This blog is about two things: (1) the radical changes wrought by modern communication technology; and (2) the inability of the epistemic technologies of the written word to understand point (1).

I find this dialectical tension to be generative, but I can see how readers looking for answers might find it unsatisfying.

A recent paper in Nature, titled “Online images amplify gender bias,” makes the point in a more familiar format. Consider the first full clause of the first sentence of the abstract:

“Each year, people spend less time reading and more time viewing images”

BOOM. Footnoted: “Time spent reading. American Academy of the Arts and Sciences https://www.amacad.org/humanities-indicators/public-life/time-spent-reading (2019).”

I’ve frequently claimed that the age of reading and writing are over, with varying forms of evidence ranging from the political, the phenomenological and the Pew Research Center. I don’t think I’ve ever convinced anyone -- some people (typically young, or frequently in contact with young people) already feel it to be true, and the rest won’t change their mind after reading a blog post. This is the contradiction of points (1) and (2). And yet Guilbeault et al (2024) establishes the relevant claim as a social scientific fact of the highest order.

How is this done? The introductory section of a social science paper in Nature is an odd medium. The argumentation has to range from the expansive to the specific, and the specificity has to cover a variety of spaces within the expansive argument -- all exhaustively footnoted.

If you squint, this procedure becomes absurd. The clause in the abstract becomes “the time they spend producing and viewing images continues to rise[2,4]” in the body of the text.

Footnote 2 refers to a CS paper from 2013. Footnote 4, to a technical report from something called Bond Capital, in 2019.

Is this, in fact, evidence for the claim that “the time Americans spend producing and viewing images continues to rise”? What if this paper were to have been published in 2026? 2030?

And how does the fact that the main data analyzed in this paper were collected in August 2020 change things?

Of course, if you accept my premise (2), the literal content of the text doesn’t matter. The paper is a beautiful example of the contradiction inherent in techno-logos: we spend more time creating and consuming images, and less time producing and consuming texts. The evidence for this, recursively, does not reside in the text but in the images.

In the Flusserian framework, these are technical images. Images in fact predate texts; texts were invented because we stopped believing in images and we needed texts to explain those images. But the images in the pdf are not traditional images. Both the images under study and the statistical curves produced by the authors are technical images. These technical images are a cause and consequence of the fact that we no longer believe in text, and that we have invented technical images to explain those texts.

But let’s stay concrete! Guilbeault et al (2024) was published in Nature; what would the response be to me writing on my blog that:

“The time Americans spend producing and viewing images continues to rise. How do we know this? Zhang & Rui (2013) find that in the year 2012 there were billions of image searches conducted by Google, but in 2008, there were only a few thousand.”

The amount of evidence contained in the text is obviously insufficient to the claim — even if the information in the text is identical in the blog post and the Nature paper. The reason we believe the text in the Nature paper is because of the technical images in the pdf — these images point not to the world but to data, the true repository of knowledge today.

It bears mentioning that gender bias, the nominal focus of the paper, is a complete red herring. Obviously the argument is more compelling with an empirical demonstration, and it makes sense that the example would be something that people care about, that directly impacts their lives. But I fear that the focus on this issue obscures the argument itself.

The important part of this paper is the formal, large-scale demonstration that the mediums of text and image have different information-theoretic properties. We can try to demonstrate this empirically through small-scale experiments—indeed, I have done just this—but these demonstrations are always with respect to a given outcome, and have somehow not been convincingly synthesized. Alternatively, we can try phenomenology, to get people to experience these different mediums and reflect on this experiencing, to just THINK about what texts and images do—but that's not scientific (Naturetific? Haha. I’m not envious at all.)

Or how about using language seriously? The claim here is that images provide more context than does text. That is, there is more extra-textual information in images than in text. What would it mean for this to be false? We literally can’t even think it false without linguistic contortion.

Another problem with the focus on the empirical case of gender discrimination is that the specifics of this case might change, but that our fundamental conclusion should not change. For example, the primary source of data for both the observational and experimental analysis is Google.

And Google is currently paying a whole lot of attention to the relationship between text, image and the representation of identity. There’s essentially zero chance you’re reading this without having heard about last week’s Gemini controversy, but just in case.

The point of this controversy is that images convey contextual information that is not present in text. This is not a problem that can be solved with RLHF fine-tuning or changing the composition of the training set; it’s a communicological fact.

It would not be (that) difficult for Google to reverse-engineer the specific analyses conducted in the Nature paper; the distribution of races and genders demonstrated for each occupation could be made to statistically match those in the Census, for example. Would this lead us to change our inference, to instead conclude that images and text contain the same amount of contextual information? No, of course not.

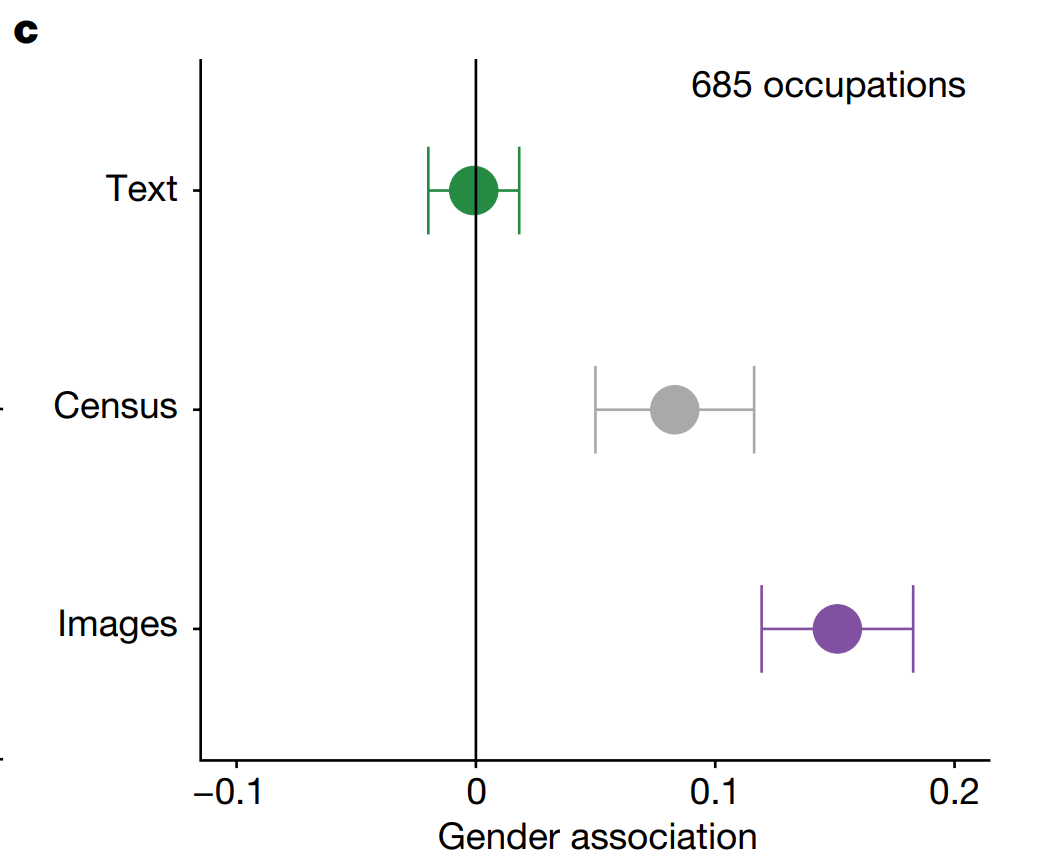

Returning to the paper, let’s ponder how Figure 2 shows that *the Census* has more “bias” in terms of gendered occupations than does the collection of texts. What on earth does this mean?

It means that our conception of “bias” is based on deviation from the textual, mathematical, linear, logical. This medium of communication and the associated habits of mind are very good at handling bias. But there are drawbacks. This medium is poorly equipped to communicate scale, change, and variation.

Images then necessarily introduce bias. A single image of a “philosopher” will necessarily be biased compared to the single word “philosopher.” One way in which it might be biased is gender; the word philosopher is not gendered, but most realistic images of people are gendered — not essentially or transcendently, but in practice gender is a pretty big part of self-presentation. But another way it might be biased is temporally. The word “philosopher” transcends time, but any realistic image of a philosopher would place them *in time*. The image would necessarily be biased compared to the word because images are better at conveying variety than at avoiding bias.

Here it become essential to understand what Flusser means by technical images as distinct from traditional images. These images “produced” by Google search or produced by Google Gemini are not images of the world; they are images of DATA. As are the images like Figure 2c above. These technical images are thus better than texts at conveying scope — and if extended to the third or fourth dimension, can be used to effectively convey dynamism as well. But just like traditional images, they are necessarily biased compared to text.

My hope, here, is to forestall a cottage industry of extending Guilbeault et al (2024) to every conceivable dimension of human communication. It is of course valuable to audit any given algorithm that has power to make decisions at societal scale — indeed I think that we are obligated to do so, and to generate time series data to see how these specific important algorithms are behaving over time — but the more fundamental point is that different modalities (“codes,” in Flusser’s framework) convey different kinds and amounts of information.

Simply by thinking about what these modalities do and tracking their empirical rise and fall in different areas of human endeavor, we can develop a much more robust understanding what information technology is doing to us — and we can decide if we’d rather it do something else.

Have you ever read "Discourse, Figure"? It's a truly insane, but also inspiring book. (Try "Veduta" in the middle).

Lyotard talks about the change of the relationship between discourse and figure. They define each other negatively, or even like: Image is somehow "bigger" than text, but is also defined by text, because our only access to the image's content is through the "script"; there's no way to decode/understand the image if you don't perceive it in the relationship to the text, very likely a negative relationship for sure.

I find this approach of considering their relationship, their balance over time as a rich view. I think contemporary texts, written by or with the eye to the recommender engines (which operate on continuous values), are moving to the "image" territory, just as the prompt-generated, or formal-current-tiktok-style produced images get closer to the text. (Meme, an image with a text, has as little extra textual information as possible).

I'm wondering about the statement that there is more extra-textual information in an image than in a text. I am not clear about what you mean by "text".