionary political networks. But I would urge my peers studying digital disinformation and propaganda to resist contributing to hype bubbles such as this one.

Karpf was vindicated last month, when the UK Information Commissioner said that the “methods that [Cambridge Analytica] was using were, in the main, well-recognised processes using commonly available technology.”

One final irony: immediately before this discussion was the introduction of TikTok. As I’ve argued previously, on TikTok, the algorithm is newly central. TikTok accelerates the cybernetic feedback between producer and consumer to unprecedented rates; combined with the mobile-centric video feed and the level and distribution of hardware (ubiquitous mobile phones and fast enough internet), TikTok in 2020 represents a qualitative advance in social media.

Just because something wasn’t true about YouTube in 2016 doesn’t mean it can never be true…social science is hard :(