Discover more from Never Met a Science

The temporality of writing for the web has been accelerating; in contrast to the “golden age” of blogging, it feels odd to try and have a debate across multiple weeks when Twitter discussions are mostly finished with days if not minutes.

But I wanted to discuss a few recent posts by Economists about the pathologies of their institutions, some of which were in response to my last post (Wither, Economics), others just part of the zeitgeist. Perhaps the end of the academic year is a natural time for meta-academic reflections (here at Never Met a Science, of course, it’s always time for meta-academic reflections!).

First: these posts are in broad agreement with my criticism of the mis-allocation of rigor in Econ academic publishing.

But they disagree with my claim that Econ has too much power, prestige and human capital inputs; or rather, they don’t think along these lines much at all. The point of this blog—what I think should be the goal of all social scientists—is to increase the aggregate production of social science knowledge.

The Econ reformers, to their credit, are at least thinking about how to improve institutional incentives and practice; the modal Economist is still just cynically playing the game, having sunk too much of their self-worth into winning that game even as it becomes transparently stupid.

Evergreen cartoon from NYT

But still, these reformers are blinkered by the culture of Economics Exceptionalism. As usual, there is little to no awareness of Econ as one of several potentially complementary social sciences, no comparative discussion of the evolution of institutions in different disciplines that might illuminate useful interventions.

David Hugh-Jones kindly responded to my initial article with a post titled “Yeah, we’re imperialist.” Please read the whole post — but this is the part I care most about:

we’re writing good papers in other people’s disciplines, and the people in those disciplines lack the skills to challenge them. And this is our problem? Not theirs?

If I had attempted a straw man argument for Econ imperialism, I don’t think I could have come up with anything this incurious and self-satisfied. To repeat:

Broader efforts to reform social science practice cannot succeed without cracking open the sclerotic, insular discipline of Economics.

Matt Clancy, whose blog I’ve long enjoyed reading, cares deeply about getting better at producing knowledge. He provides a thoughtful discussion of the industrial organization of Economics:

We both seem to agree these methods produce high quality "units of knowledge." It's true that they require enormous effort to pull off, reducing the number of studies, but I think the benefits of all that work outweigh the costs. In a sense, instead of a half dozen papers tackling the same research question, in economics you end up with one super paper that tries to do everything those half dozen papers would have done, bundled together. Most of that work shows up as 50 pages of robustness checks (including the emerging practice of trying to do literally every defensible specification and data set). If there's a fixed cost to starting a project, gathering the data, and getting familiar with it, then it's lower cost to have one team do all that work than spread it across 10 teams.

Now, the tradeoff is a group of 10 teams will provide a greater diversity of viewpoints, and they will face differing incentives, which will likely result in better knowledge when all is said and done. Maybe the first one has an incentive to p-hack in order to get published, but the second has an incentive to null-hack to overturn the published result? Maybe it balances out? But we won't necessarily get multiple takes on the question if it takes enormous work just to publish one result (for example, if you have to run a giant RCT before you can say anything). In that case, we'll only ever have one person publishing (so they can grab priority), so we might as well make them do a lot of checks to make sure their data is robust.

But I think even the excessive care taken with modern empirical economics papers is still not enough! They are a pain to read and write, but I think they ultimately produce better social science than many small studies without the same care given to design.

This is broadly in line with what I’ve written in “The Theory of the Academic Firm”: the organizational scaling-up is a rational consequence of (necessary) increases in standards of rigor and changes in the technology of production.

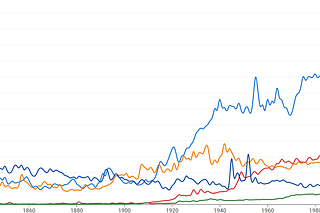

So I think the problem is that this new organizational reality must still be filtered through old institutions; worse, the institutional cart is in fact leading the scientific horse. Michael Makowski provides an excellent history of recent trends in Econ publishing, along with an easily-digestible summary (which again agrees with initial post):

To sum up: academic economics has more star researchers, managing larger teams producing more high-quality papers than there is space in the elite journals which have been forced to invent impossible acceptance criteria to produce the singular output that journal editors absolutely cannot shirk: rejections.

A further insight, on that sociological dimension that I think offers the greatest explanatory power for trends in social science:

[raising acceptance rates] would lower the value of every CV that already includes a Top-5 publication, but such is the struggle of every YIMBY vs NIMBY movement. Increasing the supply of elite journal publications won’t be a Pareto improvement (what is?), but it seems likely to me to be welfare improving.

This is the key problem. Tenured academics are too invested in the status quo distribution of status. Economists are fond of coldly rational arguments like the need to allow dictators to flee rather than force them to fight to the death; social science reform needs to work on an analogous “middle ground” exit strategy for our most august colleagues.

Makowski’s post draws on a valuable Twitter thread by Fabio Ghironi that hinges on the argument from opportunity costs:

That’s what I’m talking about. Increasing the aggregate production of social scientific knowledge, rather than reifying the received format of social science output.

Ghironi concludes by noting, accurately, that:

Editors and those who appoint them hold the keys.

Great news for these Econ reformers: you don’t have to invent institutional reforms from scratch! Other disciplines exist, with other institutional arrangements and debates, from which you can learn!

I humbly submit the Journal of Quantitative Description: Digital Media as one such case for comparative institutional analysis.

From the JQD:DM’s introductory “manifesto” (and inspired by our own experience with the pros and cons of the institutional arrangements of Poli Sci, Comm and CS):

Submission begins with a brief LOI to the editors that must address specific questions we pose to authors, available on the journal website. We anticipate a higher-than-average “desk reject” rate at this stage given JQD:DM’s circumscribed methodological and substantive purview. Sometimes, evaluating the LOI will be an iterative process as both the submitting authors and editors work through what an appropriate submission would look like given the proposed research questions and data. By design, many high-quality ideas will not ultimately meet our criteria for submitting a full manuscript for review.

This means that an unusually high percentage of papers that we send out for review will be accepted for publication. Today, so-called “top” journals retain their prestige by conspicuously consuming the time and energy of both authors and reviewers, using their market power to create artificial scarcity through plummeting acceptance rates. This practice is blatantly unscientific and potentially unethical. When we send an article out for review, we affirm that it is within the scope of JQD:DM and that it passes our baseline requirements for scientific validity. The task of the reviewers is thus constrained to evaluating the quality of the methodological implementation and the theoretical contribution. To be sure, there is no guarantee of publication just because an LOI is accepted, but it does guarantee that the paper will not be rejected due to “lack of fit.”

We will report the results of this “experiment” as soon as possible, but we’re pleased with how it is working so far.

The final “meta-Econ” post comes from Tyler Cowen (published on the same day as my previous piece). While in broad agreement with the diagnosis of increasing rigor in journal publishing, Cowen makes an argument that relies on the temporality of writing for the web.

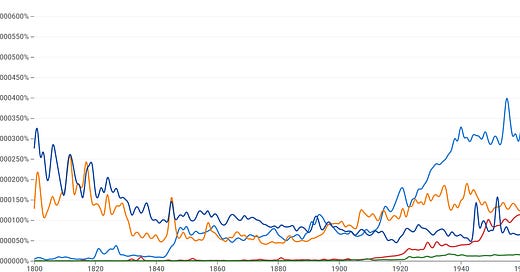

The emergence of #EconTwitter — with extremely low barriers to entry — has replaced some of the functions of scholarly publication.

an earlier culture of “debate through books” has been replaced by a new culture of “debate through tweets.” This is not necessarily progress…By demanding so much rigor in academic research, they’ve created an environment in which most of the economics people actually see is less rigorous.

I strongly agree that social scientists should think hard about the role Twitter discourse plays in the circulation of the knowledge we produce, within and without academia. Twitter is a genuinely important part of the knowledge production process, and I’d prefer it if people took it either more or less seriously.

And taking temporality seriously — treating “temporal validity” as one of the major dimensions on which papers can be better or worse — means acknowledge that there is no such thing as a “perfect paper,” to use Cowen’s phrase. With a zero temporal “discount rate,” a paper that takes 8 years to publish and and includes only 17 robustness checks is in fact better than a paper that takes 4 years to publish but only has 2 robustness checks. Given growing competition for a fixed number of hallowed slots in elite journals, the dynamic selects for longer, slower papers.

Acknowledging the reality of the social scientist in time presents one angle for institutional reform: lowering the status of these “perfect papers” by criticizing them for being dated. Raising the status of other forms of knowledge production—faster and thus more relevant—is one way out of the current wasteful rigor-signaling bonfire of human capital.

Subscribe to Never Met a Science

Political Communication, Social Science Methodology, and how the internet intersects each