Attention is All You Need

Reading Expands Our Context Windows

One of my foundational theoretical commitments is that the technology of reading and writing is neither natural nor innocuous. Media theorists McLuhan, Postman, Ong and Flusser all agree on this point: the technology of writing is a necessary condition for the emerge of liberal/democratic/Enlightenment/rationalist culture; mass literacy and the proliferation of cheap books/newspapers is necessary for this culture to spread beyond the elite to the whole of society.

This was an expensive project. Universal high school requires a significant investment, both to pay the teachers/build the schools and in terms of the opportunity cost to young people. Up until the end of the 20th century, the bargain was worth it for all parties invovled. Young people might not have enjoyed learning to read, write 5-paragraph essays or identify the symbolism in Lord of the Flies, but it was broadly obvious that reading and writing were necessary to navigate society and to consume the overwhelming majority of media.

And it’s equally obvious to today’s young people that this is no longer the case, that they will not need to spend all this time and effort learning to read long texts in order to communicate. They are, after all, communicating all the time, online, without essentially zero formal instruction on how to do so. Just as children learn to talk just by being around people talking, they learn to communicate online just by doing so. In this way, digital culture clearly resonates with Ong’s conception of “secondary orality,” as having far more in common with pre-literate “primary oral culture” than with the literary culture rapidly collapsing, faster with each new generation.

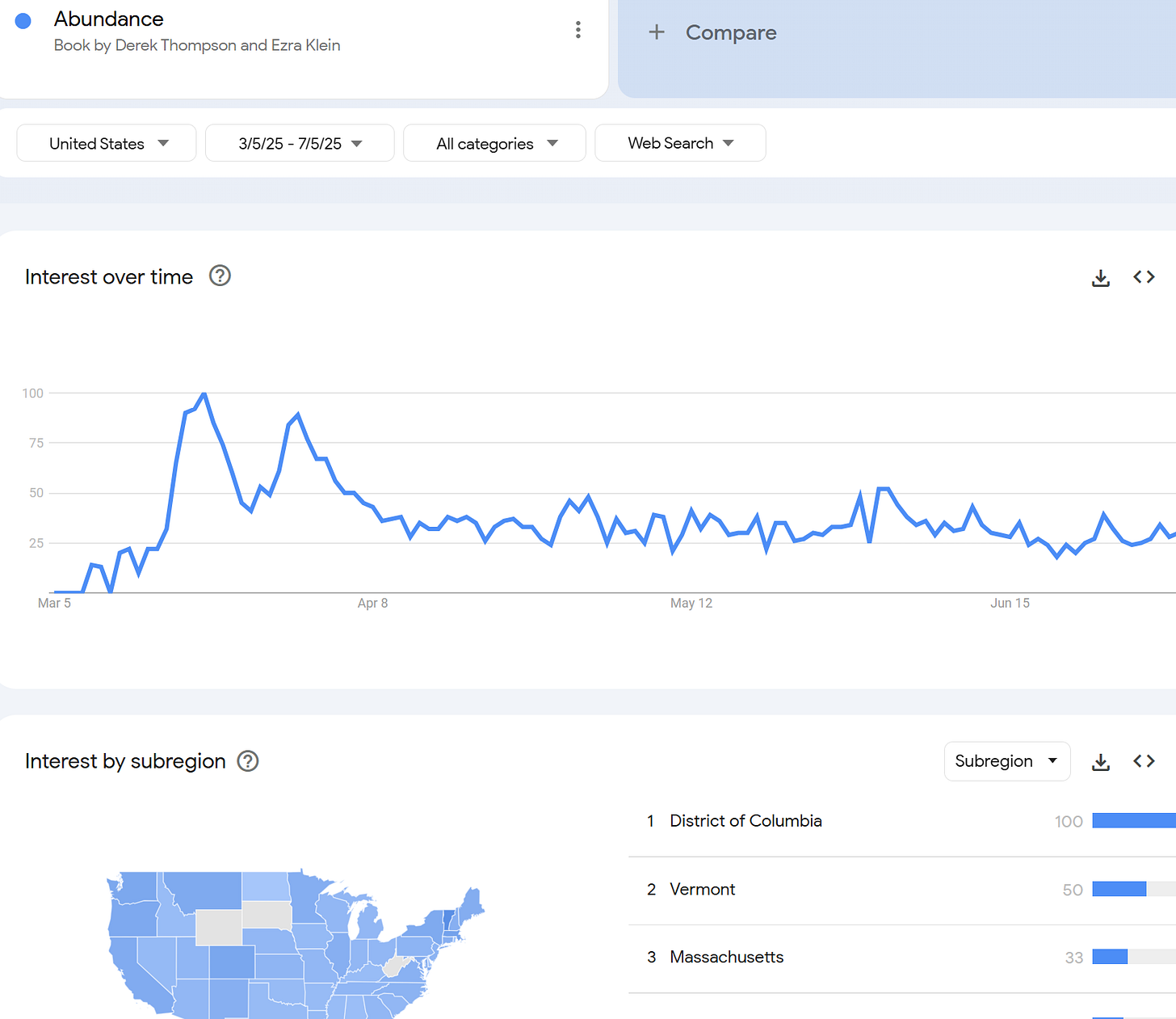

This collapse is increasingly obvious; recent high-profile midbrow examples include Chris Hayes’ book (best experienced through the medium of an Ezra Klein podcast) and Derek Thompson’s report on the end of reading:

“What do you mean you don’t read books?” And they go, “Well, we just studied Animal Farm in our class, and we read excerpts of Animal Farm and watched some YouTube videos about it.” And I basically lose my mind. I’m like, Animal Farm is a children’s parable. It’s like 90 pages long.

But we still don’t know how bad things really are — for two reasons:

Literary culture still exists. People read and write things; motivated teenagers might find it easier than ever to find long-form text suited to their taste. But the medium of communication is a stronger filter bubble than any algorithm. I am literally never going to watch a YouTube video or Twitch stream if I can help it; as someone committed to literary culture, I detest them. Because I’m a media scholar I’ve forced myself to overcome this revulsion, to for example write a book about YouTube, but otherwise I would be completely unaware of the gravity of the cultural difference.

Our political culture is unable to comprehend the depth of the problem posed by changing media technology. The latter point is exemplified by these same liberal progressives Klein and Thompson writing a political manifesto for premised on supply-side innovation and technological progress — which at no point addresses the decline in literary culture which they have both recently podcasted about.

This problem dates back to Plato, as many people who are critical of media technological determinism are quick to point out, and the argument in the Phaedra that this new technology of writing will cause us to lose our capacity for memory. And yet, the critic says, we can still remember things, so maybe writing doesn’t do anything to us at all!

This is put somewhat glibly, but to understand the problem with this argument, we need to appreciate that we don’t have any ground to stand on when it comes to understanding humanity and our relationship to media technology. This is Flusser's idea of groundlessness, the fact that we are no longer grounded as a civilization because of our changing media technology. We have no stable point from which to evaluate how we experience the world and how other humans in different societies with different mixtures of media technologies appreciate the world.

This means that it’s impossible to make evaluations of whether a change in media technology (or, if you like, progress in media technology) is going to have good or bad effects on us. What we can say is that it will change us. It will change who and what we are. Lacking a stable point to evaluate this from either a positivist descriptive angle or through a normative angle of how humans should be, we don’t have any ability to evaluate whether a given change is good or bad. It is simply a change. It re-writes the rules of good and bad.

The way this plays out in our current social cultural, political environment, is that conservatives raise some opposition to new media technology, because being conservatives, they like at least certain things about our current social, cultural matrix, and they are sensitive to potential changes in this environment. As a result, they raise this opposition to whatever new media technology comes along, and in dialectical opposition, of course, liberals react to this reaction, and come up with reasons why this new media technology isn’t such a big deal. Internet porn is an easy example.

In terms of issue salience, it’s simply not in keeping with contemporary progressive liberalism to think that new media technology is a big deal. Because they are dissatisfied in some ways with the sociocultural status quo, they are able to identify ways in which the new media technology might have positive effects on certain elements that they would like to see changed. They are resistant to the idea that media technology might have broader effects that might reshape our sociocultural matrix in ways that they cannot anticipate or even understand.

And so the key question for liberals is empirical. Do we think that the current type of change is large enough in magnitude that it represents a kind of rotation of our sociocultural matrix? Or do we think that it is the kind of thing that can be managed, that can be adapted, so that we can keep only the things that we like about a new technology, or at a minimum that we can do a utilitarian calculus and move forward as long as the benefits outweigh the explicitly defined harms?

My own position is, of course, that the decline of writing as a media technology absolutely represents a rotation of the matrix, that a utilitarian calculus is ridiculous, and that we cannot hope to get only the good parts without the bad.

I’ve written on this theme many times before; blogging is an exercise in saying the same thing over and over again. So let me try a new metaphor for the same message.

This rationalist tradition tends to reflect its proudest technological achievements back on the human condition. From the 1600s to the present, Western society has likened the body to a clockwork machine (inspired by mechanical clocks and automata), then to a steam engine (reflecting 19th-century ideas of energy, pressure, and fatigue), a brief detour towards the Jacquard Loom and weaving together strands of thought, followed by the nervous system as a telegraph network (mirroring telecommunication systems). Ever since the 1950s or so, the metaphor of the mind as a computer has been central to how we understand ourselves.

But the “computer” metaphor is getting stale. Media theorists have noticed this for a while, and have been busy updating it; I especially recommend K Allado-McDowell’s framework culminating in contemporary neural media.

My contribution comes from having just taught a PhD seminar in Computational Social Science methods, getting into some of the details of how the generative pre-trained transformer models undergirding today’s “AI” work.

There are four essential advances in the past decade that have transformed LLMs into the potentially world-changing technology they are today. The first is simple and well-understood: they have sucked up more and more training data, pirating “the whole internet” and as many books as they can get their hands on; Moore’s Law is probably slowing down but we still more processing power to throw at that data. Big computer better than small computer, so far the old metaphor works.

The second is similar, and can be understood through a parallel to the hard drive and RAM. The training data is the hard drive, a static repository of knowledge; RAM, the active memory applied to a task, is the context window, or how many words the LLM can hold in its memory at once. This is usually a tighter constraint than training data, computationally — just like hard drive capacities have grown faster than RAM, it’s less expensive to grow the size of the training set than to expand the context window.

The third advance is more discontinuous, and directly interacts with the context window: the Transformer (the T in ChatGPT) models that kicked off the new era did so by parallelizing the training process to include all of the words in the same context window at once.

The 2017 paper introducing Transformers was called “Attention is All You Need.” The metaphorical resonance between machines and humans is hard to overstate.

“Attention” here is means the amount of weight the model puts on each word in the context window. An essential advance for today’s extended, chat-based interactions with the models is their ability to “attend to” both the user’s inputs and their own previous outputs.

If you just want to optimize a static classifier or rapid stimulus-response model, you don’t need attention and long context windows; you can just feed it as much data as possible. The larger the context window, the more important attention becomes.

Analogically, we can understand the role of reading in human cognition. Paying attention to an extended narrative requires us to hold a lot in our head; tracing complicated historical accounts requires paying attion to many simultaneous forces.

In contrast, scrolling a feed means shortening our context window. Short-form video like on TikTok, Reels or Shorts makes our attention less important. We are turning ourselves into these simple stimulus-response algorithms—content zombies, as Sam Kriss describes with characteristic cruelty.

It’s now cliche to say that LLMs are replacing our capacity for cognition; cliches often contain some truth, but we can benefit by drilling into the technical mechanism by which this cognition is being outsourced. By abandoning the technology of longform reading and writing, we are shortening our context windows and thus weakening our capacity for attention. At the same time, LLMs advance by expanding their context windows and refining their capacity for attention (in the form of some hideously high-dimensional vector of weights).

Attention is all we need — and the lesson of media ecology is that it doesn’t come easy.

tl;dr?

Your breakdown of these four different LLM advances is very helpful. Have you seen Jac Mullen's new Substack, After Literacy? He recently kicked off a series of posts advancing the thesis that LLMs, coupled with our new communication infrastructure, is effectively externalizing attention in a way analogous to how writing externalized memory. The way he applies this seems very related to your fourth form of LLM innovation: the ability to attend to both itself and the user given the bigger context window. (Or was this the third? You only seemed to cover three).

It feels like you might have buried the lede just a tiny bit at the end (is there a special term for burying the final point not the lede?). If I understand correctly, what's key here is not simply that we have been shortening our context windows and weakening attentional capacities, but that only very recently LLMs began *replacing* our window as they expand their own - meaning some complex interaction between the distinctively human effects of letting our own context window decay, and the distinctively LLM effect of lengthening theirs in more algorithmic fashion. So one implication is that we increasingly outsource attention to the LLM, even more than what was already happening with media technology. But maybe also, this is much more than a matter of outsourcing tasks, or direct linear substitution of our attention with theirs?