GPT-3: Informational Hyper-Inflation

The paradox of communication technology

Many of my techie friends and internet acquaintances have been obsessing over a new AI model: GPT-3.

I’ll leave to summary to one of the OGs of the field, Gwern:

GPT-3, announced by OpenAI in May 2020, is the largest neural network ever trained, by over an order of magnitude. Trained on Internet text data, it is the successor to GPT-2, which surprised everyone by its natural language understanding & generation ability. [GPT-3 is] learning more facts & text than GPT-2, but qualitatively distinct & surprising in showing meta-learning: while GPT-2 learned how to do common natural language tasks like text summarization, GPT-3 instead learned how to follow directions and learn new tasks from a few examples. (As a result, GPT-3 outputs & interaction are more fascinating & human-like than GPT-2.)

In practice, this means that arbitrarily large amounts of novel text about any topic can be produced ex nihilo. Take the pre-trained models, feed in a bunch of text from the target context, and let’er rip.

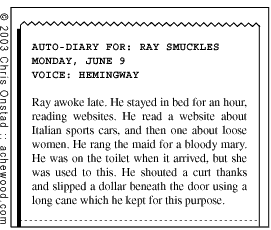

This could be used to create a chatbot trained on the transcript of every episode of Friends (inane) or to take a simple story and re-write in the style of a given author (insanely tight). One of my favorite webcomics presented the latter as sci-fi back in 2003:

Gwern uses GPT-3 to make it real, in 2020. (Here, Hemingway does the Harry Potter series):

"It was a cold day on Privet Drive. A child cried. Harry felt nothing. He was dryer than dust. He had been silent too long. He had not felt love. He had scarcely felt hate. Yet the Dementor’s Kiss killed nothing. Death didn’t leave him less dead than he had been a second before. It wasn’t about living or dying really. It wasn’t about death. It was about the Dark Lord, his creator, his engenderer. He was not resurrected. He was created again. He was whole again in the courtyard of Malfoy Manor."

Human communication is social. From any perspective — game theoretic, anthropological, psychological — the main purpose of communication is to enable and manage complex social arrangements. IRL or mediated, when we receive communication, our primary aim is to learn about what other humans do, think and desire.

This is also true of social media; Political Scientists can sometimes lose sight of this, so I repeatedly invoke Jaime Settle’s insight that political interaction on Facebook is “first and foremost a social behavior.”

One implicit assumption about communication is that it does in fact contain social information. One way to think about this “social information" is how much human intentionality was involved in the process that led your senses to receive that communication; that is, how much human time, thought or effort it required.

The ratio of intentionality contained at different stages in this process has shifted with technology. If the communication is face-to-face, there’s direct observation of the intentionality of the interlocutor, and structurally, there’s social information encoded in the fact that you’re interacting in the first place.

With broadcast tv, there’s the representation of the human intentionality, the structural information, and common knowledge information that many other socially relevant humans are encountering the same media object.

Some of these levels are radically obscured on social media, but the reason we love it is that it gives us information on human intentionality at scale. We can begin to infer entire social networks based on who likes and shares what. Consider the emergence of communities like “basketball Twitter” or “#polisci Twitter,” where posters learn to anticipate the response from their community based on intuitions that emerge from the process of observing other posters.

GPT-3 is a communication revolution that threatens to eliminate the possibility of information about the original human intentionality behind a given text post.

The essence of a lot of “trolling” is to exert minimal effort for maximal response — to inflict costs on others for caring more about something than you do. A classic technique is the “copypasta”: paste a lengthy text and get someone to believe that it was freshly written, that it is evidence of human intentionality at the margin of a given interaction. This is a “weapon of the geek,” per anthropologist Biella Coleman, asymmetric warfare by the traditionally weak enabled by their digital savvy. But the range of applications for a given copypasta is limited. GPT-3 blows past these limits; the pasta it creates isn’t stale, but neither is it truly fresh: pasta simulacrumbs.

MIT Tech Review reports on a Reddit bot posting the output of GPT-3 on active text threads. These threads observed by (potentially many) other pseudonymous Redditors, but the premise is that the text of each post is the result of some marginal human intentionality.

“Responding to a request for advice from Redditors who said they had had suicidal thoughts in the past, the bot replied: “I think the thing that helped me most was probably my parents. I had a very good relationship with them and they were always there to support me no matter what happened. There have been numerous times in my life where I felt like killing myself but because of them, I never did it.” The response was upvoted 157 times.”

This is a sensational example, and justifiably so. But I’m once again frustrated by the narrow journalistic framing of an epochal technology: the fear is that careless use of GPT-3 could “cause harm.” We can easily imagine the next story focused on the issue of “algorithmically generated Fake News,” more guaranteed journalist- and audience-bait.

This is literally true, but the reality is more troubling: without some kind of friction (like reputation, transmission delays/limits, or captchas), GPT-3 renders textual digital communication impossible. Not an explosion of Fake News but the impossibility of Real News.

The rate of change is terrifying. How soon will we have GPT-Image? At present, a popular form of online disinformation is to upload an image from an older, unrelated protest or war zone and claim that it’s happening at an active one. An archive of images to cross-reference, or pictorial clues that point to the earlier location, can be used to debunk this misinfo. But what if there can be infinite, unreal images trained on previous, real images from that specific war zone or protest? Or unreal images that synthesize those real images with images of the combatants of the propagandists’ choice?

The presence of a photograph implies a photographer, but GPT-Image renders that moot.

People aren’t not gonna use this tech, but the only people paying serious attention to these developments are also deeply concerned about its implications.

Perhaps you’ve heard about the loony tech bros who are obsessed with AI, ignoring present political issues to think about some far-off technology. Regardless of whether your preferred eschatology involves building a godhead of silicone, the world is about to have to grapple with intelligence proliferation; the reality is that this AI is already here.

Servers running GPT-3, appropriately trained on a specific text domain (like Reddit’s Am I the Asshole forum) could trivially double or triple the total number of words uploaded to that forum. Tens of thousands of humans would be immediately become victims of what I call “information fraud”: consuming signals that purport to contain information about human intentionality when that information is in fact absent.

To use a concrete example more relevant to academics: GPT-3 immediately makes it trivial to produce a decent 10-page paper on any topic. The model is unlikely to provide a novel insight about, say, The Great Gatsby, but neither will it produce anything that can be detected with traditional plagiarism software.

Or think about product reviews on Amazon, restaurant reviews on Yelp, comments on the NYT Op-Ed page. All of this works because we assume human intentionality produced the text.

We live in an information economy; there are more possible applications for GPT-3 powered information fraud than I can imagine. But many of our systems rely on “information stability” in our signals; the specter of “infomational hyper-inflation” is haunting the web.

In the short run, this will entail the tech-savvy defrauding the not-so-much. In the absence of additional frictions, however, one equilibrium is all of our platforms dominated by bots chattering back and forth at each other, and post-human menagerie echoing back the last human intentionality we put into the system.